No Planes in the Sky: The Grounding of Team USA 2001

By

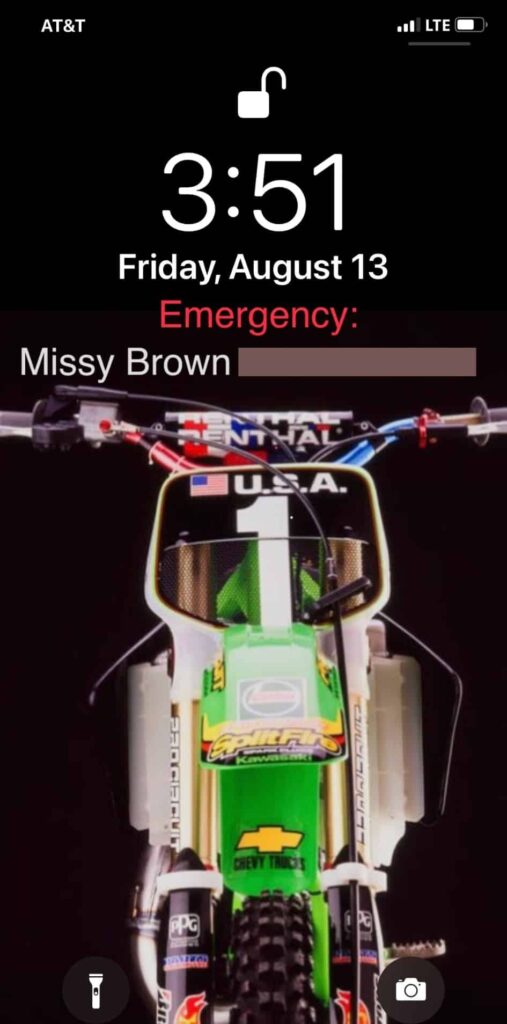

The home screen image on Mike Brown’s mobile phone represents the best and worst memories from his decades-long professional racing career. It’s a portrait-style photo of a 2001 Kawasaki KX125 taken in a Santa Ana, Calif. studio by Simon Cudby.

Across the top of the black vented number plate is a small American flag with “U.S.A.” next to it. A white #1 decal stretches downward and appears to sink into the green front fender. The handlebars show a bit of national flair, red on the throttle side, blue on the clutch side. The crossbar pad has three stripes on half and “motocross des nations” printed between the Renthal logos on the other half. The bar mounts, too, are split between red and blue. Too wide to fit in the screen space, the gray grips disappear off the edges.

Brown never rode this bike. This particular motorcycle was supposed to go to Belgium for the Motocross of Nations at the Citadel in Namur on Sept. 30, 2001. But he won the AMA 125cc Pro Motocross Championship earlier that month on a bike exactly like it.

Today, when Brown sees his unused Team USA machine on display in the showroom of Pro Circuit’s Corona, Calif. headquarters, he doesn’t sit on it. He even owns a spare set of those handlebars and mounts. But he doesn’t use them. Even though the image on his phone, which he sees every single day, is a sore spot in his life, something that represents “the most disappointing thing I’ve ever had happen in racing”, he still chooses to make it a part of his everyday life.

It’s his way of saying he’ll Never Forget.

Part 1: Where They Were

For those involved in this story, and for most reading it, the morning of September 11, 2001 began unremarkably. As any Tuesday in early September might.

Even the President’s Daily Brief included nothing alarming. It was heavy on matters in Israel. George W. Bush woke up in Sarasota, Florida and planned to spend his morning at an elementary school pushing his “No Child Left Behind” education initiative. At breakfast, the White House Chief of Staff, Andy Card, remembers saying to the president, “It should be an easy day.”

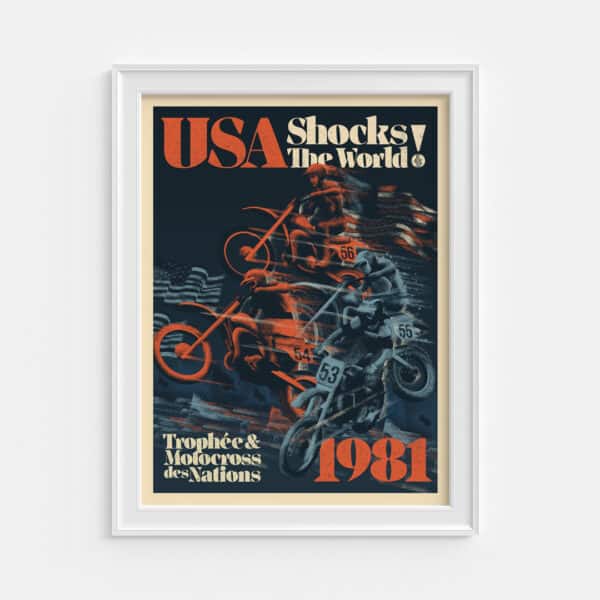

MXoN Artwork from We Went Fast

The dozen or so people involved with Team USA for the Motocross of Nations could have said the same thing. An easy, routine day. The AMA Pro Motocross Championships finished nine days earlier. Teams assessed their losses and victories. Some riders prepared to switch brands and everyone looked ahead to the already too-close 2002 season. In 19 days, Team USA would defend its title at the 55th running of the Olympics of motocross. All three riders – Mike Brown, Kevin Windham and Ricky Carmichael – lived east of the Mississippi River but Carmichael and Windham were in Southern California for bike testing with Honda and Suzuki on Sept. 11. Brown had just returned from California. He was at home in Tennessee.

When American Airlines flight 11 hit the North Tower of the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m. Eastern time, Carmichael stirred from sleep in the guest room of a home in Laguna Niguel, Calif. With a ‘wheels up’ departure of 6:30 a.m. Pacific time, he tried to orient his mind for the long day ahead. He was brushing his teeth when he heard his friend and mentor Johnny O’Mara yell from the living room.

On the other side of the Santa Ana Mountains, in Corona, Calif. Dottie Windham’s phone rang. Her sister wanted to know where she and Kevin were and if they were ok. She told Dottie to turn on the TV.

Brown was alone that morning. He worked on his motorcycle in the basement. His mother called. “Did you see what happened?” she asked. He had to walk upstairs to turn on the small television he and his wife kept in the kitchen. He didn’t understand what he saw. “Why would this happen?” he asked himself.

In 2001, nobody had news feeds in their palms or notifications on their wrists. So everyone involved with Team USA, almost all of whom were in the Pacific time zone, found out through their habitual routine of turning on televisions and radios first thing in the morning. Or because someone called them and told them you have to turn on the news now.

That’s how I found I out. My hotel room phone rang. I was in California, too, working for ESPN’s “MotoWorld.” That weekend we planned to produce the TV coverage of the RM Cup at Glen Helen Raceway. In a dark room, I watched what appeared to be a war breaking out in my own country.

Suzuki’s Lee McCollum used his television as an alarm clock. It came on every morning, automatically. “As soon as I opened my eyes I saw the towers collapsing,” he says. “I didn’t know what was going on. It didn’t sink in for a while that I was watching something real.”

At Pro Circuit, Jim “Bones” Bacon was a bit surprised to find the doors locked and the lights off. He arrived every morning before the start of business but usually someone was already there. When he opened the door to the race shop the “Bat Phone” – a separate phone line that few people have the number to – rang. It was Ted Studley, a freelance designer who produced the company’s ads and catalogs. He said something about New York City getting bombed.

Nothing Studley said made sense to Bones. “What are you talking about,” he remembers saying into the receiver. Pro Circuit didn’t have a television at the time. Bones turned on the radio. Even at the highest levels of government, nothing made sense. By 9:42 a.m. EDT, all 4,500 planes flying within United States air space had been told to ground immediately. A threat to Air Force One came around 10:37 a.m. and then a report of a car bomb at the State Department at 10:55 a.m. Both were false. The president demanded to be taken back to Washington but those bound by federal law to protect him refused his wishes until they could ascertain more information.

That chaos led McCollum to lie in bed far longer than normal. Honda’s Mike Gosselaar was about to get into the shower when his wife yelled for him. Pro Circuit’s Mitch Payton had just gotten out of the shower when he saw what he thought was a preview for an action movie. Photographer Simon Cudby caught a bit of the news before he left for his studio to shoot products for Mechanix Wear. He listened to the radio while he snapped images of gloves, thinking the entire time “What the fuck…”

Brown’s mechanic, Stephen Henderson, got roused awake by his roommate. Windham’s mechanic, Alley Semar woke up in the same house as Kevin and Dottie. Watching the news coverage shook him so much that he can’t even remember going to the test track later that morning. Several sources placed him there but, other than calling his mother, he has little memory of “The weirdest morning of my life.” Carmichael’s mechanic, Chad Watts, was getting dressed when he saw a second plane, United Flight 175 from Boston, plunge into the south tower of the World Trade Center at 9:03 a.m. EDT.

Honda’s Cliff White was already on Highway 14 with a 2002 CR250R and a cache of parts in a box van when he got a phone call. He was heading to the massive Honda Proving Center of California, a secluded and guarded 4000-acre facility in the Mojave Desert where the company could develop and shake down every single motorized product they manufactured. The bike was for Carmichael to ride. He left Kawasaki at the conclusion of the 2001 season. September 11-12 was his first official formal test with Honda and its Japanese engineers. “It was my wife,” White remembers. “We pulled over to the side of the road to listen to the radio. We just needed to stop.”

Suzuki’s Team Manager and Team USA leader, Roger De Coster, turned on the television, which isn’t normal for him. When interviewed for this story he couldn’t remember why he turned on the TV until his wife nudged him and said she was the one who told him to. It’s understandable that De Coster may have spent the entire day in a fog. At 9:37 a.m. Eastern, American Airlines flight 77 struck the south end of the Pentagon where his son Nigel worked in the State Department.

Roger couldn’t reach him. He didn’t hear his son’s voice until that afternoon.

Part 2: What They Did

When Kevin Windham arrived at the Suzuki test track later that morning, the bikes were unloaded and waiting for him. He struggled to bring himself there at all and remembers a strong inability to think clearly and make decisions. He wasn’t mad, wasn’t scared. Just lost and unfocused.

“There was no way I could have ridden a bike that day,” he says. He can’t remember what other riders were there, if any, but he knows that nobody started a motorcycle.

McCollum walked out of a box van and looked up into the crystal blue sky. He couldn’t believe it was true. No planes in the sky. Not a single jet stream. The airspace on the bluff where they tested usually looked like a busy intersection with streaks of white miles above earth crossing each other at right angles. Nearby, at Yamaha’s test track, Tim Ferry looked up at the same empty sky in disbelief. On the radio they both heard that all planes in the entire country were grounded. Seeing nothing but blue gave them chills.

“We were all dumbfounded,” McCollum says. “There’s this big tragedy going on and we’re going to ride a motocross bike? That didn’t make sense. We just sat there and listened to the radio.”

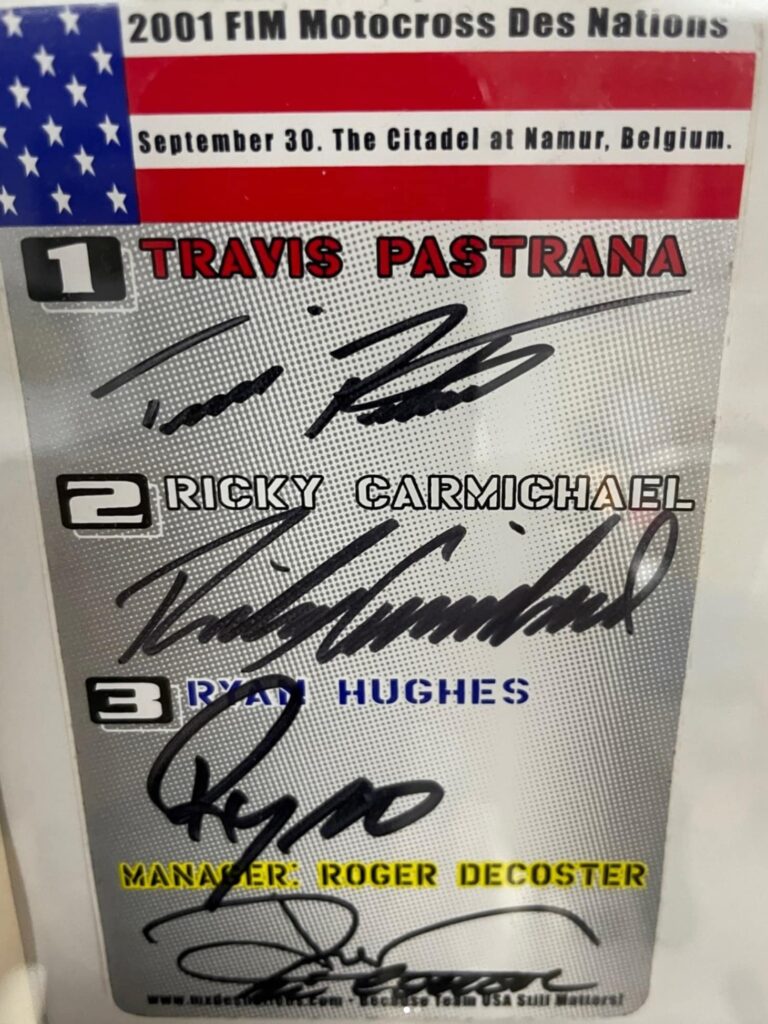

McCollum had helped Semar build up Windham’s RM250 for the Motocross of Nations. Normally, he spun wrenches for Travis Pastrana who was recuperating after a crash-filled summer cost them a repeat title in the 125cc AMA Pro Motocross championship. Pastrana was the original 125cc rider for Team USA but he dropped out of the AMA series on August 19. He suggested Mike Brown take his place.

Brown had plans to drive down to Cairo, Georgia to ride and train for the race. He can’t remember what he did for the rest of Sept. 11 but he knows he scrapped his trip south.

Carmichael and O’Mara drove the 175 miles from the beach to HPCC in Cantil, Calif. They listened to Howard Stern until the reception disappeared. Carmichael recalls a lot of chatter and a chaotic flow of information. The roads, however, seemed completely normal, lots of traffic.

“I don’t remember anyone reaching out to me or the other way around on the 11th,” he says. “I had a lot going on and I was on the moon basically. Little to no contact.”

They showed up to the facility and got straight to business. Ricky remembers working from 10-3 in what he calls a ‘learning day.’ They tested seat heights, handlebar bends, mounts, foot pegs… If those around him struggled to cope with the news coming from the east coast, he didn’t pick up on it. That’s textbook Carmichael. His strength as a competitor was eliminating distractions and staying focused.

That evening at dinner in a nearby town he remembers people chatting and acting less relaxed than normal. Later, inside his hotel room he turned on the TV and the weight of news hit him as he absorbed it with images that were replayed over and over. He watched footage of people leaping from the World Trade Center, the wreckage of Flight 93, a hole in the Pentagon. Piles of ash and rubble in New York City, entire companies of fire departments feared to be killed. “It was surreal,” he says. “Time seemed to stand still.”

Part 3: What Are We Going To Do?

This is where the memories get fuzzy. Like Semar, De Coster can’t place himself at the test track. He believes he went to the Suzuki race shop. But Ian Harrison, who ran R&D for the team, remembers Roger telling everyone to turn off radio at the test track in Corona. “That’s how he blocks everything,” Harrison says. “He just wants to put his head down and get to work.” Twenty years later, Harrison still works with De Coster, only now at KTM.

Windham showed up around 9:00 a.m. and had an ill feeling in his stomach. He had a flight booked to Belgium in two weeks and he couldn’t see that happening. He didn’t need time to think about it. America appeared to be under attack with commercial airplanes as weapons.

He already didn’t like flying. He took his first flight as a teenager to a race in Mammoth Mountain, Calif. and didn’t like it at all. The older he got, the more anxious he became. “September 11 cost me a lot of money,” he says. For the next seven years, he flew mostly on private planes. He said his travel budget ballooned to $1 million per year.

“I went straight to Roger and I said ‘I’m out’ [of the Motocross of Nations]. And I think it was that day [9/11],” Windham says. “I remember not really knowing how it was going to be perceived but also not caring. I had my own demons and issues to work out.” Mentally, he couldn’t put himself on a plane to Brussels. And that was before he knew that three of the terrorists who piloted the hijacked planes were radicalized in Hamburg, Germany, less than six hours up the autobahn from Namur.

Plus, he wanted to give De Coster as much time as possible to find and prepare a replacement. Windham didn’t recall that he was a replacement rider. The original open class selection, Ryan Hughes, suffered a severe concussion while practicing in late July. Then on Sept. 1, he broke his collarbone, ribs and partially collapsed a lung. It’s very likely, however, that Windham replaced Hughes earlier than Sept. 1.

“Wow,” Windham says with a laugh, when he’s reminded of the timeline. “It’s pretty bad when your back up rider backs out.” He doesn’t remember how long he was supposed to stay in California on this trip. He and Dottie rented a car and drove 1800 miles back to Centreville, MS. If any attempts were made to salvage a team and scramble to fill Windham’s spot, nobody can accurately recall. Yamaha’s Ferry, who finished third overall in the 2001 250cc AMA Pro Motocross season, can’t conjure a memory of getting a phone call, even though he wants to believe it happened.

On Sept. 12, Honda went back to HPCC and that’s when Carmichael first heard buzz about a possible withdrawal from the Motocross of Nations. White said he and Ricky talked about the situation and possibilities, just an open dialogue. No decisions. Carmichael needed more information, more time, and wanted to speak with his inner circle back in Florida. The news about Windham didn’t even raise his eyebrows.

“I knew how he was,” Carmichael says. “He was a worrisome person and it didn’t surprise me. I needed to know more about what was going on before I came to conclusions about what I wanted to do.” While Carmichael says he saw both sides of the argument (Stand up for your country on one hand. And, on the other, is a dirt bike race really important right now?) They couldn’t even fly home, let alone to Europe. Ultimately, he decided it wasn’t a good time to travel overseas. He said it had nothing to do with Kevin’s decision. Later that year, Carmichael told Cycle News, “My life is worth more than my pride. With what happened that terrible day in September, I wouldn’t want to go over there. I think that’s chancing it too much.”

Brown was pissed but powerless when he heard that his teammates backed out. He wanted to go. First, he spoke with Carmichael, then Mitch Payton. He wanted to put an exclamation point on what had been a fantastic season.

Payton also wanted to go. His father was a “tough as nails” Marine and he adopted the man’s ‘stand up and fight’ attitude. “But dad surprised me when he said we shouldn’t fly over there,” Payton says. “He reminded me that Brussels is the headquarters of NATO, which could be a target and we could wind up getting stuck.”

Preparing the motorcycles, spare parts cache and shipping crates required a lot of careful planning and going over checklists and customs forms. Jimmy Perry, Pro Circuit’s team manager continued that process while he waited for a decision. He said they were inserting the final screw into the lid of the crate when Mitch rolled into the shop and said “It’s official. We’re not going.”

The American Motorcyclist Association distributed the press release on Monday, Sept. 17. For the first time ever, Team USA would not show up to defend its title.

De Coster went to Belgium at the end of the month. So did Gosselaar, who was born nearby in the Netherlands and wanted to visit friends and family. De Coster admitted in an interview that he was a little worried while flying. In a pre-event festival in the city of Namur, he transferred the Peter Chamberlain Trophy to the FIM so it could be given to the winning team.

France won, and they did it with two replacement riders, David Vuillemin (250) and Yves Demaria (Open). Luigi Seguy raced a YZ125. In the post-race press conference, Vuillemin said, “I want all the people that doubted us to now stand up and say sorry. Yves and I have been given so much bad press.”

Windham and Carmichael eventually represented Team USA as teammates again. In France in 2005 they took back the Peter Chamberlain Trophy for the first time since 2000.

Mike Brown never raced at the Motocross of Nations. Now 49, he represented USA at the 2021 Vets MXdN at Farleigh Castle in Great Britain. Coincidentally, the dates of the race were Sept. 11-12. When asked if he’d still join Team USA for the official Motocross of Nations if asked, he didn’t hesitate to say yes.

And he’s not kidding.

Epilogue

The motorcycles were never ridden.

Pro Circuit removed Brown’s bike from the crate and reassembled it. It’s one of the many bikes in the showroom, which looks both like a museum and a dealership. Jim Bacon sort of wishes they’d left it in the crate with the sides open, you know, for posterity’s sake.

Depending on who you ask, Carmichael’s 2001 Honda CR250R didn’t get finished. Gosselaar said he built up the bike before Sept. 11 and it sat in the race shop. Chad Watts, who couldn’t have become a Honda employee until at least September 3 (he was Carmichael’s Kawasaki mechanic through the Sept. 2 finale) said the bike was in pieces. He said Gosselaar had built up the chassis but the rest of the parts were still waiting for assembly. When the team withdrew he says he personally cut up the frame and recycled it.

Either way, the bike doesn’t exist anymore. An employee who worked with Honda in 2001 and still works there today said the bike is not within its museum inventory and added, “It has no relevance. We didn’t save a bike unless it was a championship winner.”

Alley Semar wanted Windham’s Suzuki and he grew frustrated watching it sit untouched at the race shop until the day he left the brand in late 2002. Today the bike sits in a private collection in East Moline, Illinois. Anyone interested in purchasing it should contact Rick Doughty at Vintage Iron.

Simon Cudby shot the studio photos posted here just before September 11, 2001. He took them at the request of Racer X Illustrated and said the bikes arrived one at a time, which is why he didn’t shoot all three together. He used 120 medium format film for the tight shots and 4×5 large format film for the profile versions. Popular with professional landscape photographers, 4×5 images show incredible amounts detail. Like Carmichael’s physical bike, the profile images of the CR250R went missing. They could be misplaced among stacks of binders and slides.

A second photo shoot with the unridden machines happened with Kinney Jones after September 11. Watts met Payton and Semar at Pro Circuit and loaded up all three bikes into the back of his pickup. Payton snapped photos of the three different brands jammed into the bed of the truck. Watts said excited and gawking motorists who recognized the significance of his cargo almost ran into him on the highway as he tried to drive to Riverside. Jones vividly remembers taking photos of all three motorcycles together. Nobody knows where those photos went or who used them, including Jones.

At some point that month or that fall, at the Pro Circuit race shop, a group of friends and employees stood around drinking beers and bench racing. Someone got out a piece of cardboard and a marker and wrote “FUCK YOU BIN LADEN” on it. They posed for a picture behind Brown and Windham’s Team USA bikes, their sign and middle fingers raised toward the lens.

Where were you on 9/11? Join the conversation on our social posts about this story.

And if you value these stories and want to keep them coming, buy products straight from shop.wewentfast.com