Doug Henry’s 2.8 Seconds to Legend

By

The story behind how small errors, fatigue, pride, determination and a wardrobe issue caused Doug Henry to take the most notorious flight in motocross history.

Everybody responded differently to what happened. Some of the sunbaked spectators processed it slowly. Others reacted immediately, but were clearly unsure what exactly they should do; one shirtless man, holding a koozie-wrapped can in his left hand, ran from outside of the camera’s view, hurdled the fence steeplechase-style, and just stood near the rider’s feet.

Some spectators stood there, slumped over the barrier, motionless; others slowly raised their disposable cameras to their eyes and snapped photos. Many pointed back up the hill as if they were still trying to convince themselves of what they just saw and from where it came.

The Witnesses

Stacey Henry saw it happen from the back of a Honda box van. She watched the race but wanted relief from the oppressive Father’s Day sun and humidity that blanketed southern Maryland. She had a head-on angle but far enough away that she said to herself, “What kind of line was that?”

A couple of seconds passed and she wondered why her husband hadn’t gotten up yet. Doug always bounced right back up. Then John Dowd’s wife, Trish, came over and told her to get down to the track.

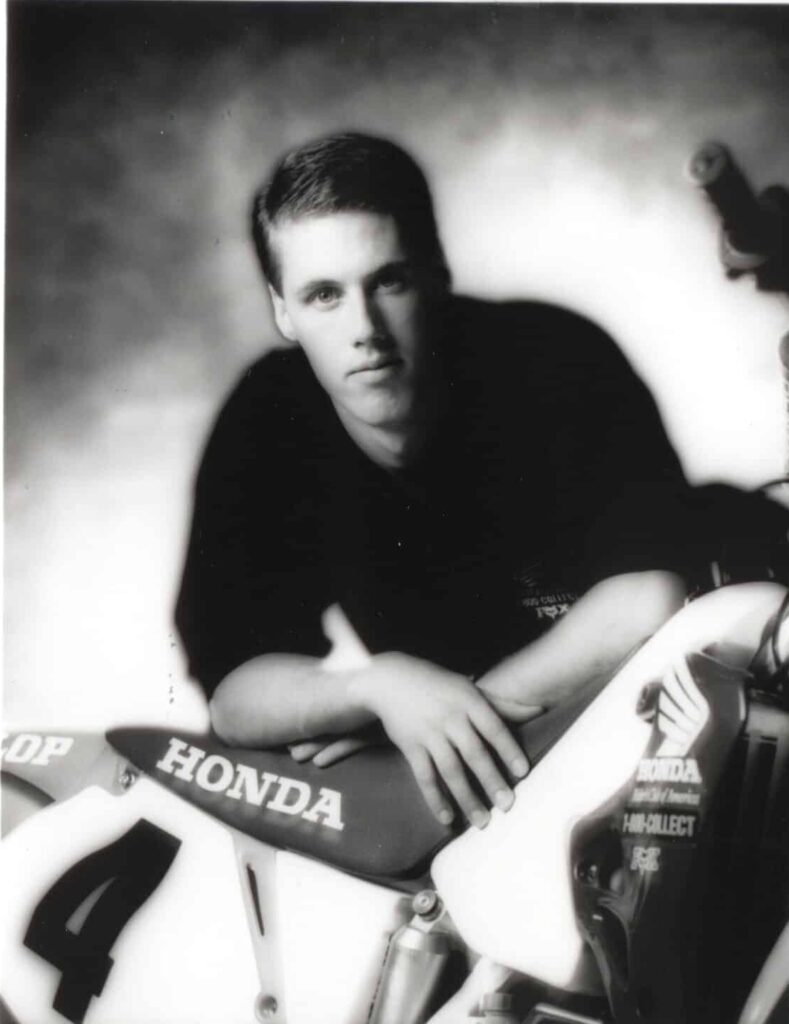

Autographed: John Dowd & Doug Henry

Jeremy McGrath didn’t understand why he heard Doug Henry’s engine accelerating through the braking bumps. McGrath had moved slightly to his right to avoid the uphill chatters and thought, if he ran it in deep on his teammate, he could gain a few tenths of a second.

He looked to his left and saw Henry hanging off the back of his bike and then float away like a Nordic ski jumper. McGrath let up. Henry gained velocity and height by the time McGrath started descending from his own jump. “I thought he was dead,” McGrath says.

I thought he was dead.

–Jeremy McGrath

Davey Coombs turned around just in time to see something fall out of the sky and hear what he called a “sickening thud, the sound of metal breaking and a bomb hitting but not going off.” He was shooting photos and writing for Cycle News. He and Motocross Action’s Chris Hultner were loading film into their cameras.

They looked at each other and raced toward the fence.

Jonathan Beasley had been awake for two days preparing his racetrack for this day, the fourth round of the Pro Motocross Championship. He faced the course and specifically remembers talking with someone who stood at his own towering height: 6’4”.

Support Story Telling!

Chatter from his two-way radio filled the other ear. He saw the whole thing and still calls it one of the scariest moments of his life. The radio noise died; Beasley hopped on his ATV and took off.

“Doug was probably 70 feet in the air at the height of that jump,” he says. “It was just sad seeing how he fell like a rock.”

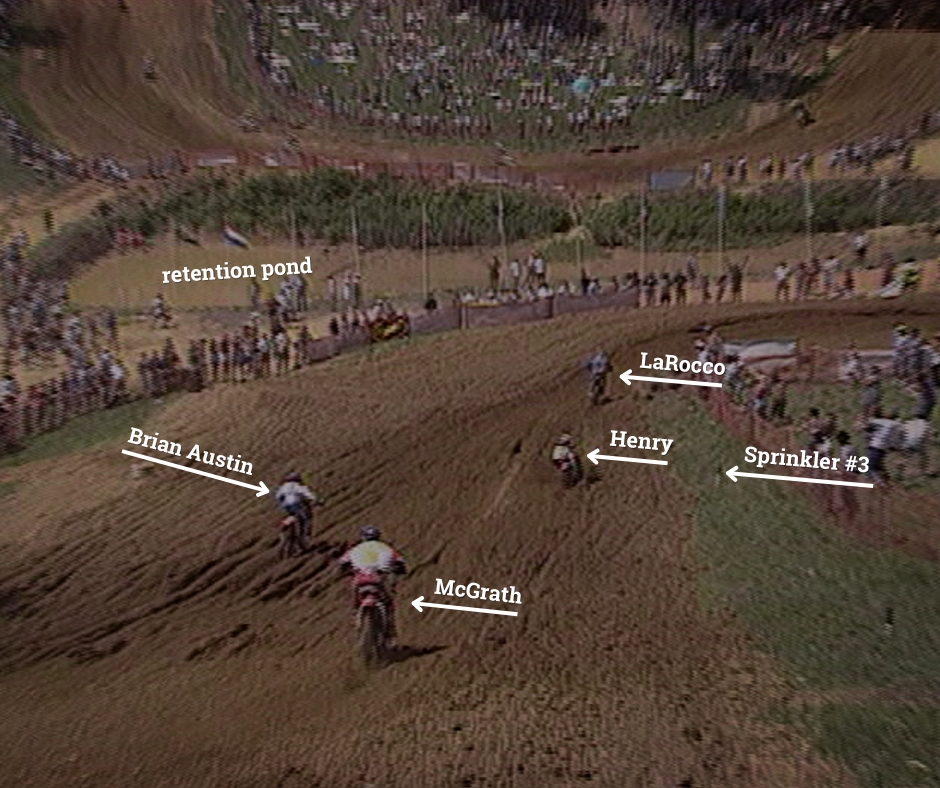

Brian Austin was racing in the moto, but a lap down. The leader, Mike LaRocco, had just passed and Austin knew that second and third would soon follow. Then he heard something that wasn’t quite normal and he looked over his right shoulder. Nothing. Then he looked up—way up—and saw another rider in the air at an obscenely abnormal height.

Austin was 10 to 15 feet away from where Doug Henry landed and the most vivid and disturbing memory was that he actually felt the ground shake. “I could feel it, hear it, and taste how much compressive force happened,” he says.

Shelton Hines, a lanky construction worker from Columbia, Maryland reached Henry’s side first, within 10 seconds of him landing. Hines jumped the fence and in long strides walked to Henry and picked up the discarded purple Scott goggles.

“It looked like his eyes were rolling into the back of his head,” Hines says. “It was pretty bad.” He remembers being asked for water and then dropping the goggles and attempting to remove Henry’s helmet. Within seconds, an EMT shooed Hines away. He and three other random spectators, who all ran in from different directions, scattered.

Understanding What Happened

An obvious statement: Doug Henry’s June 18, 1995 crash at Budds Creek Motocross Park in Mechanicsville, Maryland, is one of the most infamous and bizarre motorcycle wrecks of all time. But to merely describe it as a crash is a gross misrepresentation of what actually happened. It was more like a flight, then a plummet.

In trying to learn why this incident will be forever be memorable, first understand that Henry did something that had no possibility of yielding a benefit. “If he had landed it…” was not an option. He didn’t crash attempting a unique jump combination or endo or high side or swap out of control; he sent himself into the atmosphere seemingly on purpose.

For everyone who witnessed the crash, it was completely nonsensical. For most of the spectators, Henry had come from completely out of view to suddenly five to seven stories in the air. People were forced to make their own conclusions.

In 1995 there was no live TV at motocross races, or even a TV truck from where team and race officials could get answers. Cameras captured footage on physical tape that had to be edited together. ESPN aired the footage a week (sometimes two) later.

In Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers, a book that examines the factors that lead to high levels of success, one chapter makes an argument that plane crashes do not happen as the result of a single catastrophic cause. Instead, Gladwell says, plane crashes are a subtle process that begin slowly and gradually overtake the pilots until the plane ends up in an unredeemable crisis.

Doug Henry, the only person who truly knows what led to his own crash from flight in 1995, would agree. From small mistakes to fatigue, pride, determination, a wardrobe issue, and even bike setup, a series of factors led him to be dropped from the sky that day.

Doug Henry vs. Jeremy McGrath

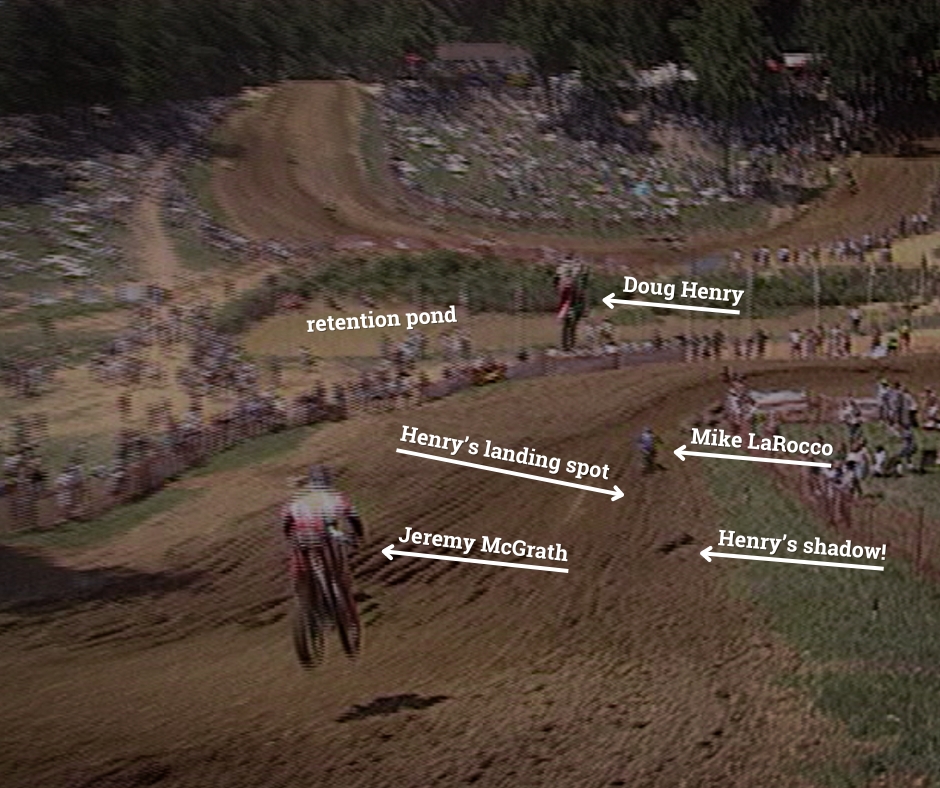

Henry battled McGrath for second place. They were halfway through the second-to-last lap of moto one and the defending series champion, LaRocco, was less than two seconds ahead of them. In a rutted left-hand corner, in a secluded area of the course, Henry took the inside, McGrath the outside. McGrath saw Henry make a mistake in the corner and gained a little time.

Then Henry, on his number four Honda CR250R, cased the downhill double out of the corner and nearly landed on an automobile tire that served as a crude track barrier.

McGrath downsided it cleanly and closed more distance on his Honda teammate. The riders then raced into the bottom of a valley before climbing another steep hill. Henry hit a bump with a square edge; the suspension compressed and his body position shifted so far back his butt patch rubbed the stickers off his rear fender. His feet also hung off the backs of the foot pegs.

Meanwhile, McGrath was in a smoother line and in attack mode (elbows out, head over handlebars).

Henry was understandably fatiguing; arm pump had affected his grip and the temperature that day reached 89 degrees. But he couldn’t relent; he battled with not only his teammate, but the championship points leader.

Henry had won the previous round at High Point Raceway a few weeks earlier, his first career win in the premier class of AMA motocross. Beating McGrath meant taking over the points lead. Hanging off the back of the bike while simultaneously rolling on the throttle with his fingertips, Henry’s last resort was to get his foot on the rear brake to slow himself down.

John Dowd’s Boot

If only he hadn’t been wearing John Dowd’s right boot that day. Henry tweaked his ankle in practice two days prior and it hurt so badly that he borrowed a size 11 boot from his friend Dowd. It was one size too big, which he needed to accommodate for his swollen ankle. He also asked Honda tech Cliff White to fit a steel plate to the insole.

It was the flexing of the boot’s sole caused him the most pain, and the plate eliminated that flex, including this moment when he really needed it to reach his rear brake.

The last thing working against Henry was his own bike setup. In normal conditions his CR250 was perfect for his riding style, a shorter front end with more weight bias and a looser rear shock. Tall and lean, Henry didn’t like too much rebound in the shock.

According to Dave Arnold, Honda’s team manager in the 1980s and early to mid-’90s, the looser damping, lesser rebound, and amount of speed and torque a factory Honda could produce was lethal in that specific moment on that specific track obstacle. A different bike setup wouldn’t have saved Henry from flight, but he may not have flown as high or as far.

Everything happened in reverse for Doug at that moment. Everything happened that you didn’t want to happen.

–Dave Arnold

“Everything happened in reverse for Doug at that moment,” Arnold says. “Everything happened that you didn’t want to happen.”

The one thing that did go correctly for Henry was his decision to stay on the bike. He debated letting go upon takeoff. Once the decision to stay on the bike was made, he then thought maybe he could make it to the retention pond in the infield.

“[I thought] that [would] be a soft landing, not realizing I was only a quarter of the way there,” Henry says. “I decided to get control of the bike and just land it and see what happens. I remember going off that jump in the air and it was like one of those dreams. It wasn’t real. I’ve always had dreams where I’m riding and I land and I wake up. It really felt like that. It was really just a dream.”

I remember going off that jump in the air and it was like one of those dreams. It wasn’t real.

–Doug Henry

2.8 Seconds to Legend

But it wasn’t a dream. Once airborne, he pulled his body weight forward. With the front end high, he looked like Evel Knievel jumping the fountains at Caesar’s Palace. After 2.8 seconds of airtime, Henry’s rear wheel touched down first, about 20 feet shy of reaching the corner at the bottom of the hill.

To this day, LaRocco claims that he saw Henry’s shadow and thought to himself, “What is he doing?” The sprinklers at Budds Creek are spaced 60 feet apart and Henry came down next to the third one from the top. He traveled more than 120 feet downhill, nearly to the flatbottom. Beasley has since had the land surveyed and discovered that the vertical height of that track obstacle is 112 feet.

When the front wheel slapped to the ground, Henry’s body violently slammed into the seat; his torso folded completely in half and his head drilled into the front end. His right arm blew off the handlebar and got tossed out and behind him as if winding up for a pitch.

The force of the impact was so great on the bike that the load transferred from the suspension and into the bolts that held the shock into the frame. Cliff White said the bolts bent and had to be beaten loose from the frame. Surprisingly, the wheels were intact.

When the suspension rebounded, Henry’s body sprang over the front end and he did a forward somersault with the motorcycle. It was like he was wrestling his bike to the ground. His hands were tangled in the flailing bike, which knocked him in the head.

When he finally stopped rolling, he immediately took off his goggles with his left hand, paused, evaluated himself, realized that he could move his legs and feet, and then tried to roll onto his back. A sharp pain sent him back to his side.

Stacey’s Intuition Saves Doug’s Career

His spine bent so far on impact that his L1 vertebra burst, causing spinal-cord compression. Doctors later said the fact that he retained full movement in his legs was ‘miraculous’.

At the first hospital, when Stacey Henry asked a doctor to explain the surgery they were going to perform, he said, “You wouldn’t understand.” She handed him a piece of paper and a pen and asked him to draw it. He drew a crude stick figure that didn’t explain much.

He’s young, he can find another job.

–Doctor at St. George’s Hospital

“He’s young, he can find another job,” Stacey remembers a second doctor telling her. She knew she had to get Doug out that hospital.

“How he dismissed all the hours and heart this guy had, I thought, ‘He has no clue what this guy’s been through,’” she says. “He thinks it’s just a backyard accident.”

Stacey moved her husband to George Washington University, where a young neurosurgeon named Charles Riedel partnered with an orthopedic surgeon to clean up the bone fragments that lay dangerously close to the spinal column. Then they rebuilt Henry’s L1, a new procedure at the time.

“In place of that vertebra, we then placed a titanium mesh cage, which we filled with grafted bone so it would grow and replace what used to be there,” Dr. Riedel says.

Had the two doctors at the first hospital been more compassionate and empathetic, Stacey Henry today believes that she would have allowed them to perform a more traditional and safer operation. Rods would have fused six to seven vertebrae together. Henry’s career as a professional motocross racer would have ended.

The Legend of Doug Henry

As emergency responders knelt near Henry’s head in the Budds Creek dirt, trying to ascertain the location of his pain, the rider struggled to remove his gloves. He pulled off his left Fox Pawtector, which revealed a gold wedding band. Henry didn’t remove his ring, even while racing. Exhausted, he stopped moving and rested in the fetal position while the EMTs and Honda staff worked to stabilize him.

When a transport vehicle wasn’t able to get into the valley to drive Henry up to the ambulance, four EMTs and two Honda team members picked up the stretcher. With his legs and torso taped down, his neck in a brace, his jersey cut off, and his mouth smothered with an oxygen mask, they carried him right back up the very hill that dropped him from the sky, now called Henry Hill.

Maybe it was at his request, maybe he wrestled them loose, but Doug Henry’s arms were free. When he raised his two bare arms into the air and held a double thumbs-up, the swelling crowd at the fence knew they were witnessing a legend.

If you loved this article, you’ll also love “Doug Henry and the Dam,” an origin story about the track that made Doug Henry, well, Doug Henry.