The Curious Life of Terry Pratt

By

The quirky story of an American motorcycle journalist who put his life on pause to spend 6 months following the MXGP season. 35 years later he published a book of his travels.

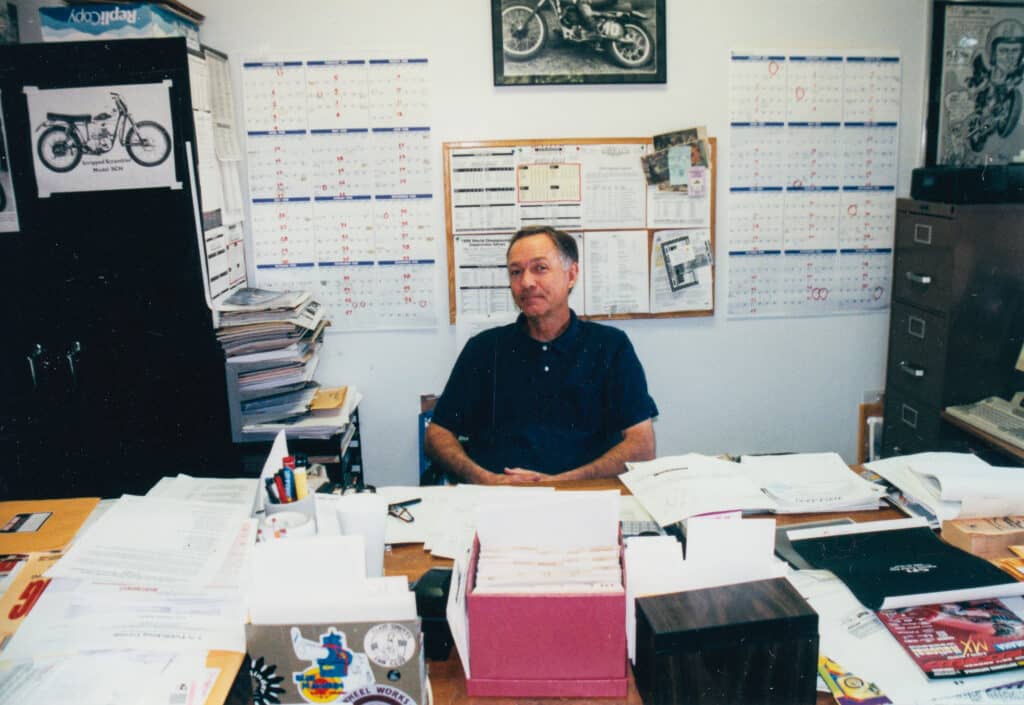

The box of cards sat on his desk at “Cycle News” for over 30 years. Nobody remembers them not being there. The desktop computer didn’t replace them. Nor did the Palm Pilot, the BlackBerry or smartphone. It wasn’t even as sophisticated as a Rolodex system. It was just a plastic box of white cards, each 6-in. x 8-in., the type your grandmother used to keep track of her recipes.

It was on brand for Terry Pratt.

This was how Pratt cataloged his client, contact and account information during his decades as an advertising manager in the powersports industry. If Honda or Suzuki or Yamaha won a race on Sunday, he’d thumb through the alphabetized dividers on Monday morning, pull out the card he needed, and call that OEM about placing a win ad.

When an account changed–an employee shift, an office move–he inserted the card into a typewriter and tapped out the new information. The cards of his oldest accounts were covered in ink and scribbles. He did it that way his entire career.

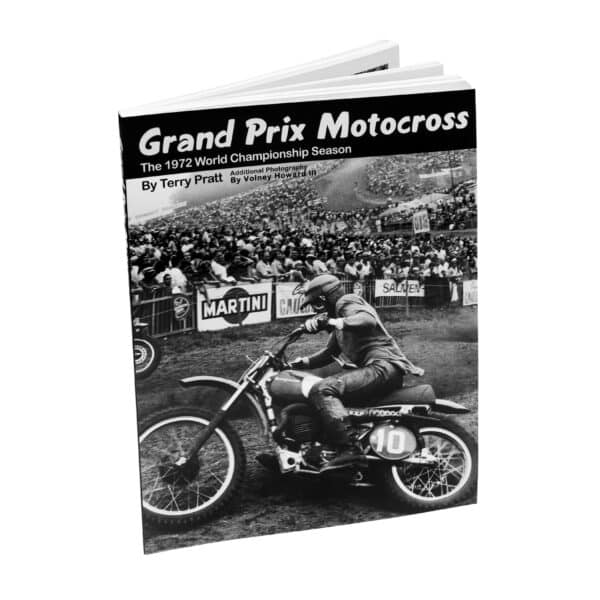

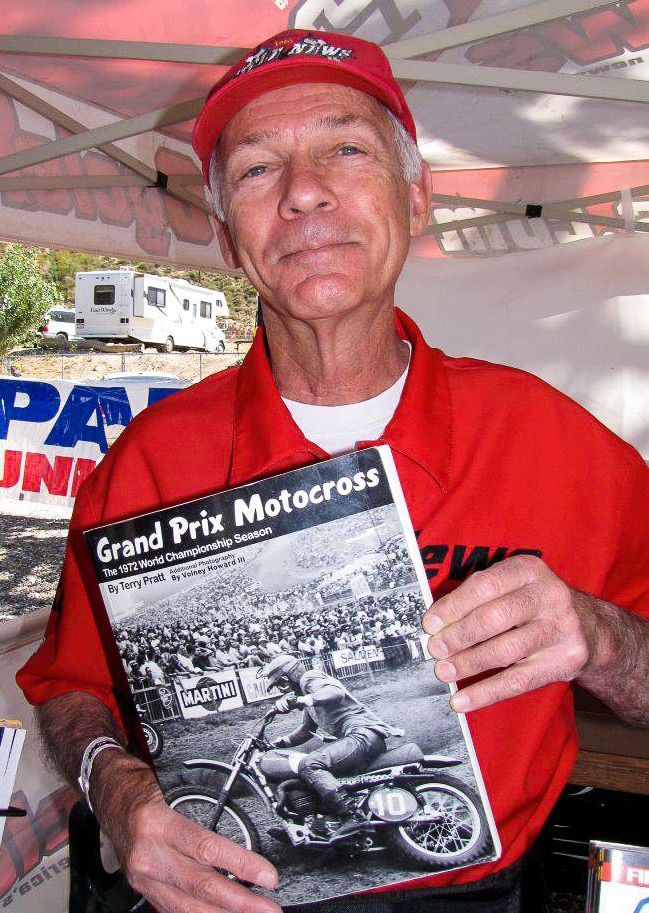

Grand Prix Motocross Book

Pratt wasn’t afraid or skeptical of technology; he worked on computers for the Army in Heidelberg, Germany from 1966-68. He simply had his own ways of being effective. And he clung to his habits, such as the regimented way he managed voicemail.

“Hi! It’s Terry Pratt. It’s Friday, the 6th of September. I’m going out for lunch right now and will be back in the office on Monday, September 9th.” In all his years in the working world, Scott Cox never met another person who made daily voicemail message updates, letting callers know exactly when he could (and couldn’t) be reached.

Cox bought media for his clients and worked often with Pratt. “He was an old school ad guy,” Cox said. “He made himself available and details were very important to him. And he was a human touch kind of guy. He’d send a letter, note or card or just pick up the phone and call. He was a very easy guy to say ‘yes’ to.”

Pratt’s uniform came straight from an Eddie Bauer catalog and he refreshed it once a year (solid green and red shirts, khaki pants). He had a go to blue blazer for conventions and banquets. He preferred his beers on the warm side, and when the bartender at American Legion Post 555 saw him coming, he’d pull a few Heinekens from the cooler and set them on the counter.

Staunchly grounded in his aversion to email, his co-worker Rhonda Crawford sent messages to clients on his behalf when the communication option became impossible to ignore. Eventually, to the amusement of his friends and clients, he caved.

When he saw an email signature with contact info at the bottom of a message, he’d print it, cut it out, and tape it to the appropriate contact card in his file box.

A lifelong bachelor, with no kids, Pratt mostly ate out of the house. The glass of milk he ordered with every single meal sat untouched until he cleaned his plate. Then he picked it up and–glugglugglugglug–downed the entire glass in one shot. When he set the empty glass on the table he wiped his mouth and said, “Ahhhhh” with exaggerated satisfaction.

Friends recall him as being generous but tight with his money. He wrapped gifts with the pages of leftover issues of Cycle News. At potluck dinners, he’d find out in advance who committed to the laborious process of making the chili and volunteered to bring the Fritos. He loved Fritos in his chili.

His refrigerator stayed empty, his living room had more motorcycle frames than pieces of furniture and he used his oven to heat up cylinders for curing paint or to make piston insertion easier.

The garage was the tidiest room in the house. Another co-worker, Mark Thome, said Pratt could have been the perfect case study from Dr. Thomas J. Stanley’s 1996 best-selling book “The Millionaire Next Door.”

Terry Pratt’s Lifelong Project

But one habit that he strayed from, that every motocross fan is thankful for today, is when he stopped talking about the book he wanted to write and just did it.

It only took 35 years, but in 2007 he finally finished it; Terry Pratt published “Grand Prix Motocross: The 1972 World Championship Season,” a 241-page, two-and-a-half-pound coffee table tome filled with more than 300 gorgeous photographs accompanied by race reports and observations.

In this large format book, Pratt’s attention to detail shines. His viewpoints and curiosities about the sport, the technology and its characters make for an enriching read and a worthwhile history lesson on a remarkable time in racing.

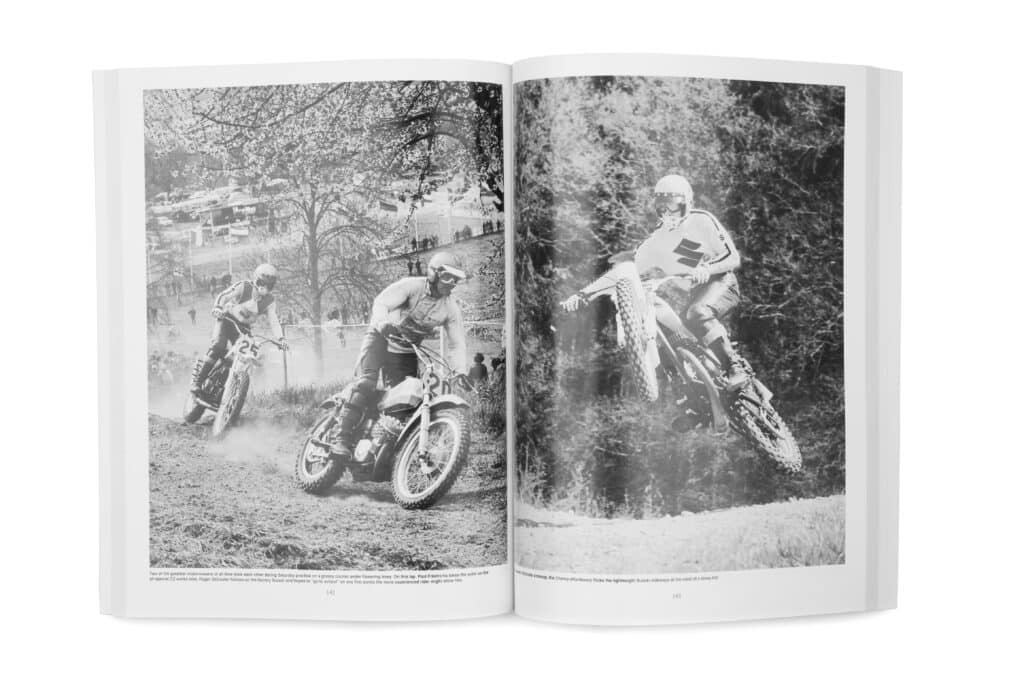

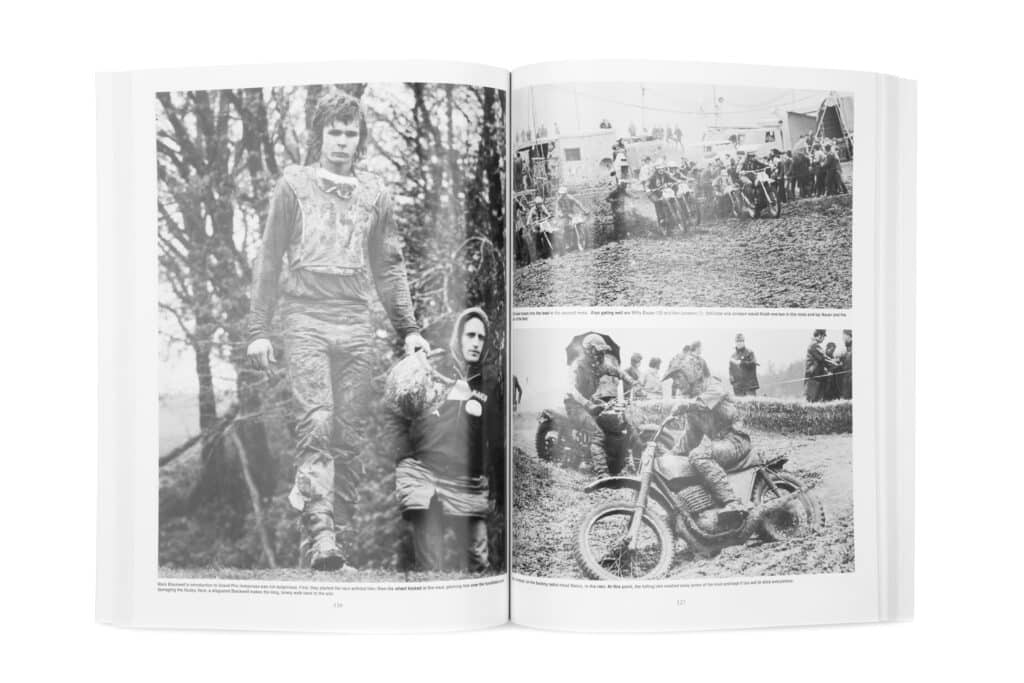

In 1972, the technology arms race between the factories shifted gears big time. Roger De Coster successfully defended his first 500cc crown and was on his way to earning the label “The Man”. Joel Robert won his sixth and final 250cc title. And several Americans, including Mark Blackwell, Bryan Kenney and Billy Clements competed in the 500cc class.

For 35 years it stayed in his head and he wanted to–had to–get it out. He gathered his notepads and race reports, his prints and negatives and finished the last leg of a journey he started in March 1972. With help from the “Cycle News” production department, Pratt finalized “Grand Prix Motocross”.

Buy Grand Prix Motocross in The Shop

Nobody remembers the number of books published or sold. But Kathleen Conner, who worked in CN’s production department, remembers seeing the first physical proof. The text came out of the manual typewriter that sat on Pratt’s desk. He printed the photos and cut and pasted them onto 9-in. x 12-in. pieces of paper.

“We had to retype everything and put it together digitally. That guy was such a character.

–Kathleen Conner

Pratt died in April 2012 and the book he left behind, that he spent over half his life making, was believed to be out of print and unavailable. Copies occasionally popped up on Amazon or eBay for far more than the original $39.95 retail price. In June of 2019, Terry’s unsold stock resurfaced and We Went Fast committed to finishing what Pratt started. Supply is limited and it will never be printed again.

But first, more on the curious life of Terry Pratt.

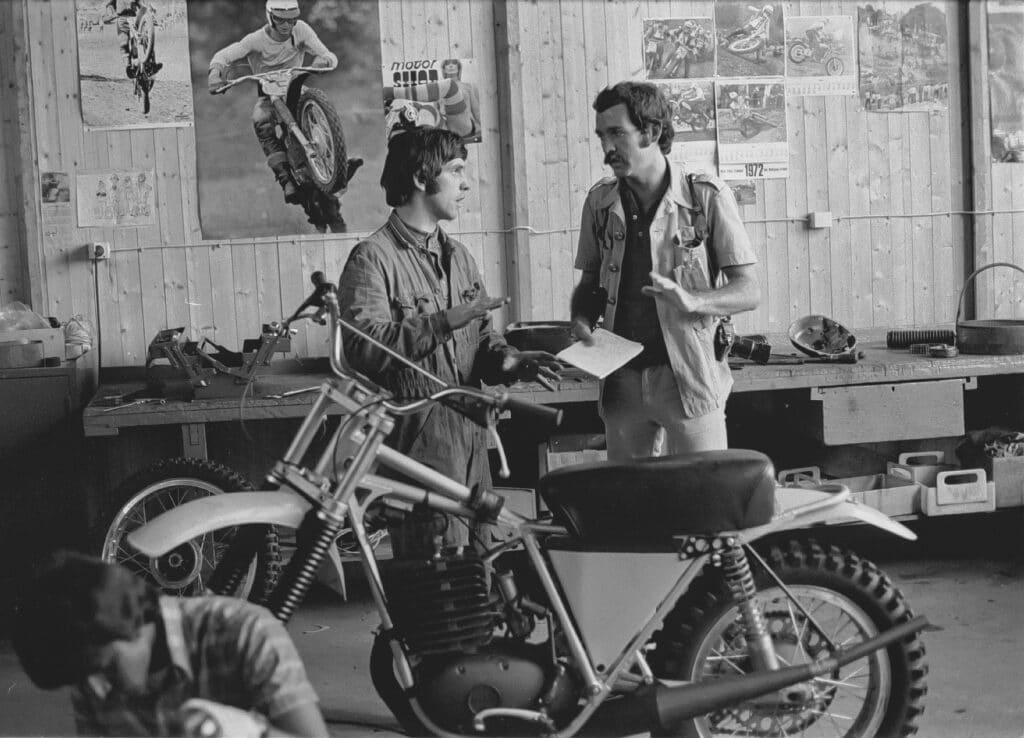

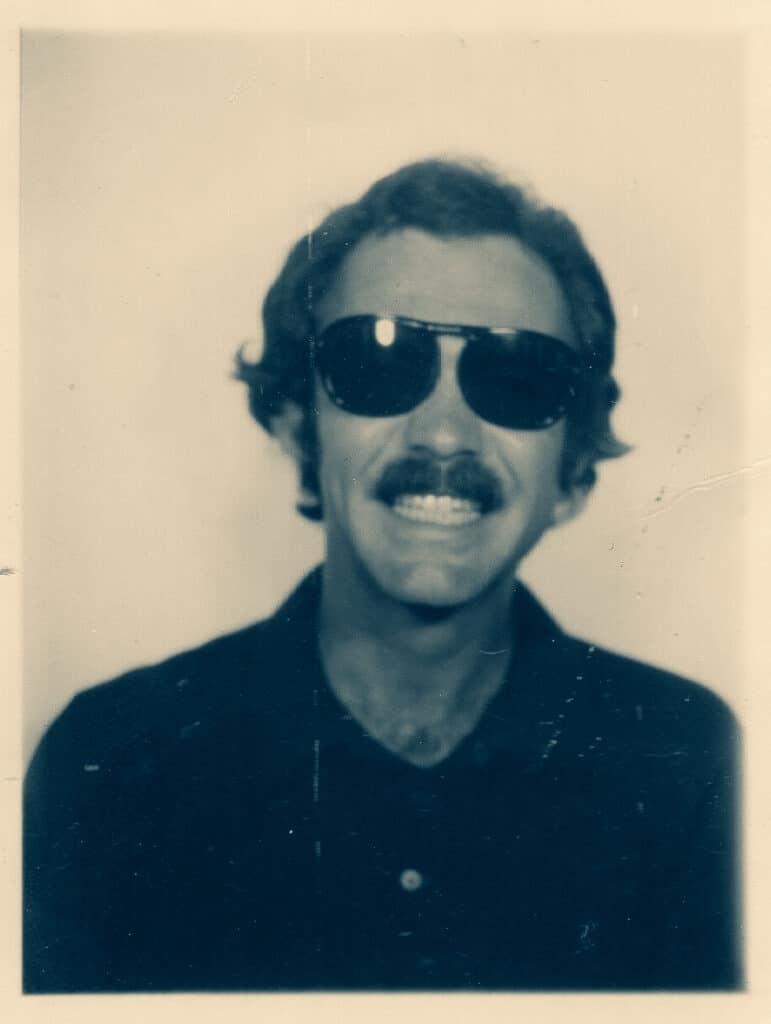

Terry Pratt, Young Journalist

Terry had a knack for observation, wit and storytelling. He had a thorough and resourceful style and took meticulous notes and used the white space on anything in his pocket in the moment, a hotel notepad or a letter from home. He roamed the paddock and snapped photos, asked questions, and stood back quietly while scenes like the above unfolded in front of him.

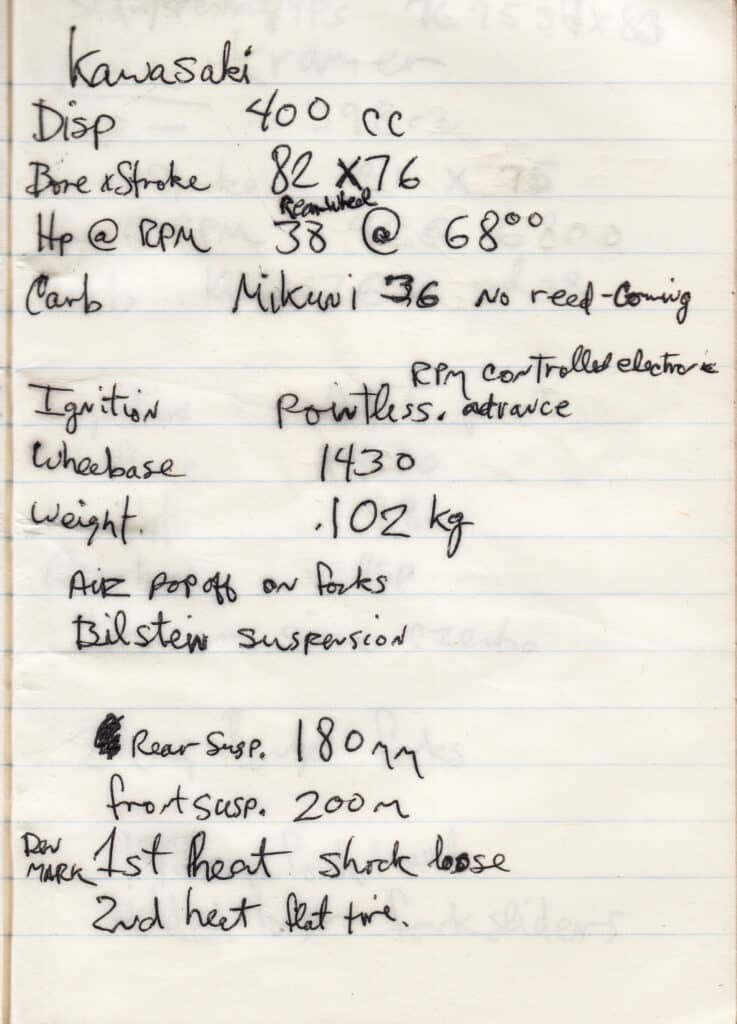

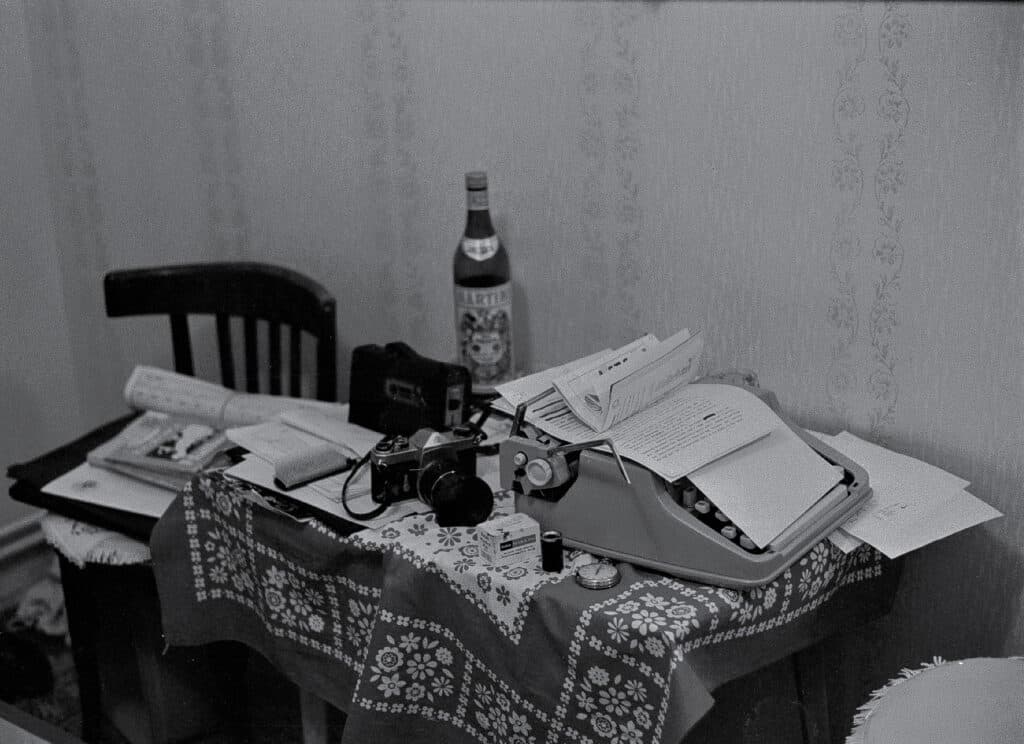

Pratt wrote down every technical piece of information he could find out about the motorcycles; he tracked brand of ignitions used, horsepower, bore/stroke measurements, bike weight, wheelbase, and so on. He carried an analog stopwatch to track practice lap times, he logged crude lap charts during the motos and wrote down the home addresses of the riders he covered.

Around his neck hung a Pentax SLR with Takumar screw-mount lenses. He used Kodak Pan Plus-X film, which he developed in hotel room bathtubs. At campgrounds he used a sink and a change bag.

The habit of working with what you had, when and where you had it probably came from his father, John. Educated through the 8th grade, John Pratt lied about his age and joined the Army during World War I.

At 16, he went to France where he managed the horses and mules that carried heavy artillery. He also served in the Army in World War II. At home, John drove trucks for the borax mines in Boron, California and used the idle time waiting in line to load or unload for writing and inventing. He once won a Golden Hammer Award from “Mechanix Illustrated”, but didn’t land any patents that made him enough money to quit his job.

Terry’s mother, Barbara, moved to Boron during the early years of The Great Depression. She was 12 and the mines provided reliable work for her step-father, Vern. In 1941, at the age of 21, she became the mining town’s postmaster. She met John, 22 years her senior, while working at the post office. After his discharge from the Army, they were married.

Terry arrived in March 1945, followed by Bill two years later and a sister, Shelley in 1954. Bill died of stomach cancer at the age of 7 and Terry spent a year holed up in his room reading the encyclopedia, which undoubtedly contributed to his lifelong thirst for knowledge. Shelley said Bill’s death wasn’t talked about much and she didn’t even learn about it until many years later.

The same year Bill died, Rick Richards moved to Boron and rented a home owned by the Pratts. Terry went with his mother to settle the paperwork and bonded with Richards through talk of sports cars and engines. In their freshman year of high school the band teacher, Don Wilcox, picked up a secondhand Sears All State.

Support Story Telling!

“That was the first bike Terry and I got to be around,” Richards, now 75, said. They even got to ride it and the BSA Wilcox later bought. That same school year, Clyde Alexander, the school’s woodshop teacher, sold Pratt a 200cc Dot. They borrowed Terry’s grandfather’s pickup truck to get the bike. Neither kid had a driver’s license but that didn’t stop them from attending District 37 Hare & Hound events to race and spectate.

He went to college, first in Ventura, then Bakersfield. His grades were poor and when the Vietnam War heated up in the mid-1960s, he and his roommate figured they were probably going to flunk out and get drafted so they enlisted in the Army. He wanted a post in journalism but for reasons nobody remembers (or never knew) he wound up doing programming in Heidelberg, Germany from 1966-1968.

In his later civilian years, he shunned computers, citing them as the eventual death of print media. Pratt didn’t come home during his leave periods. He traveled around Europe instead. Richards believes this was when Terry first experienced international motocross races.

After discharge, he served in the reserves from 1968-1972. He lived in Long Beach but then “chased a girl” up to San Francisco, according to Richards. Shelley remembers him working for a bank, trying to make use of the skills he learned in the Army but did he didn’t like it and detested the cooler weather even more.

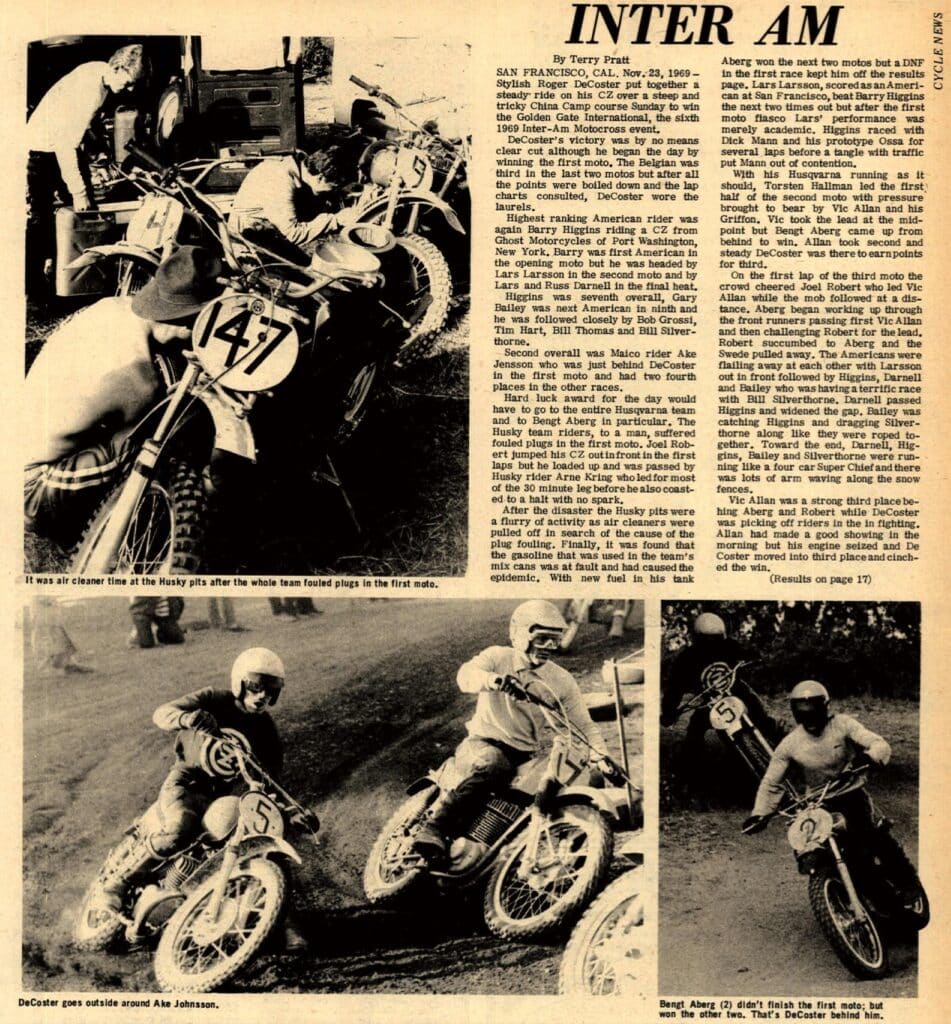

Pratt returned to Long Beach and in 1969, became a stringer for “Cycle News”. He also built relationships at the monthlies, now defunct titles, such as “Cycle Illustrated” and “Dirt Cycle”. He penned how-to articles about wrenching, riding and safety gear, wrote bike reviews, previewed competitions and earned a regular department column he called “Prattle.”

One of his first articles for CN was about De Coster’s San Francisco Inter-AM win at China Camp in November 1969. De Coster went 1-2-2 on his CZ. Races like these likely gave Pratt the urge to get back to Europe again and report on the GP riders in the most prestigious motocross championship in the world.

MXGP Bound

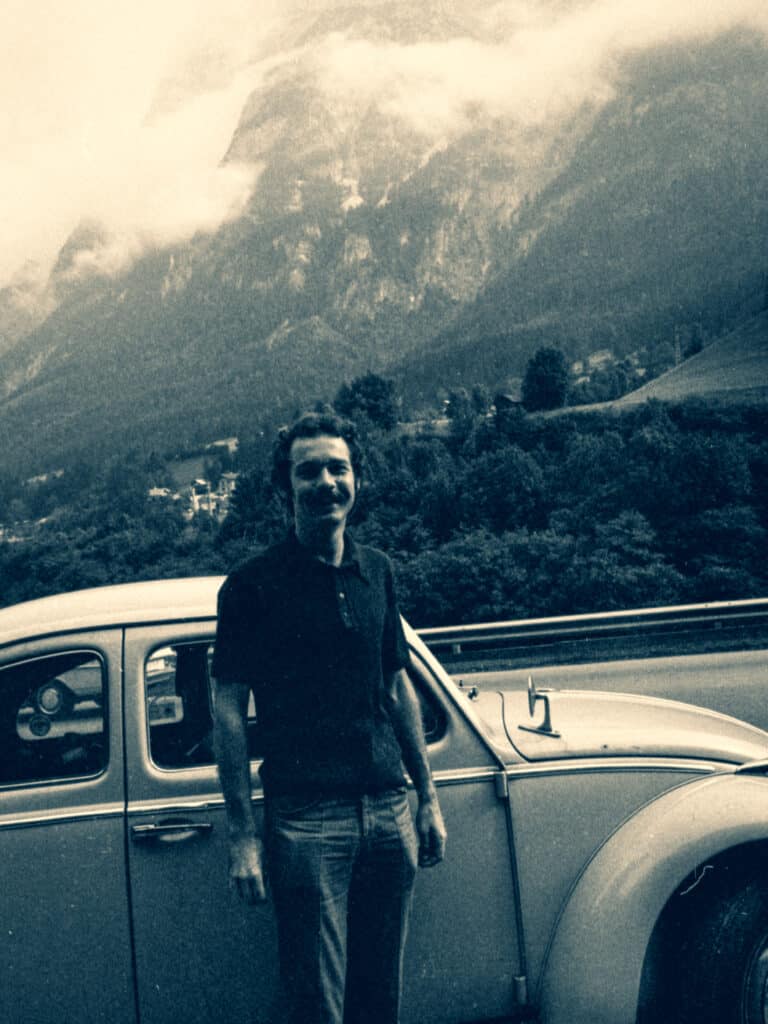

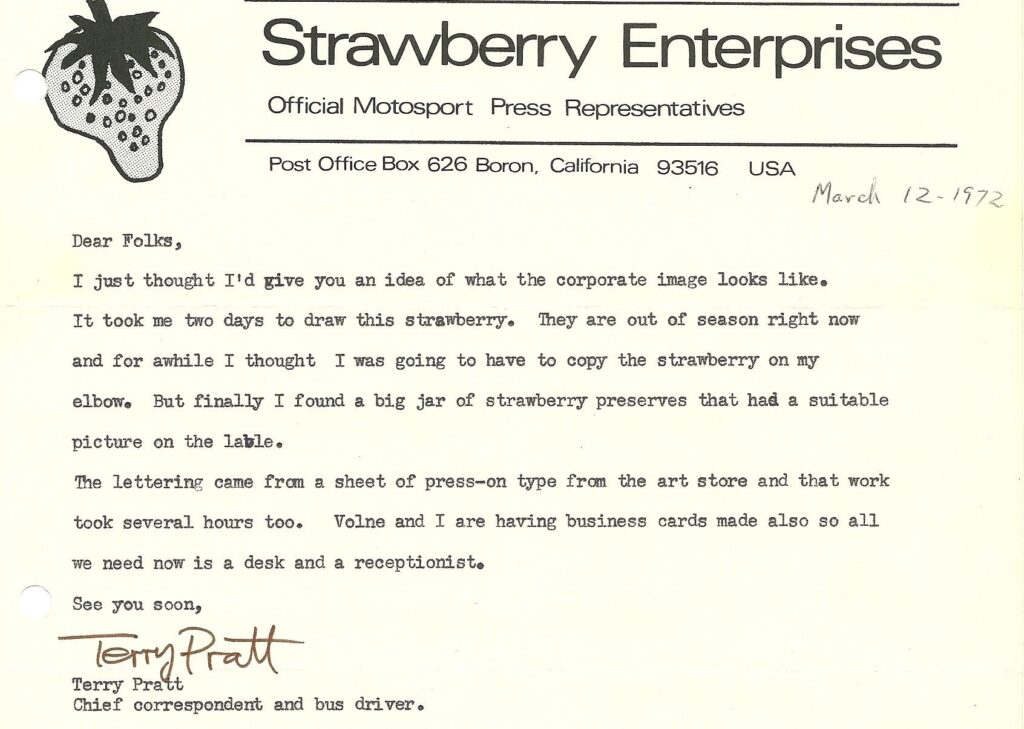

In March 1972, just before his 27th birthday, Pratt formed Strawberry Enterprises “Official Motosport Press Representatives”. That was the name he gave his freelance writing business. The strawberry referred to the scrapes, rashes and skid marks riders get on their elbows and knees from wiping out. Pratt and a friend named Volney Howard III were headed to Europe as American correspondents in the World Motocross Championships. He sold his car and asked his teenage sister to housesit.

In hindsight, you could say Pratt had poor timing. Motocross racing in the United States surged in popularity in 1972. The movie “On Any Sunday” made its way around the country from the previous summer’s theatrical release and enjoyed another boost in attention when The Academy nominated it for an Oscar in the Best Documentary category.

The first official (stand alone) AMA Pro Motocross Championship series started that March. And in southern California, a cocksure rock promoter put on one hell of a mid-summer show; Mike Goodwin brought motocross into the LA Coliseum.

Or, it was great timing. As Pratt points out in his book, “the 1972 Grand Prix season marked a turning point in motocross history.” European brands still dominated the results sheets but Yamaha joined Suzuki in the 500cc GP record books.

The Japanese brands had started a development wave so powerful that the FIM changed the rules for 1973. Minimum weight restrictions were enforced and 1972 marked the final opportunity to see full titanium frames, carburetors made of magnesium and 500cc machines that weighed under 190-lbs.

Joel Robert and Paul Friedrichs were at the end of their legendary careers, De Coster and Heikki Mikkola still close to the beginning. And pioneering American riders made their first international dent in the domination of European athletes on their own continent.

Pratt left for Europe with a few 100-ft. rolls of film, a cassette loader, his Pentax, four lenses and enough money to buy a Volkswagen Westphalia camper. After 12,000 hard miles, it blew up one night on the Autobahn. Volney also shot photos and his photography appears in the book.

I remember that I liked both of those guys and they were really cool. They were easy to do an interview with. Some (journalists) were a pain in the butt. I know I felt different about them two guys. I liked their style of writing and looked up to them with respect.”

–Roger DeCoster

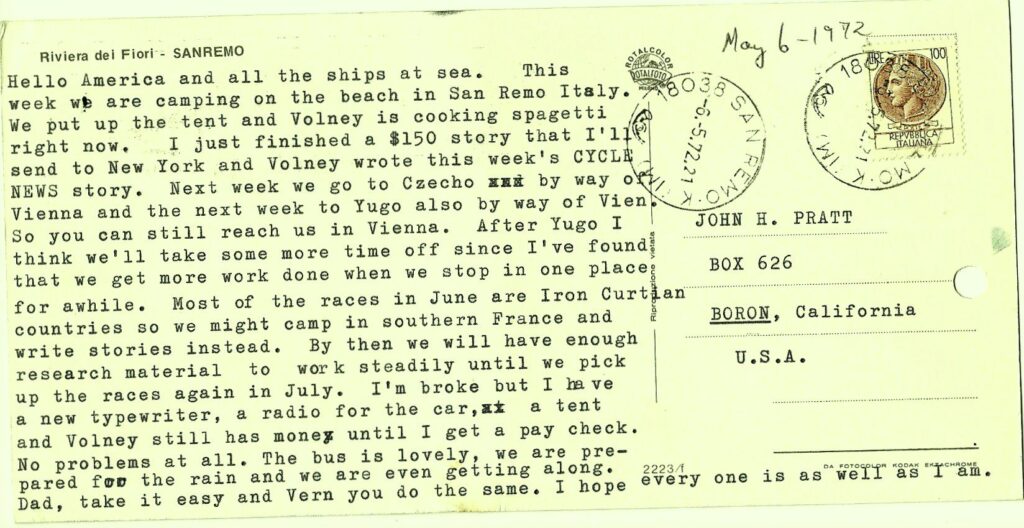

Pratt visited the homes of the riders, the Maico factory, the Husqvarna factory, international races outside of the MXGP season and filed articles and photos to publications back in the States. On May 6 he sent a postcard home from Italy. He and Volney camped on a beach in Sanremo.

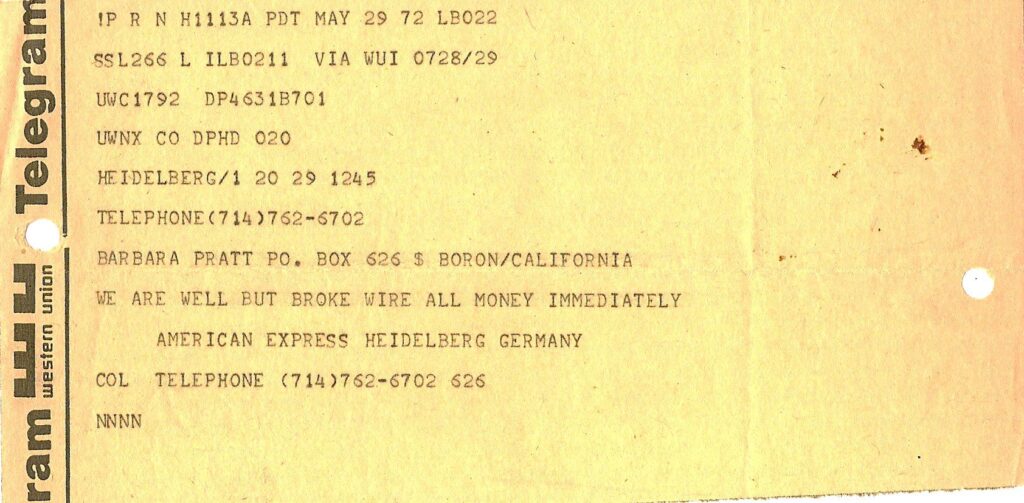

He said he was “broke but I have a new typewriter, a radio for the car, a tent and Volney still has money until I get a paycheck.” From there they drove to the 250 GP in Czechoslovakia. On May 29, from a Western Union in Heidelberg, West Germany, he sent a telegram home to his mother: “WE ARE WELL BUT BROKE. WIRE ALL MONEY IMMEDIATELY.”

For unexplained reasons, Pratt and Volney missed several GPs in May and June. They skipped the 250 GPs in Yugoslavia and Poland, the 500 GPs in France and Czechoslovakia and both GPs in Russia (one of them conflicted with the W. German 250 GP). Maybe money troubles caused their absence. Or maybe their one trip behind the Iron Curtain for the 250 GP in Czechoslovakia rattled them.

Pratt endured a stressful border crossing. He told his friend Rick Richards that he sat for hours with a cocked M-60 machine gun pointed at his head. “That really upset him,” Richards said. “But he said the people on the other side of the border were really nice.”

In the book he writes about the Russian tanks rolling into Prague in 1968 and how they never left. At a party he spoke to a Czech soldier and got him to admit that “because he was in the military he had to say he liked the Russians. Then he patted his heart and said that none of the Czechs had any love for the Russians in general.”

Forever 1972

After the Trophée des Nations in Genk, Belgium in September, Pratt returned home and continued to file stories for motorcycle magazines. He went back to Europe in the summer of 1973 and covered Brad Lackey’s first year on the 500cc World Motocross circuit. In 1974 he worked on behalf of Husqvarna East in Lorain, Ohio. His mission consisted of writing race reports and sending back technical information on the bikes to the dealers in the United States.

In a letter to Brad and Lori Lackey dated May 16, 1974, (he kept photocopies of letters to his editors, athletes, etc.) Pratt said, “I’m going to spend the summer having a good time and watching you score lots of points, Brad. With a little luck, maybe I can score a few points myself if you know what I mean.”

If only typewriters had blush-face emojis.

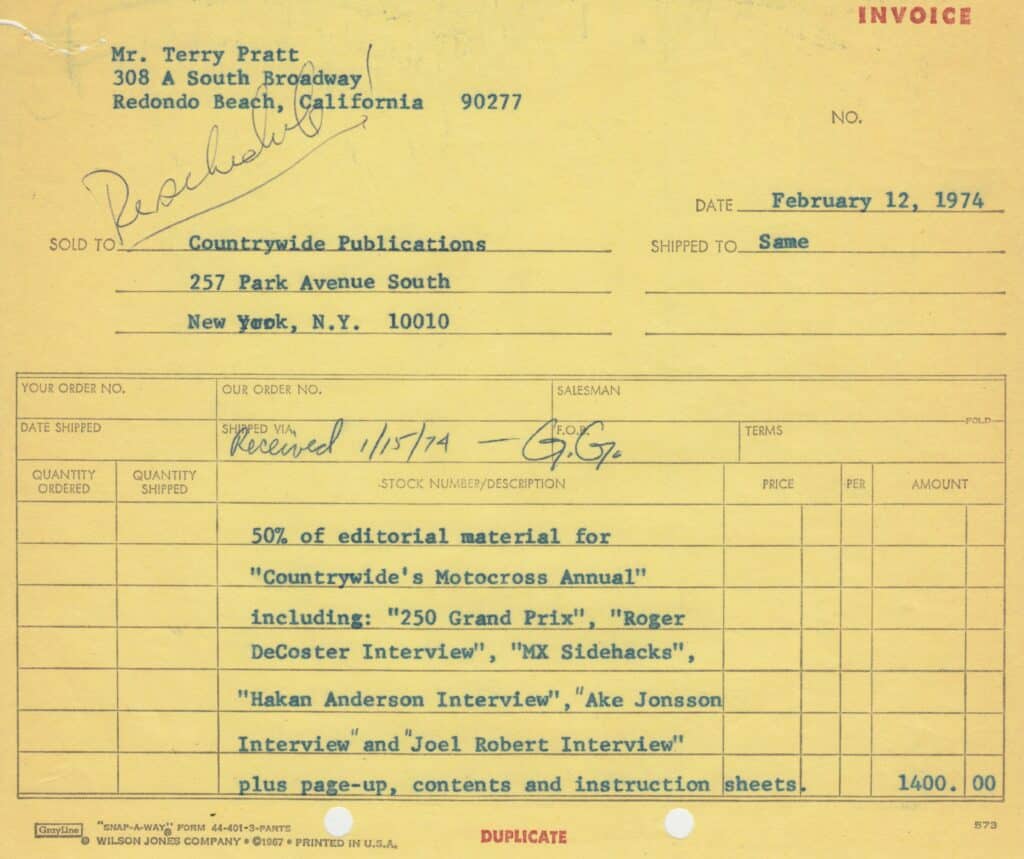

According to other papers found seven years after his death, evidence of plans for a ‘Motocross Annual’ surfaced. Pratt had sold Countrywide Publications (publishers of “Cycle Illustrated,” “Dirt Cycle,” and “Motorcycle World,”) on the idea of a ‘one-shot’ magazine.

The special issue, about the 1973 World Motocross GP season, was slated to feature season reviews and exclusive interviews with Roger De Coster, Joel Robert, Hakan Andersson and more. Pratt built an outline, typed and submitted the stories, and even sent in a $1400 invoice, half of the agreed upon final total. After inflation, $2800 equals over $15,000 in 2019.

The annual never happened, the $1400 never got paid. Pratt went back and forth for months with his editor Gregory J. Gore. Gore’s publisher moaned of a paper shortage and told him they were “losing money on all these cycle books so…” The oil crisis ended in the spring of 1974 but fell in the middle of a stock market skid that saw the Dow Jones lose 45% of its value in a nearly two-year period. It was a bad time to sell almost anything.

Gore informed Pratt of the news in a letter dated March 26, 1974. The ’73 GP reviews were dead and the interviews were at risk of going stale because the 250 GP season started on April 7 and the 500 season April 21. The interviews were pieced out and published in 1974 issues of “Dirt Cycle” but not all of them went to print. Pratt kept the manuscripts and they’ll be used in a future We Went Fast feature, which is already in the planning stages.

While Pratt traveled around Europe in 1974, Barbara sent him a letter to inform him that he’d failed his test to obtain a real estate license. His career shift succeeded in the late 70s when he got an advertising gig at Hester Communications on their “Bicycle Dealer Showcase” magazine.

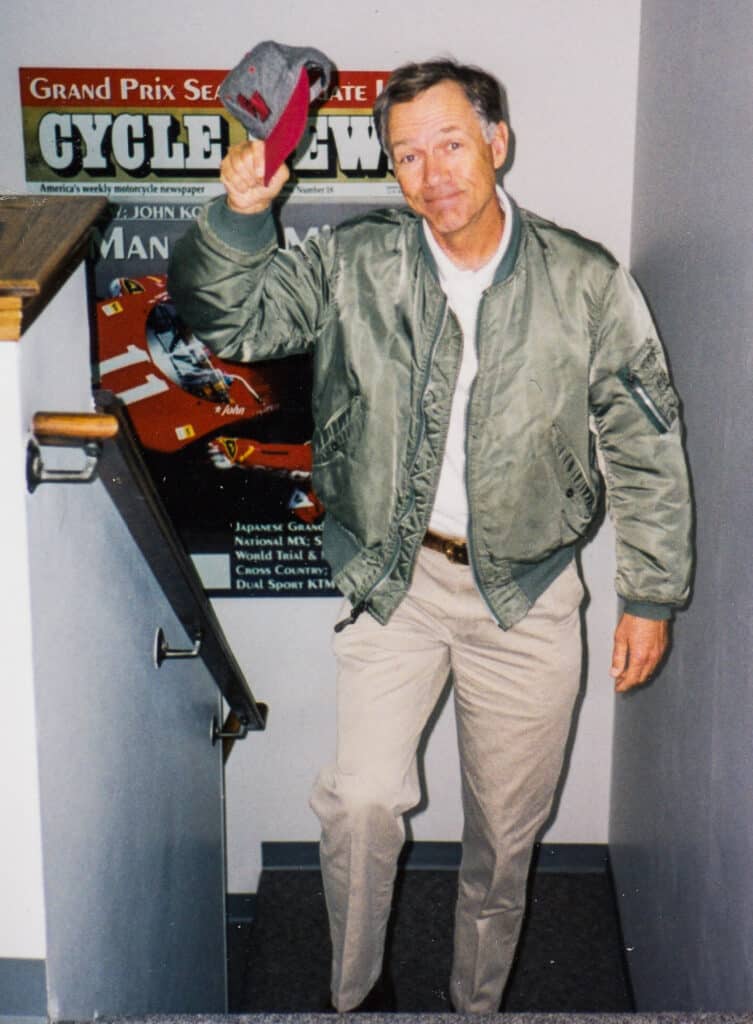

In 1979, Pratt re-joined “Cycle News” as a sales manager and ended his CN career 32 years later as national accounts manager. Through the 80s, 90s and 2000s, Pratt managed almost every OEM win ad that spread across the pages of “America’s Weekly Motorcycle Newspaper”.

On Any Sunday Swag by We Went Fast

Outside of ad sales, Pratt spent his free time trolling swap meets for parts to rebuild his growing stable of vintage dirt bikes. Vintage for him, however, was pre-1974. Pratt raced vintage motocross long before it became a vogue activity. He won regional and national championships.

In 1989 the California Vintage Racing Group joined the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) to form an entirely new member-owned national organization to promote historic racing. Pratt had influence in the deal and joined AHRMA’s first board of trustees along with racing legend Dick Mann.

While Pratt stayed busy selling ads, buying, restoring and racing vintage bikes, the contents of a file cabinet in his office tugged at him. The friends he met after 1972 like to say they can remember him “working on that book” for as long as they knew him.

Grand Prix Motocross Book

He spent a dozen years pecking away at it, on and off, with the CN production staff. “He chose his photos very carefully,” said Mark Thome. “Each one had something to say about the historical significance of the sport. Each photo almost tells a volume of a story.”

“Cycle News” laid Pratt off in 2011. That August Scott Cox helped Pratt launch a website to continue selling the seminal book. “I want to sell these books and I don’t care how long it takes to do it. And I’m not going to discount them!” Cox recounts Terry saying when he asked for ecommerce help.

In late February 2012, Pratt received a stage 4 pancreatic and liver cancer diagnosis. In March, a friend took him to get the ports inserted for chemotherapy treatments. He didn’t make it to the first appointment. Surrounded by family and friends, Pratt died at home on April 15.

Friends, collectors and enthusiasts bought up his motorcycles and parts. Julian Heppekausen, CEO of culture brand Deus Ex Machina bought Pratt’s last build, a 1966 Triumph T120 and raced it in events in Germany and France in 2014 and in the Mexican 1000 in 2016.

He credited the bike’s durability to Terry’s attention to detail and the careful manner in which he rebuilt all his machines. Among other classic models, Pratt also left behind four complete and period-perfect BSA Goldstars and a 200cc Dot, a similar version of the first bike he owned, which he was in the middle of restoring.

The rest of his motorcycle memorabilia, papers and photos got scattered to friends and collectors.

The books got left behind.

If you made it this far I will assume you enjoyed “The Curious Life of Terry Pratt”. I took great pride in telling Mr. Pratt’s story. I never met Terry but his reporting style attention to detail drew me in. This story was told through interviews with his remaining family and friends and personal effects I found from visiting Boron, California.