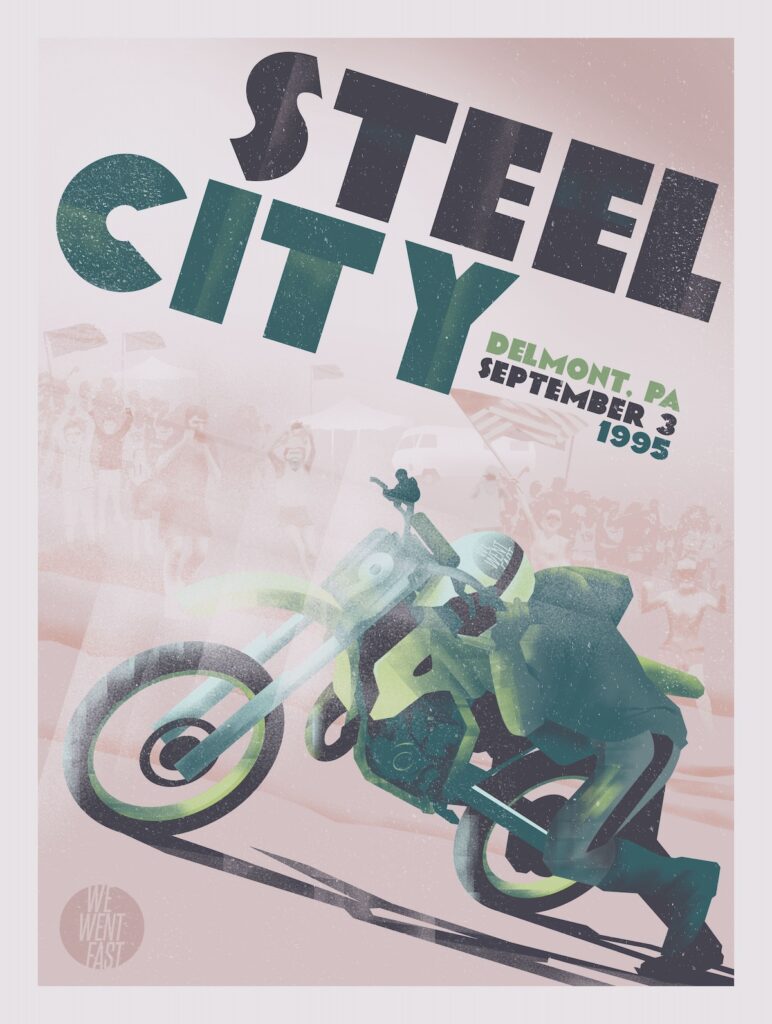

The Moment: Broken Hearts and Busted Chains

By

Wyatt Seals needed to borrow a chain. The story behind why he needed a chain is slightly different from the one his former employer, Mitch Payton, tells. Whether or not either version matters depends on how much you love details.

Let’s start with the indisputable facts: Seals turned wrenches for Ryan Hughes, who entered the final round of the 1995 125cc AMA Pro Motocross Championship three points behind Steve Lamson. Lamson was the sixth different rider that summer to either lead in the standings or tie for the lead, a minor miracle since the 24-year-old American Honda rider fell behind 61 points after the third round of the series. He started the 12-race season with 8-DNS-5 overall scores. Hughes experienced a few bad motos, sometimes rode on the edge but he finally found consistency. Entering the final round of the series, he had two wins and seven top three finishes overall.

For Team SplitFire/Pro Circuit Kawasaki, the morning of September 3, 1995 started with stress. Hughes came back to the truck after the first practice session and told Seals his bike vibrated too much. Maybe a main bearing, he recalls. The team swapped motors, a big enough task that Hughes missed the second practice session for his division. Race officials allowed him to take laps with the 250cc Class, which vexed Team Honda, but they made no formal protest.

Hughes remembers being completely unfazed by all this. Even the altercation he had with Brian Deegan earlier in the weekend (Pro Motocross had a two day format until 2009) didn’t rattle him. Deegan punched Hughes after the two went down together. Hughes desperately wanted to hit back but he thought about the stakes and consequences: a championship that could be lost because of a broken knuckle or a suspension from the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA). He rode away; he and Deegan still laugh about the incident today and Hughes is a riding coach to Deegan’s son Haiden.

“The more disruptive a situation is, the calmer I get,” Hughes said. “I’m very good at handling distress.” ESPN’s field correspondent, Art Eckman, reported on the engine swap and interviewed Hughes about strategy. Even though five different riders had won races in 1995, nobody doubted this race would be dominated by Lamson and Hughes. Damon Huffman, who didn’t win any overalls but spent the most time with the points lead (five races), sat third. He still had a very legitimate shot at the championship but his presence was barely acknowledged. With a three-point deficit, Hughes knew he had to win the first heat. Anything less would have left him praying for divine intervention.

“It’s do or die today,” he told Eckman before the race. “You guys keep the camera on me. I’m sure you’re going to see some pretty good stuff.”

The Chain

Spoiler: Ryan Hughes didn’t win the championship on that hot, sunny Sunday in western Pennsylvania. He did, however, live up to the promise he made on camera. Lamson took the number one plate but Hughes instantly became a legend. Only 12,000 spectators watched the event in person but decades later, even race enthusiasts born after 1995 know what Hughes did. They know, because Wyatt Seals borrowed a chain.

Everyone involved in this story agrees–and remembers–that they borrowed a chain from another team after the morning’s practice session. The sequencing and reasoning differ, however. Which version had a bigger effect on the day’s outcome? That’s hard to determine. Seals has deep convictions about his story.

In 1995, an RK 520 motorcycle chain–specifically, model GB 520MXZ–weighed 3.23 pounds and a D.I.D. ERT520 tipped scales at 3.17 pounds. In a 2018 phone call, company officials confirmed these weights by digging up brochures from the 1990s. The difference comes out to an almost insignificant 27 grams, approximately the same weight as a single AA battery. SplitFire/Pro Circuit used RK, still does, but Seals swore they used heavyweight grade RKs chains. They looked heavier, and when he compared the chains on the rear wheel of bikes from behind, he saw thicker sidewalls with RK. Payton is confident the team used a lightweight chain. All teams did at the time, he said, and he encyclopedically rattled off a half dozen instances where a chain broke in a major 125cc race, including riders from other teams.

“Everyone tried so hard to get this minuscule improvement of power and it was on the edge of the chain snapping,” Payton said of finding performance in the 125cc Class. “There’s a ton of tension on the chains. They recoil like crazy when riders land. You would be in the pits and wonder if everyone else was running a light or heavy chain. Pretty soon we were all running heavy chains and nobody talked about it.”

Seals admits he never did any actual weight comparisons, but he also had other reasons for preferring D.I.D. over RK. “The RKs stretched a lot when they were new,” he said. “They would get dangerously loose. I was leery about starting a race with it.” After practice, Seals felt Hughes’ number nine KX125 needed a new chain and using an RK was out of the question. He consulted Payton and Mike Hooker, the team coordinator, and cleared it with them. The he walked over to Honda of Troy’s truck and hit up another mechanic for a favor.

“That one came out of my van,” said Shawn Persinger of the chain Seals borrowed. He still remembers the chain’s model number, a D.I.D. ERT520. “It wasn’t an OEM chain but it had all the same materials as an OEM chain. It had a smaller side plate so it didn’t rob as much horsepower from the 125.”

Payton’s memory is different. After practice he recalls Seals asking him to look at a kink in their RK chain. Two kinks, according to Payton. The team had exhausted their supply of new chains. On the road since May, it was normal then for a truck to go low on parts, but completely running out of chains was an oversight. Payton said he agreed that they needed to replace it and that’s why Seals borrowed the chain.

Seals said he did see a kink in the chain that day, but in the afternoon, between 2:00 – 3:00 p.m., following the first moto.

This Was For Dad

Ryan Hughes’ father documented all of his amateur races with a video camera. With a VHS Camcorder, he recorded every moto, start to finish, which Ryan watched on loop throughout the 1980s. “That’s what I think made me improve so quickly,” he said. “I didn’t know what I was watching but I watched them.”

Hughes didn’t enjoy motocross at first. In fact, he didn’t want to ride at all. He played soccer, baseball and loved football so much that he had dreams of playing professionally. An angry but shy child, Hughes fought a lot but he didn’t seek attention. He didn’t want people looking at him, didn’t want to be noticed or in front; he often stared at the ground. “My mom said I came out angry.”

Dad worked at the San Onofre Nuclear Power Plant between the Southern California beach cities of San Clemente and Oceanside. Mom was the vice president of a bank. Riding didn’t become a serious activity for Ryan and his brother until 1984 when they were 11 and 13, respectively.

That year, at Barona Oaks Raceway, Ryan sat in his dad’s truck, crying, saying “No, no, no, I don’t want to go!” An irrational fear of being on the track with other riders paralyzed him. Mr. Hughes eventually convinced Ryan to do some laps on his Suzuki RM80. He crashed. To this day, Ryan remembers exactly where on the course it happened. Then, a man on a Suzuki 125 stopped to assist him and lift the mini cycle off his leg. These people are nice, he said to himself. “For some reason that changed everything for me.”

Armed with endless acreage of riding areas around his Escondido, California home and a father with a camera, Hughes went from the beginner class in 1984 to top five finishes as a professional in 1990. Injuries, however, derailed the young and promising Team Green Kawasaki rider. In 1991 he spent several months riding with a wrist he didn’t know was broken. After surgery in May, he didn’t line up for another AMA race until the following March. The injuries piled up, oddly on his right side and he spent his entire career riding out of balance with his body; he still doesn’t have an ACL in his right knee. He spent too much time on the ground and too little time on the podium. The first year he raced an entire season was 1994, an achievement marred by a bigger tragedy than a broken bone.

In the fall of 1993, George “Bill” Hughes Jr. came out of the bathroom and said to his wife “I’m dying.” At only 53, a doctor diagnosed him with terminal colon cancer. The word ‘terminal’ didn’t register with Ryan and he “put blinders on”. He remembers the verbiage in the hospital wasn’t “Your dad has cancer”, rather, “Your dad is dying.”

On Sunday, January 23, 1994, Bill Hughes died. Ryan raced the Houston Supercross the previous evening and didn’t make it back to Escondido in time to say goodbye. Fatherless at 20 years old, Hughes competed in Anaheim, 80 miles up Interstate 5, two days after Bill’s memorial service. With his emotions in a shambles, he didn’t qualify for the main event.

“I didn’t think it would affect me like that but I had a hard time concentrating all night,” he told Cycle News. A week later, at his hometown race in San Diego, he won the first major professional race of his career. On the podium he held the trophy above his head and yelled, “This is for you, dad!”

Despite the goose egg in Anaheim, Hughes rode with consistency and vigor. He finished fourth in the 125cc West Supercross points. In motocross, he finished third, 28 points behind the champion, Doug Henry and seven points behind Steve Lamson. Hughes already worked hard but after losing his father, he poured everything he had into training and racing. He’d do anything anyone asked of him. At the end of 1995, he wasn’t racing to win the motocross title for himself, or even Mitch Payton. He raced for Bill.

Afternoon: September 3, 1995

Hughes won the first moto. On a dry, dusty track that resembled his childhood riding areas, he started fourth and ran Lamson down within a few laps. In a sign of a bygone era, the leaders clocked regular lap times of 3:30, comically long by today’s standard of 2:00-2:15. In 1995 no regulation existed for limiting the length. Lamson had to get aggressive to pass early race leader Kevin Windham and on the final lap of the moto, he tried hard to make a move.

By winning, Hughes tied up the points and created a one moto run-off. Lamson told Cycle News’ Davey Coombs that he had no strategy other than “tear it up.” Hughes, effectively, said the same thing. “I guess I’m not dead yet, but I know that it’s really do or die this last moto.” To ESPN, he said, “If I ain’t going to win, I’m going to crash.”

Wyatt Seals ran through his normal routine of washing the bike, which included getting the chain as clean as possible. When finished with the pressure washer, he sprayed WD-40 on the chain to displace the water. While the WD-40 did its job he checked bolts, cables, controls, tires, carburetors, etc. He always applied chain lube and gassed up the tank last. Slowly spinning the wheel while applying the lube, he found a kink. He tried to free it up, thinking maybe a sliver of rock had lodged into a link but he couldn’t break it loose. He estimated the kink to be 15-20 degrees upward, very slight. He called Payton and Mike Hooker over to see it and they all agreed to leave it alone. He knew he had taken the last chain from Honda of Troy. Although RK made a great chain, he didn’t want to use a new one because of the way it stretched (but remember, Payton insists no chains were left on his own truck).

“You see stuff like this on a practice bike and you run it and it never gives you a problem,” Seals said of the small kink. “I had no stress about it at all. There was other stuff to worry about.” Mike Hooker remembers a “quiet confidence” in their paddock area. “It was very quiet and surreal.”

Hughes lined up behind the most inside starting gate for the second moto. Lamson placed himself one position to the right. Lamson took the holeshot and Hughes got pushed to a wide line in turn two. Denny Stephenson got bucked and sent Kevin Windham careening into Hughes’ back wheel. Windham crashed but Hughes came into turn three in fifth. Other than the sketchy skirmish at the start, nothing exceptional happened over the next 35-ish minutes. Payton, Hooker and Seals said very little over their radios. Little happened to give them a reason to chatter.

The track crew watered the course between races and Hughes collected every bit of moisture and mud. After one lap he looked like he had ridden through a bog. At the beginning of the second lap, Hughes moved past Mike Brown for second. With a clear path to Lamson, he went to work but no matter how hard he twisted the throttle, it made no difference. “Lamson rode as perfect a race as anyone could have ridden,” Seals said. “I feel that Ryan did the same thing.”

Hughes couldn’t catch Lamson this time. Like a recurring bad dream, the kind where the hero freezes in place and can only watch life happen around him, Hughes was stuck. He rode as fast as he could but went nowhere at the same time. He’d gain a second and lose a second and for the entire race, the gap frustratingly remained at four or five seconds. “That second moto, I’m sure I gave him the pit board but I bet there were three to four laps that I didn’t put anything on it,” Seals said when asked what he tried to communicate to his rider. “There was nothing to say. He was giving it all he had.”

The two title contenders demoralized the other 38 riders. Mike Brown, the series points leader after round seven, circulated in third, and drifted to one minute behind. On the final lap, Hughes went into ‘full send’ mode. Witnesses still talk about how fast Hughes hit the corner behind the starting gate, like the throttle was stuck open. Alas, he didn’t dent Lamson’s lead or even rattle him.

“I couldn’t do anything,” Hughes said. “But I have no regrets. That day, I lived up to what I was supposed to do. I chased that f—ing leader as hard as I could but he was awesome that day, too.”

Derailed

Chris Hultner had a fresh roll of slide film in his Nikon and he waited at the finish line to capture the championship celebration. Around the same time Lamson crossed the line and won title, however, Hultner heard the announcer change direction and exclaim, “He’s pushing his bike!” Hultner realized Hughes had not come around the bend at the bottom of the hill. He broke away from Lamson’s fist pumping to search for Hughes.

The Steel City course may have been long but it was unique in that it sat in a valley and offered maximum viewership to the spectators. The finish line sat in the middle of a hillside. Riders came in from the other side of the hill via an off camber, blocking the view of the approach. In the 40 seconds before the finish line, riders rode straight westward down a series of supercross-style tabletops, turned 180 degrees left and came back through more manmade jumps.

A 90-degree right hand turn sent riders up a short hill with a double jump placed strategically in the path. Rolling both jumps sucked away precious seconds from lap times but completely clearing the jumps caused riders to come into the left-hand corner that followed too hot. Riders who opted to jump the double often came up short on purpose to slow their speed and allow them to protect the inside line in the corner. The track then followed the contour of the finish line hillside. A long right-hand off camber took riders down and around to the bottom of the hill. The course then turned right and went straight up to the finish. At speed, the final approach to the finish line—following the off-camber—took approximately four seconds.

Focused on Lamson, the ESPN television coverage missed the exact moment Hughes’ chain broke. He was at least 150 yards from the finish line. It most likely snapped on the harsh landing from the short uphill double because Hughes coasted along the off-camber descent. Knowing that an uphill lay ahead of him, Hughes stepped off the left side of the motorcycle and ran with it when his momentum waned.

Jeff Stanton, a recently retired three-time AMA Pro Motocross champion now working for Team Honda, walked by on the outside of the course and cheered Hughes on. All the riders and mechanics on the starting gate for the final moto of the 250cc Class turned to see the action unfolding directly behind them. They raised their hands to shield the sun that was low in the sky. When Hughes hit the hill’s transition, he came to a complete stop. He turned his bars to the left, re-gripped and started marching.

Nothing was on his mind, not his late father, the failed championship or his level of exhaustion. Spectators, track crew, photographers and team personnel ran to the finish line to see him, like he had some type of magnetic pull. The crowd at the fences swelled. Lamson had just completed what is still one of the greatest comebacks in AMA Pro Motocross history and nobody outside of Team Honda cared. All 12,000 spectators and everyone else present focused on Hughes. Lamson did something heroic, earning a label that will forever remain attached to his name: champion. But Hughes cemented a legacy and became a legend in 60 seconds.

The price he paid came at the expense of unimaginable punishment. The act of pushing a 200-lb. motorcycle up a steep incline is not the sum total of the feat. The guy had already lost. The race, the championship he wanted more for his father than himself, was over. He had fought as hard as he could for nearly 40 minutes. It was almost perfect, but not quite. To dig up the will to keep going was the first anomaly. He didn’t throw the bike down or kick it and walk away. He didn’t even look down at the bike and make the frantic hand gestures athletes do when they’re trying to communicate frustration. He just… kept going.

“I wasn’t trying to prove anything,” he said. “It was instinct. It was ‘f—ing finish’. That’s been my life. Just finish. I hadn’t seen the checkered flag yet.” Hughes said his mind was blank, like in a meditative state. Lappers rode around him to the left and right. He shifted his hand position and placed his right hand on the rear fender, which opened his chest and allowed him to bury his helmet into the handlebars. Pushing with his head gave relief to his arms. The march turned into baby steps and he focused on finding traction with his toes. The dry, slick ground caused him to slip. He stalled. He pushed in spurts. When he found a bit of momentum he capitalized on it. Had he slipped too much and lost control of the bike, he may not have been able to pick it back up and continue. A man in a white t-shirt ran down the hill toward him. He came within two or three feet of Hughes but then abruptly turned around and walked back uphill toward the finish.

“There was a fan,” Mike Hooker said. “I don’t know if he came from the fence or was already in the infield but he was about to try to help Ryan push up the hill (a rule violation). I remember telling him to stop. We went from not winning the title to this guy is going to be a hero just for finishing this moto.”

Win or lose, Wyatt Seals wanted to be at the finish line and he ran there shortly after the leaders went by the mechanics’ area on the final lap. He doesn’t recall hearing the announcer yelling but he does remember Lamson coming up the hill first and then… nothing. He didn’t panic. He figured Hughes fell in a valiant last-ditch push to pass. Then he heard someone holler ‘chain!’ and his gut dropped. Hughes came into view at the bottom of the hill. Stanton, making his way to the finish, gave Seals a bit of solace, telling him Hughes was not in front of Lamson when it happened, that the broken chain didn’t cost the team a championship.

“That, selfishly, was a load off,” Seals said. For Seals, the episode seemed to last as long as the entire moto. He noted how many people urged Hughes on, even mechanics from other teams.

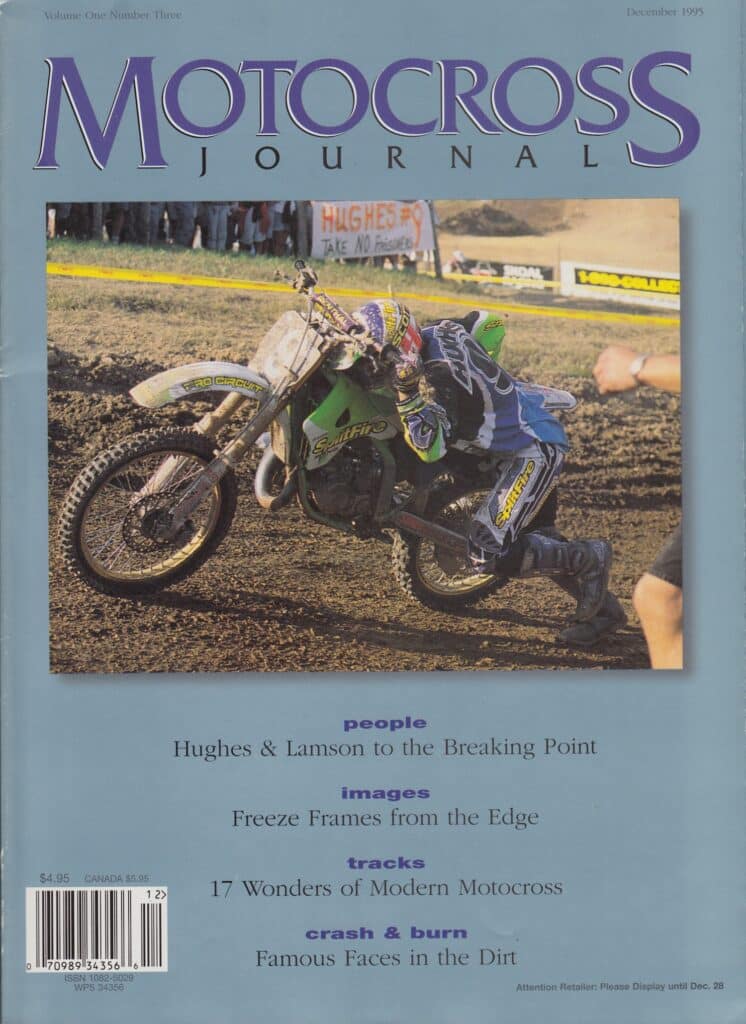

Hughes remembers the steepness of the hill. “You don’t notice it when you’re riding.” He used the bicyclist’s mantra, ‘the top is right here, it’s right here, it’s right here,’ and controlled his breathing like he would in any workout. Weeks later, when he saw the race coverage (it was tape delayed on ESPN) he couldn’t believe how many people had gathered at the fence and in the infield. When he saw Chris Hultner’s photograph on the cover of Motocross Journal, he cried.

Hultner wasn’t the only photographer around but he moved with the most urgency. “I kind of panicked because I knew I had to get a photo of it,” Hultner said. “I started running and turning the dials on my camera because I knew he was going to be backlit.” A Hi-Torque Publications staff photographer, Hultner’s images appeared mostly in Motocross Action but in the summer of 1995, the upstart sister title, the lifestyle-focused Motocross Journal, gave him another outlet for his craft. Shooting slide film with a Tamron 2.8 80-200mm lens, Hultner hustled himself parallel with Hughes but couldn’t get too close because he didn’t have a wide field of view.

A pro in the profession, today Hultner says he “winged it” but he still had the foresight and ability to analyze the situation. He slowed down the shutter speed and opened up the f stop; he focused manually. “I didn’t have time to set up my exposure correctly. I ran alongside of him without running into people. It was mayhem.”

Roland Hinz, Hi-Torque’s president, still picks the cover shots of all his titles and he likes to have several choices. When Hultner and the editors gathered for the December 1995 issue of Motocross Journal they included only one exposure in the cover stack, a shot of Ryan Hughes walking his bike, a very unorthodox scene. His visor was wedged near the steering stem, his left hand clawed at the end of the grip. His face rested against the space where the seat and the gas tank meet and his torso bent parallel to the ground.

While his right foot pushed off, his left foot was suspended in mid step. His jersey was untucked, his right elbow pointed behind him because his right hand pulled and pushed, grabbing the space where the rear fender and number plate connect. Above him in the frame, but maybe 35 feet away, a hand painted banner hung on a fence: “Hughes #9” it read in orange, “Take NO Prisoners” in black. Mike Hooker’s hand and knee crept into the right side of the image.

“It went along with everything we were trying to do with the magazine,” Hultner said. Roland immediately agreed to put the photo on the cover.

“What heart and determination,” Stanton said he still thinks every time he sees the photo. Known for his own legendary work ethic, Stanton watched the entire push and spoke with Hughes afterward. “He finished what he started. It’s unteachable. Ryan had that gut, that ability to work hard. And he often worked too hard, which I also did late in my career. But how do you knock that?”

The closer Hughes got to the finish line, which was a left-hand corner at the top of the hill, the louder the crowd yelled, as if their energy transferred into his body. About 64 seconds after Lamson crossed the finish line, third place Mike Brown came around Hughes to steal away second place. It didn’t change the day’s overall score (Hughes finished second) but it did mean that Hughes lost the title by five points instead of three. It’s a minor detail, one of those pieces of record book trivia that can’t be explained in names and numbers in print. The record book will never reveal just how close Hughes came to winning this championship.

Seven seconds after Mike Brown wheelied by on the right side and across the finish line, Hughes reached the corner. The course flattened out and his pace quickened. He collapsed into a bank of dirt, the bike fell on top of his lifeless legs. Hooker reached him first. He said something to Hughes but he can’t remember what. Then he picked up the bike. Hooker dealt with his own inner struggle that day. A Pro Circuit employee since the early 1980s, he used to ride his bike to Payton’s shop after middle school to clean rust off two strokes pipes with muriatic acid. His issue in 1995 stemmed from his personal friendship with Lamson, who lived with the Hooker family for nearly three years (1990-1992). Lamson also rode for Team Peak/Pro Circuit Honda in 1991. He took the fourth and final spot on the team on Hooker’s recommendation.

“I had to separate those emotions,” Hooker said. “I didn’t want that personal relationship to get in the way or influence Ryan’s results that day and even the year.” Hooker couldn’t outwardly express the joy he felt for his friend but he remembers how crushed he felt for Hughes. “I wish, for all the effort that Ryan put into his career and craft, the heartbreaks he experienced, I wish he’d won a title. He didn’t not win for lack of trying, that’s for sure.”

“That was one of Ryno’s defining moments in his whole career,” Seals said. “If it had cost him the championship, the story would be different. But it didn’t. It’s funny how people think it cost him the title and have written that.”

Today, Hughes is thankful the chain snapped. “I wouldn’t have got shit out of it if I had just rolled across the line in second,” he said, laughing. Hultner’s image became a metaphor for his life and the brands he created, Ryno Power and The Ryno Institute. It’s even the profile pic for his personal social media accounts. He gets asked about that day often. While he has no regrets, he would rather have the number one plate. He didn’t need to go through that to prove he wasn’t a quitter. Fans would learn that later, in other feats of grit.

“Would I take the championship now? Yeah. It would have been a nice bonus,” he said. “But that memory and picture will go down in history. There’s now this iconic memory of something that came as instinct.”

Prologue

They found the chain. Someone dug it out of the dust and walked it back to the Pro Circuit truck. Seals examined it and couldn’t locate the spot with the kink so he assumed it lay in the dust. He went back to the track to look for the broken link but didn’t find it. After Hughes cooled down, his positive attitude returned; he got focused again. He had to.

The next morning, with Lamson and Jeff Emig, he flew to Europe for the Motocross des Nations in Slovakia. In 1994, Team USA lost the race after a 13-year winning streak. When riders such as Mike Kiedrowski and newly crowned 250cc champion Jeremy McGrath declined a spot on Team USA, Hughes stepped up and rode the beastly KX500 in the Open division. Lamson and Jeff Emig competed in the 125 and 250 classes, respectively.

Despite six moto scores of third or better, Team USA lost to the Belgians by a single point. Just like at Steel City one week earlier, one pass would have won the title. This time, however, it was a team effort and each one of them shouldered the responsibility. Hughes finished 2-2 on an unfamiliar bike, in a foreign country. Lamson finished 3-3 and Emig 2-1. In any other year, those scores win the event, but Belgium rode just that much better, just as Lamson did against Hughes seven days earlier. Another heartbreak.

In 2000 Hughes got to be part of a winning Motocross of Nations team. But he never won a championship. He did continue to win respect. In 2003 he came out of retirement at 30 years old for another crack at the 125cc title. A test rider and consultant for Red Bull KTM, he felt just as fast as the kids on the team. So, he lined up and raced.

He finished on the podium in the first three rounds and won in Sacramento. In Southwick, Massachusetts, however, he fractured his left fibula in the first moto; he still finished 10th. He got X-rays between motos, iced and taped the leg and finished 16th, despite the feeling of loose bones moving around. He missed round five and only lost the title by seven points in yet another bittersweet ending out of his control; flooding forced the cancellation of the finale. Robbed again.

Today, through The Ryno Institute, Hughes travels the country and the world, teaching and coaching motocross. He focuses on technique and fundamentals first rather than speed, heart rate and lap times. Body positioning—feet, knees, hips, core, arms—is so crucial to perfect before worrying about going fast, he said. He figured all this out around 2007, the same time the paychecks stopped showing up in the mailbox.

“It’s my service to this sport,” he said. “I’m absolutely obsessed with motocross.”

As Jeff Stanton said, what Hughes did on the hot afternoon of September 3, 1995 is unteachable. Instinct comes from within. Hughes doesn’t teach riders how to push motorcycles up hills but when conversations get philosophical, he has a credo he loves to share: “A guess will last for a second, but a dwell will last for days.”