Jeremy McGrath And The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Night In St. Louis

By

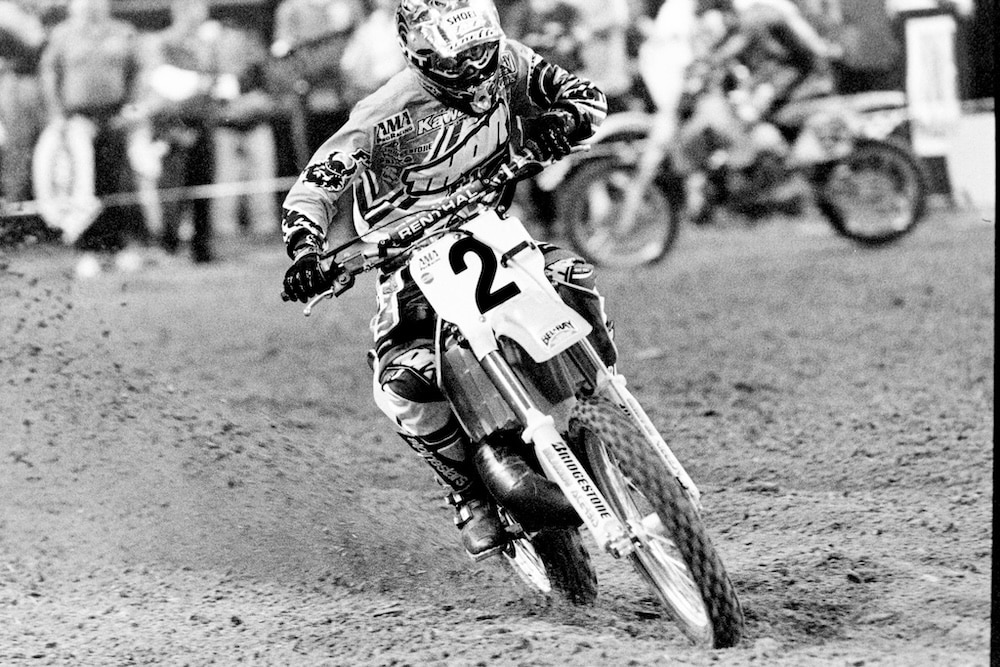

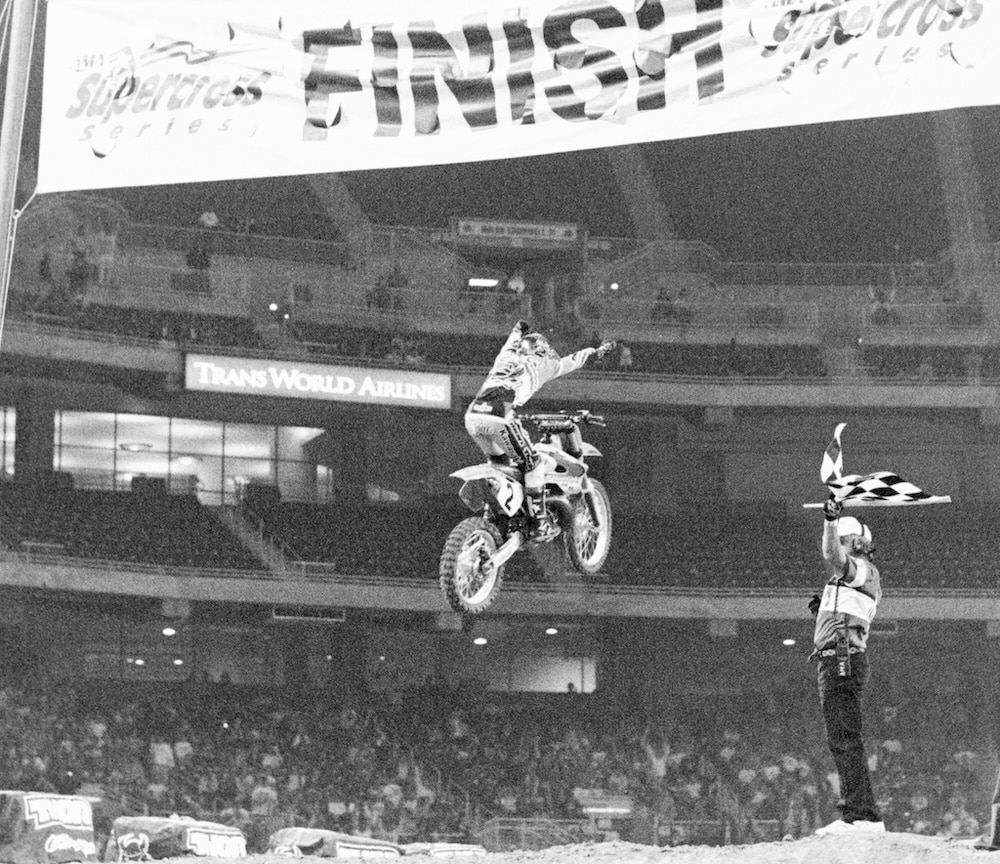

On April 27, 1996, Jeremy McGrath fell short of perfection and the rest of the world won’t let him forget it.

Skip Norfolk blew it. Decades later he repeats himself mantra-like in recounting one of the more sour memories in his career as McGrath’s race mechanic.

“I didn’t do my job…”

“I let the guy down…”

“I wasn’t able to…”

“I failed him.”

McGrath didn’t know about this burden Norfolk carried until long after retirement. He had no idea Skip blamed himself for the 1996 St. Louis Supercross loss, the only blemish in a season where McGrath won 14 out of 15 races, including a fourth consecutive championship. And he bristles at the first mention of being asked to discuss the race.

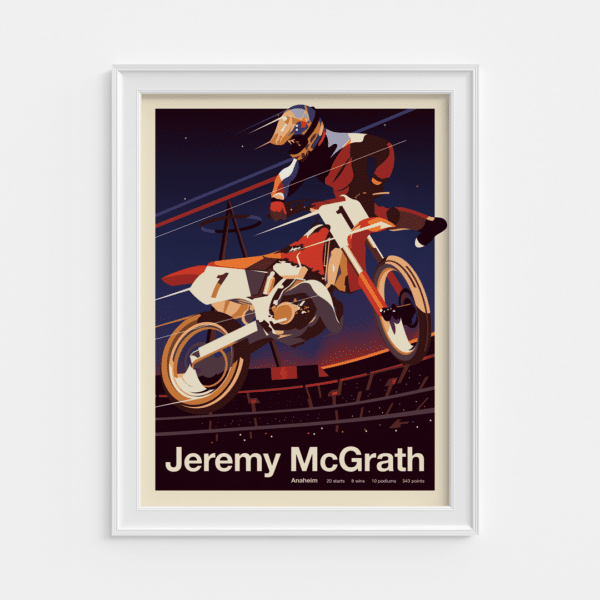

Although he’s most famous for his record seven championships and 72 main event wins, when the 1996 season comes up nobody asks him about how he dominated, or how he won Daytona for the first time, or led every lap in the wind and rain at Charlotte Motor Speedway. Or how he won the championship a full three races early, clinching at the Pontiac Silverdome.

It’s always about the night that he took [sigh] second place. The philosophical argument about 1996 is, what was more unusual, the fact that Jeremy McGrath had won the first 13 races or that there could be a night where he simply wasn’t the best rider?

“I made a career doing the things that people thought I couldn’t,” McGrath said. “I was fortunate to be good enough to where that type of race – where I got second –was a miserable race. That’s a weird thing to say.”

McGrath dominated the ’96 season but, like any sports streak, he caught some breaks. In Seattle he rebounded from a poor start and was passed by Damon Huffman three times for the lead. Attempting a fourth pass, Huffman stalled his bike and couldn’t catch McGrath again. In Indianapolis, Jeff Emig led comfortably at the halfway point and in an unforced error, washed out in a corner. ‘What if’ talk won’t change history but can be fun for discussion. What’s certain is that McGrath was not the best supercross racer on one night in St. Louis.

“So many things lined up wrong to go racing that day,” Norfolk says. None of the parties involved can offer a detail that specifically caused the outcome of this race, but in a season where nothing could go wrong for McGrath’s team, suddenly there was a series of minute circumstances that, in hindsight, collectively didn’t seem right. The first clue arose long before they arrived in St. Louis.

Skip Norfolk: “We Were Standing There Naked!”

The 1996 race was held at a new stadium, what was then called the Trans World Dome. It had only been open for five months and parts of it were still under construction. Two weeks prior to the race, AMA referee Duke Finch warned all teams that parking would be limited due to ongoing construction. The promoter, Pace Motor Sports, rented 14 loading dock slots where the teams with 18-wheelers could park and work. Everyone else was advised to pack light because they would be pitted together inside an open area and had to carry in all their supplies. Team Honda still operated out of box vans in 1996. On race day, Norfolk and McGrath looked like a couple of weekend warriors; they had a bike, toolbox, lawn chair and gear bag sitting in the dank concrete underbelly of the stadium. McGrath was used to this type of setting from all the European races he’d attended, but in the States, with so much pressure building to earn a perfect season, Norfolk felt uneasy because he didn’t feel like he was in control of his surroundings.

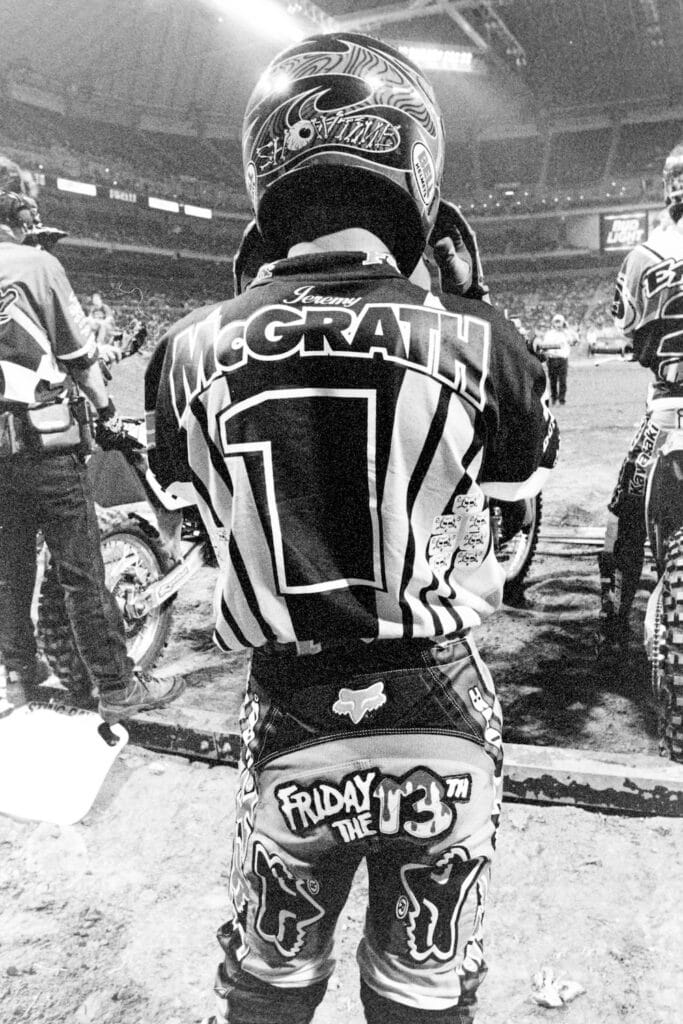

“We were standing there naked in a sense,” Norfolk says. In addition to maintaining McGrath’s bike every week, he typically ran interference and tried to make sure his rider had the space and time to mentally prepare each night. As the win streak lengthened the interview and appearance requests ballooned, as did the number of fans and friends stopping by for face time with Jeremy. Coming into 1996, McGrath was already, by far, the most popular rider in the sport. By the end of the season, his dominance had earned him – and the sport – coverage in USA Today, appearances on ESPN’s SportsCenter and RPM Tonight, outreach from local news stations and dailies along each stop, even Hard Copy did a hit. The promoters were also reaching out to the Tonight Show. Showtime was in high demand and Norfolk worked overtime to make sure his rider had space throughout race day.

“It wasn’t up to McGrath to say no,” Norfolk says. “He was Superman. Saying no was my job. I just tied Superman’s shoes. That’s all I did. Jeremy had an unbelievable ability to focus and turn things off and on. He could mentally talk himself out of arm pump. That’s how strong he was.”

Norfolk believes two types of spectators showed up that cool late April night: those who wanted to see Superman triumph once more and those who wanted proof that Superman really was Clark Kent. St. Louis was the closest thing Emig had to a hometown race in his professional career; raised 250 miles away in Kansas City, he bought a dozen tickets for family and friends and the 36,717 spectators in attendance were clearly split in allegiance between the champ and the challenger. The crowd was impressive considering that two other major sporting events were scheduled on the same day. Six tenths of a mile to the south an early afternoon baseball game at Busch Memorial Stadium was played between the Atlanta Braves and the St. Louis Cardinals. At the same time as the gate drop for supercross heat number one the National Hockey League’s St. Louis Blues and Toronto Maple Leafs squared off in conference quarterfinal game six, just one mile to the west. With 20,777 fans, the Kiel Center was at 108% capacity.

David Bailey and the Worst Elevator Ride, Ever

Back in the Trans World Dome, as the first heat race of the night lined up, 1983 AMA Supercross Champion David Bailey banged on the walls of the press box elevator while Art Eckman sat waiting for him in the television booth overlooking the stadium floor. Bailey, ESPN’s supercross analyst at the time, was stuck and alone and the emergency phone was either out of order or yet to be installed, Bailey can’t recall. What he does remember is that he was involuntarily quarantined for 71 minutes and may have missed the start of the race had it not been for Eckman who figured it out. Eckman and field reporter Marty Reid razzed Bailey on air all night. Even Emig got in on the joke in his heat race podium interview. After being lifted from the broken elevator by the fire department, Bailey came into the TV booth where Eckman sat with a friend, a gentleman in his mid-50s wearing a blue button down and gray slacks and who also happened to be wearing a TV studio headset.

“David, this is Bobby Cox,” Eckman said.

“Cool,” Bailey said as he tried to calm himself down, get into place, straighten his tie and don his headset. Then he thought to himself, “Who in the hell is Bobby Cox?”

After the ESPN Speedworld opening sequence, the supercross telecast opened with Eckman introducing Bailey and special guest Bobby Cox, a casual supercross fan and the general manager of the 1995 World Series-winning Atlanta Braves. On air, Cox talked about how the 1982 Braves also started their season with 13 consecutive victories, a record that was matched by the Milwaukee Brewers in 1987. As of spring 2022, those win streaks are still alive in Major League Baseball.

“This streak here,” Cox said of McGrath’s own run of a baker’s dozen, “it seems almost impossible to me.” Cox, now a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame had accurate analysis because three hours later his foreshadowing proved to be correct.

A Very Confident Jeff Emig

Gary Emig was excited. He thought his son’s bike looked faster coming out of the turns. Jeremy Albrecht didn’t understand how the elder Emig could eyeball something like that but he didn’t question it because the mood at the Kawasaki truck was spirited. Despite losing to McGrath for 13 consecutive weekends, Jeff Emig still believed he could win. Albrecht liked that about Jeff and being only 24 years old and in his first year as a factory mechanic, Albrecht did everything he could to please his rider and team.

This particular week, he installed a power jet on Emig’s KX250, an electronic piece that shot fuel into the carburetor exactly when the engine needed it, typically when its fuel mixture got too rich. Albrecht said electronics were still very new in motocross and they had only tested the part for two weeks. In practice, Emig had a minor get off but he was still upbeat; the track was rutted, the whoops – admittedly a huge weakness for him – were smaller and wouldn’t be much of a factor and the support of family gave him good vibes. Emig remembers lining up in St. Louis with a tremendous amount of confidence.

“I was always emotionally motivated,” he says. “Having [family there] inspired me to feel like I was on a date with destiny. I’m funny that way.”

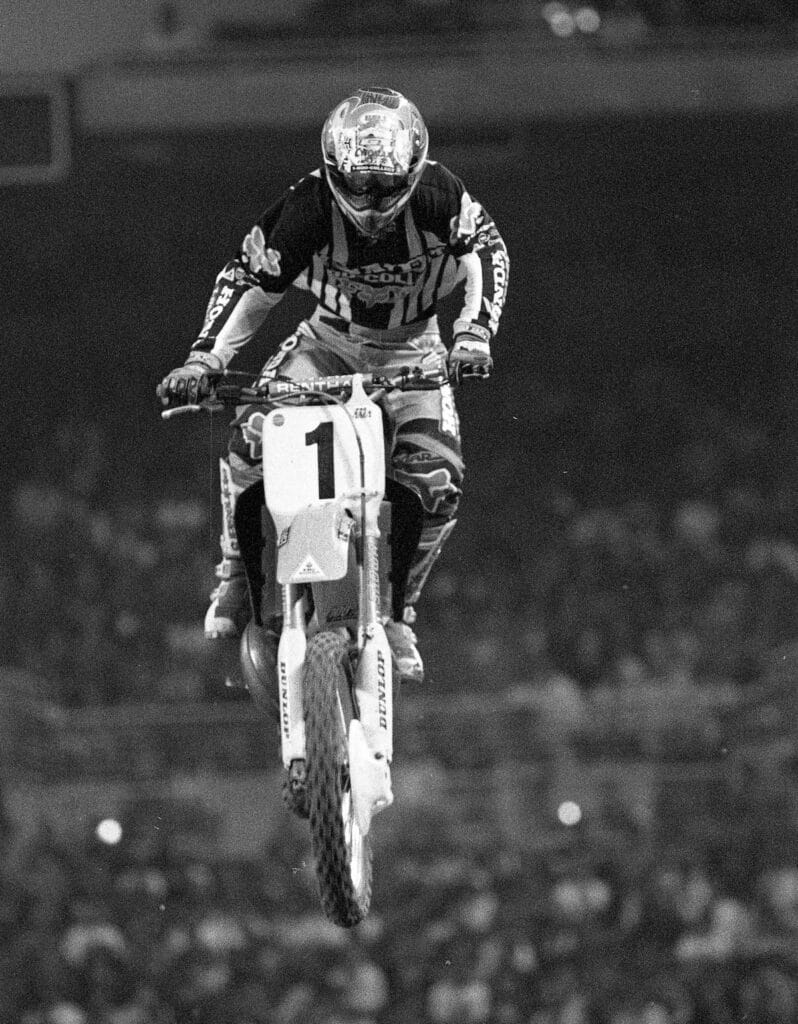

In heat one, Emig took a tight line around the left-hand first turn and led all eight laps but had constant pressure from Yamaha’s Doug Henry. It was Emig’s fifth heat race win of 1996. McGrath was the focus in heat two. ESPN hooked up a microphone to Norfolk’s team headset so the TV audience could listen in to anything he said to McGrath. When the camera hung out in front of McGrath’s gate for an almost uncomfortable length of time, Skip finally leaned in to tell McGrath that the first turn was soft and then he relayed a couple of scenarios. McGrath responded with ennui, even fought through a fit of yawning and simply told Skip what he wasn’t going to do.

McGrath won heat two but spent the entire race chasing privateer Phil Lawrence while both Mike Craig and Larry Ward took turns poking at the champ all the way to the last lap. Before the final turn, McGrath shot by Lawrence for the win. His total running time for the heat, however, was 7:39.830, 1.6 seconds shy of Emig’s victory time. McGrath had second gate pick in the main event. Emig set the fastest heat of the night only one other time that season.

Jeremy McGrath Goes for a Hike

McGrath’s Honda CR250 ran flawlessly in St. Louis but Norfolk’s biggest regret from that night was not being able to create an environment where Jeremy could mentally prepare. After the heat races, Emig sat in the private and warm lounge at the front of the Kawasaki trailer and studied film.

McGrath, on the other hand, was a sitting duck in the open-air paddock and he was asked by Pace officials to meet with executives from Anheuser-Busch, based in St. Louis. They were trying to close the beverage giant as a series sponsor and McGrath obliged. He left the paddock to walk – in full gear – to a room that he thought was nearby.

“That never happened,” McGrath says of the mid-program request. “It was a rare situation but I’m a pleaser. I want to help everyone and then some.” The meeting was in a suite on the other side of the stadium. “It felt like two miles,” McGrath recalls. Moving around the most popular person at a gathering of nearly 40,000 is a painfully slow process and by the time he came back to the bike he had just enough time to change his gear before walking to the staging area for the main event.

Norfolk didn’t get time to talk to McGrath about the bike or go over the heat race film and he was irked at himself for not trying harder to keep Jeremy nearby. The promoters ultimately didn’t close the sponsorship deal but six years later Bud Light – an Anheuser-Busch brand – became the title sponsor of McGrath’s race team.

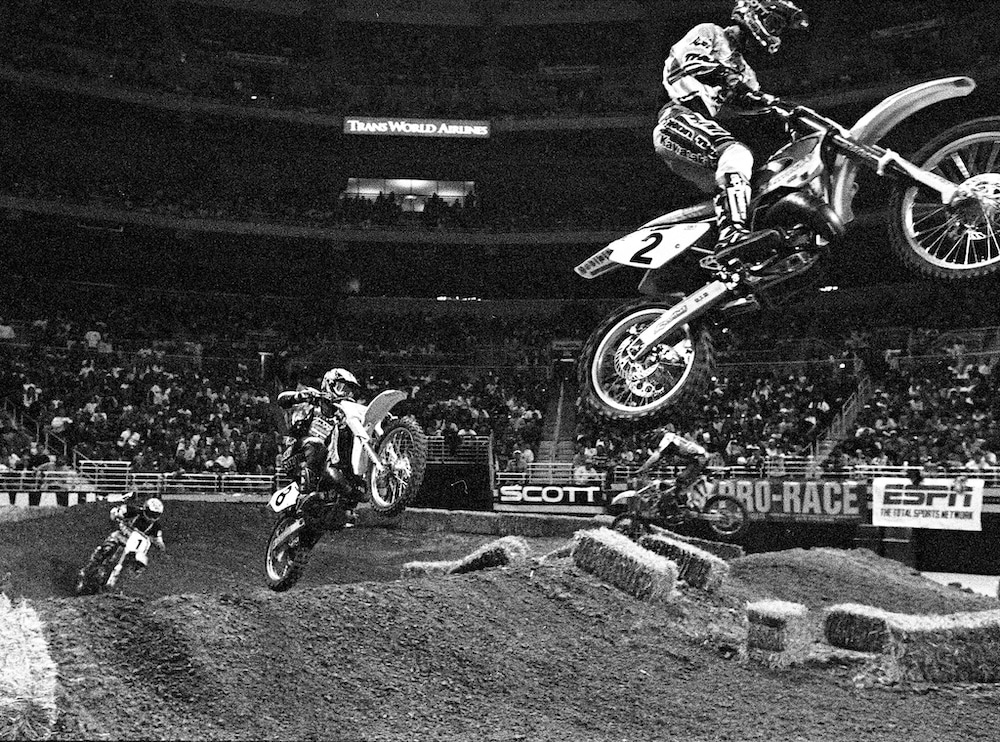

Jeremy McGrath: Almost Perfect, But Not Quite

In the main, Emig had first gate pick and McGrath, in a move that still baffles him, lined up to the inside of his rival. “I must have felt like I needed to be on the inside of Emig, he says. “That wasn’t normal for me.” Since McGrath typically had the faster heat race, he was accustomed to seeing Emig line up to his left; he couldn’t control that.

But when the roles were revered, McGrath said he usually avoided being anywhere near Emig, who started well and had a tendency to drift out of the gate. Albrecht says that was often part of Emig’s strategy and he was also puzzled when McGrath pulled into the inside.

“I remember races where Jeff would cut a guy off on the start on purpose because that was the only way he was going to beat him,” Albrecht says.

Because of moves like this, McGrath strongly disliked Emig. Although their relationship is cordial today McGrath doesn’t edit himself when discussing his feelings toward the mid-90s version of Fro. “His track etiquette was terrible. None of the riders liked racing against him. He chopped everyone off.”

Norfolk believed that McGrath usually had 17 of the other 19 riders beaten before the gate fell. Mike LaRocco and Emig were the exceptions and Emig remained hopeful even though he still hadn’t won a race over McGrath in his five years in the premier class. “I had it in my mind that he was beatable,” he says. “It was not easy to be rivals. I appreciate now the struggles and having an adversary and challenger that was such a great champion. As painful as it was sometimes, without that intense rivalry with McGrath, I might not have ever reached the success that I did have.”

Before the 30-second card went up Emig sat stone still on his bike while McGrath clapped his hands, rolled his head in circles and rubbed his forearms. After the bikes had fired up Norfolk reminded his rider that he only needed a holeshot and four hard laps and he could coast.

“You know who is on your right. You know where you need to be when the gate drops. Forget about your heat race.”

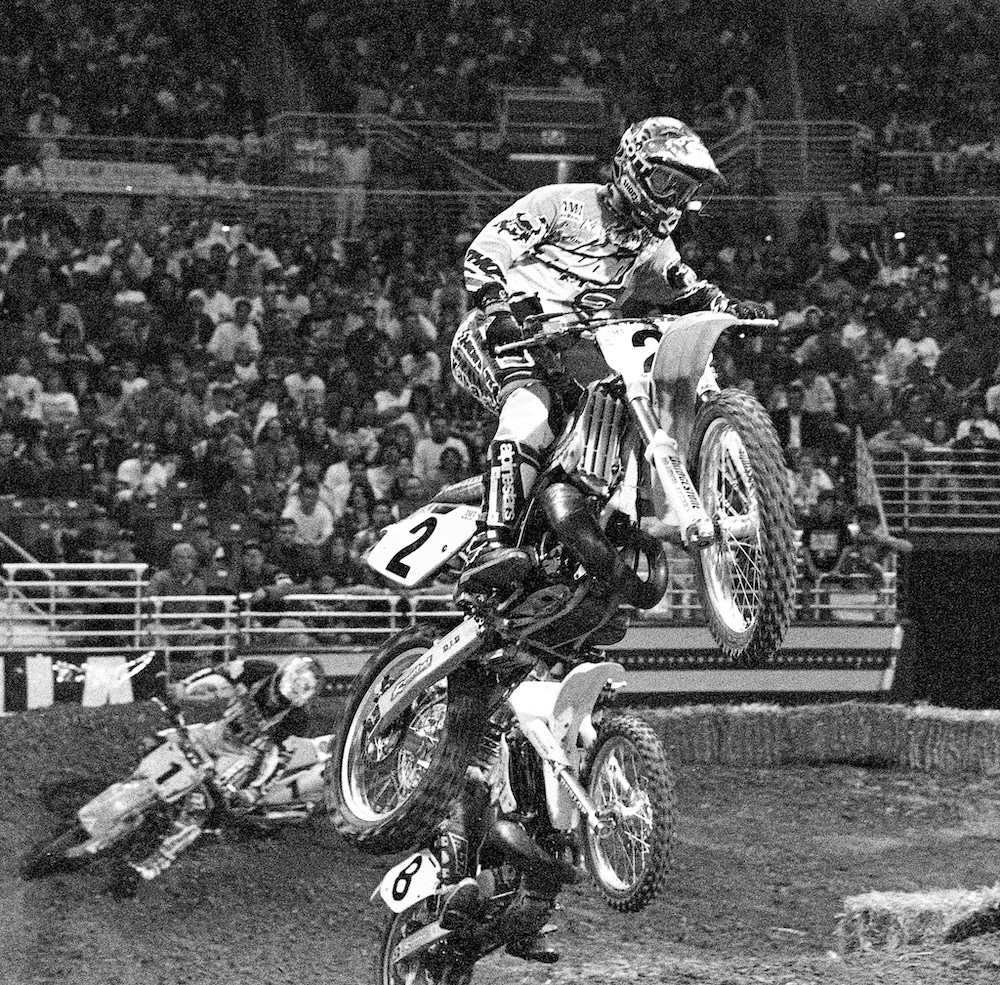

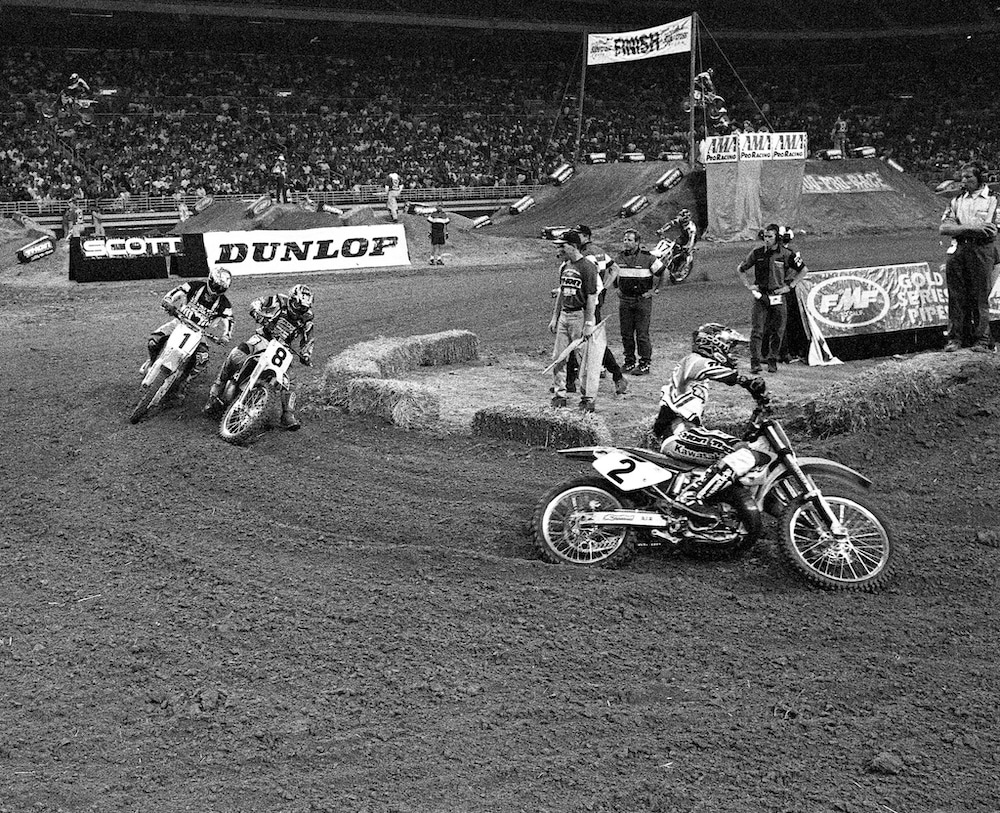

When the gate fell, Emig jumped out well and immediately shot to his left. Exactly as he did in the heat race, he hugged the inside of turn one and rounded the bend in the lead. McGrath was about 10th around the first corner but fifth coming into turn three. He spent nearly the entire first lap trying to pass Ezra Lusk for fourth and that was the last outright pass he stuck for the rest of the race. McGrath sat in fourth place until lap nine when Phil Lawrence, who nipped at Emig for the lead, cross-rutted on a roller and bounced awkwardly into a hay bale. On lap 10, McGrath was third and trailing behind two of the most difficult riders to pass: Emig and Suzuki’s LaRocco, a rider who rarely started near the front.

By the halfway point Norfolk was in the mechanic’s area with a knot in his stomach. The fact that his rider had sat in the same position for almost half the race – a position that wasn’t the lead – was foreign to him. He could see that Jeremy wasn’t on the balls of his feet, was making double foot dabs in the corners, casing small double jumps, losing traction coming out of the turns and not riding like a four-time champion. “That was not Jeremy out there. You could see it in how he rode. That’s what hurt the most,” Norfolk says.

On lap 12 the lead trio tightened up and McGrath blasted by LaRocco on the start straight when he picked up momentum in the corner after the finish line. LaRocco stayed close, pulled even over the triples and McGrath glanced over from the inside. In the next corner McGrath went for the middle of the 180-degree turn while LaRocco darted toward his front wheel. McGrath was slammed so hard by “The Rock” that both feet flailed off the pegs and he weaved to the other side of the track. LaRocco doesn’t remember the specific pass but in a text message inquiry says, “Sounds like something I would have done.”

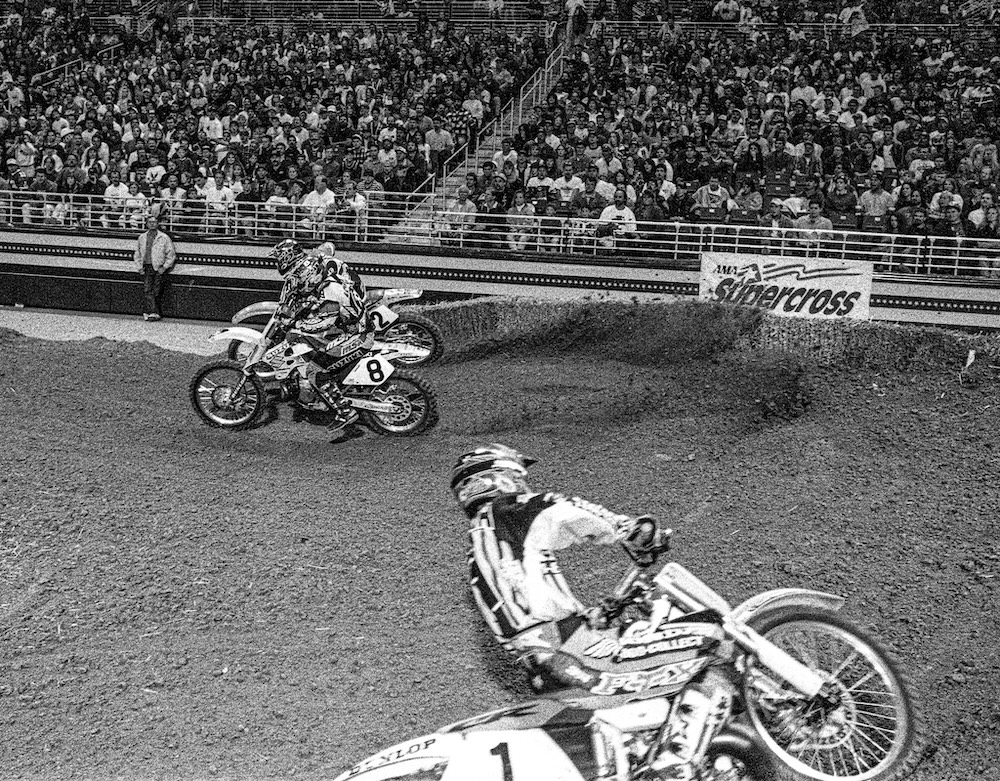

How McGrath’s night didn’t end right there is impressive. LaRocco then passed Emig in the same corner with a similar block but led for only 150 feet. Two laps later, LaRocco hit Emig from the inside again, this time in a 90-degree corner, but came in at such a severe angle that his left leg popped off the right side of the bike. He remounted without falling but McGrath swept by. McGrath had about six laps to pass Emig for the lead but every time he came close enough to make a move he’d case a jump or cross rut and lose momentum. The track deteriorated and became heavily rutted and choppy. McGrath’s analysis is that Emig won a fair fight but he feels that nobody rode very well that night. “It was a survival deal,” he says.

While being interviewed, Emig pulls up the race on YouTube and offers a different take. “I didn’t make any mistakes from what I can see,” he says. “I didn’t let the emotions of the race affect me in a negative way.” Today, Emig feels loss aversion – the economic theory that people prefer avoiding loss rather than acquiring gain – can sum up his entire supercross career. “I was riding good but conservative out front because I had something to lose… again. I had been in that spot so many times.”

For the final six laps while McGrath yo-yoed in second place, Emig appeared to not notice what was going on behind him. But he says he’d be lying if he didn’t admit to keeping an eye on McGrath. “Why would you not? The guy has just won every race. Of course you’re looking out for him.”

After losing his first AMA race since July 30, 1995, McGrath remembers feeling relief but he was pissed that it was Emig who beat him. He wanted it to be anyone but Emig. Even though he tried to downplay the pressure of the perfect season, in his 2004 book Wide Open McGrath admitted:

“It was starting to get to me.” One of McGrath’s greatest qualities as an athlete was that he was confident enough to expect to win every single race but when he didn’t he wasn’t upset. Expectations, he says, can sour a career and he made sure that winning didn’t become a burden.

“At a certain point you get so tired of the expectations that you wish they would go away,” he says of his observations of great champions in motorcycling and other sports. “You like winning but you get tired of the expectations and retire. That’s about the only way that you can push the reset button.”

The End of Perfection

The perfect season was over; Cycle News was finally off the hook from conjuring clever headlines and Fox Racing didn’t have the pressure to keep designing creative butt patches about the streak (“Str8”, “9 Lives”, “Hang 10”). But for Norfolk and Team Manager Dave Arnold – being employees of Honda – the pressure to win was always prevalent.

“If we didn’t win everything, every day, even if it was a good excuse, I remember hearing about it,” Arnold says. “I’m not exaggerating. [Honda was] tough. They wanted to bitch slap the other manufacturers back in time.”

McGrath doesn’t remember feeling that pressure to be perfect but the team personnel were careful to shield him. He also won more races than he didn’t. Norfolk however, was devastated after St. Louis and he remembers nothing in the seven days between the checkered flag and the morning of the Hangtown Motocross National outside of Sacramento, California eight days later.

The week was a complete fog and at Hangtown he was directed to park on a camber that required him to do some digging in order to level his truck. It was Sunday morning – race day – and he completely lost it. Standing in the sun with a shovel in his hand he fumed at the fact that he was being asked to park on a hill in the first place. Why wasn’t there more level ground?

“I felt like I needed to be perfect and if I have to be perfect, everyone needs to be perfect. I remember losing it on a guy that was just trying to help me level my box van.”

Emig didn’t win another AMA race until May 26, the High Point National. In 1996, the supercross and motocross seasons still overlapped and rounds two and three of the MX series fell between St. Louis and the final round of supercross in Denver. McGrath won all three of those races and Emig still remembers being on such a high in Denver that he didn’t care where he finished. “That one victory in St. Louis meant the world to me. It’s just one race out of hundreds but it’s a race that I am very proud of.”

By examination of the record books the residual effects of the win in St. Louis were huge for Emig. The day before the final supercross race in Denver, he did a video shoot with MTV Sports, an irreverent sports program that was interested in featuring the guy that finally beat McGrath. Emig went on to win 16 major AMA races through the end of 1997. He also won all three championships: the ’96 and ‘97 250cc (now 450) Pro Motocross titles and the 1997 Supercross Championship. The next highest win total was McGrath: 9 wins, zero titles.

Jeremy McGrath chuckles about how the race Jeff Emig is most famous for winning is the same race he’s most famous for losing. He doesn’t blame anyone but himself for what happened in St. Louis and he doesn’t believe there’s a hole in his resume.

The man already called Showtime later became the King of Supercross, probably the most honorary title anyone anywhere could have bestowed upon them. But Kings are still human and, for one night, even this symbolic monarch of sport couldn’t force perfection to his will.

And be sure to join our mailing list.