“Miracle”: An Austin Forkner Story

By

Julie spent years trying to get pregnant; her chances were low and she gave up. Then Austin came along.

Julie Forkner prefers to spectate alone. But first, a simple ritual: before her son, Austin, climbs on his motorcycle, she gives him a hug and tells him ‘you got this.’ She leaves the race truck after Austin. Every time.

Then she separates from her husband, finds an empty stretch of fence line and morphs into an unrecognizable mental and emotional state. It almost seems like an act; her mood changes abruptly, she gets very quiet and takes deep animated breaths. Her hands press together, the tips of her fingers rest at the base of her lips and she walks frenetically back and forth like a cartoon detective trying to solve a case.

When the motorcycles fire and the 30-second card floats above outstretched arms her pacing lengthens. She fidgets and shrieks. Comfort is not important here.

Today’s spot is against a chain link fence on the outer property edge of Budds Creek Motocross Park in southern Maryland. Between us and the racetrack is a worn strip of grass, a 25-ft. wide paved lane, a thin line of spectators, another chain link fence and thigh high banners that follow the path of the course.

It’s 1:00 p.m. in mid-August and we’re unprotected from the sun. We’re also standing in front of a temporary speaker wall brought in just for this event: the 11th round of the 2018 Lucas Oil Pro Motocross Championships. We’re sandwiched between the dueling noises of 40 four stroke motorcycles and the announcers desperately trying to be heard over the drone.

My skin and ears ache but if any of it bothers Julie she doesn’t let on. She’s a thin and rugged woman who has worked hard her entire life. She rolls her t-shirt sleeves to her shoulders to reveal long, deeply tanned arms. Her denim shorts are cuffed just above the knee, she wears eyeglasses, a slim watch on her left wrist, black Nikes with white soles and no hat, despite the oppressive sun. Her golden brown hair is tied in a messy bun. Strands fly forward and she unconsciously tucks them behind her ears.

The gate drops. The race starts and the next 36 minutes will be an emotional seesaw, one where the person on the other side keeps jumping off. It seems ironic because she knows how to deal with stress; she has 35 years of elementary school teaching experience. But that stress is different. None of those children are hers.

People walking by stare at this odd sight, a middle-aged woman pacing frantically, gesticulating, talking to herself, clapping loudly. Take this scene out of context and place her on the streets of Pleasantville, USA and someone is calling the cops. She runs back and forth across the road to cheer on just one rider before returning to her area of isolation. She walks a mile or two during the race but goes nowhere.

If worrying can equate to a form of protection then her son is in a bubble. He might be an adult, might have other women in his life and might make more money (on February 9, 2019 he made as much money on that night than the average Missouri school teacher makes in a year). But he’s still her little boy and she wants to protect him. It’s for him that she suffered, bled and questioned her own faith.

That Austin Forkner is alive at all is a miracle.

Forkner is a refreshingly funny and quirky kid. He wears bright yellow Sponge Bob socks and the type of white cat eye sunglasses Audrey Hepburn once made fashionable. He rides push scooters, can backflip a BMX bike, plays video games and isn’t afraid to admit he drinks Dr. Pepper soda more often than he probably should; every other day he allows himself one.

“That’s probably the biggest thing that I want to eat or drink, but I try to hold myself back,” he said. He loves it so much he bought a hoodie with a giant Dr. Pepper logo on it. He’s also a creature of habit. As a child he ate SpaghettiOs for lunch for six straight years. He doesn’t hesitate to say he still eats them occasionally.

Forkner has a shy side that most people don’t see. It’s not evident in the videos he posts to his YouTube channel, or in the interviews he gives on television, or in recorded interviews. That’s because his mom practiced with him as a young child. He’d race up to her on his bicycle and she’d engage him in an impromptu victory speech. That all came easy, but he didn’t let his parents out of his sight.

He refused babysitters as late as three years old and his parents once had to bait him with monster trucks to trick him into staying at grandma’s house for a day. He couldn’t be fooled twice. On the first day of kindergarten, after Julie dropped him off, he cried so hard he vomited.

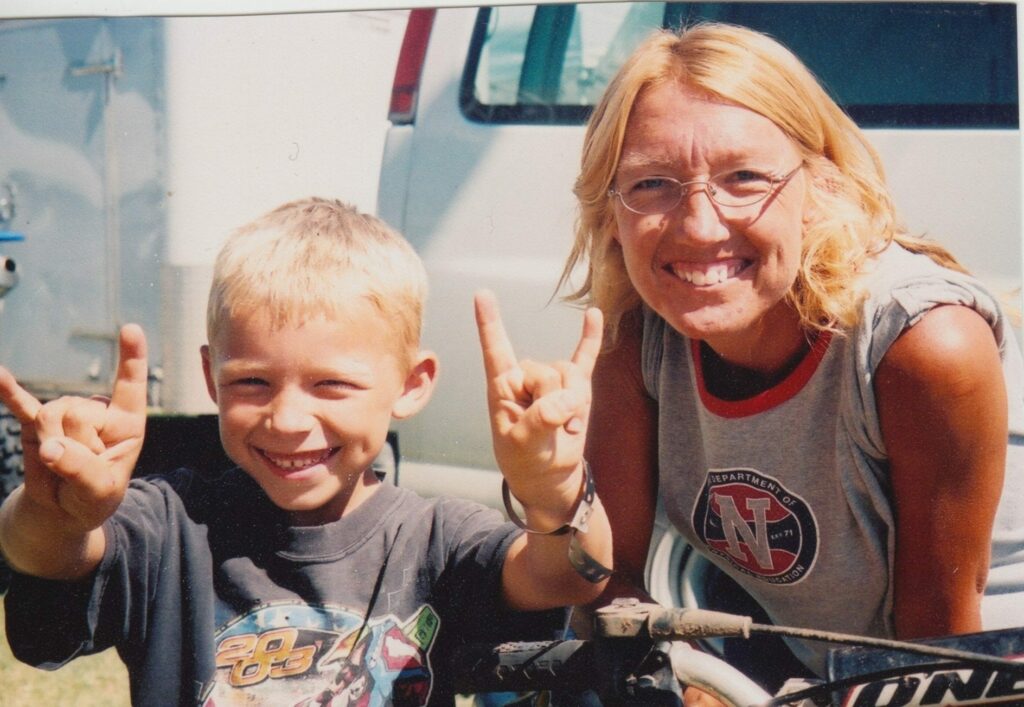

“I was kind of a mama’s boy when I was younger,” he unabashedly says today.

Now 20, Forkner rents a house in central Oklahoma and he enjoys living on his own, splitting cooking duties with his roommate. His father, Mike, sleeps 15 minutes away in a cabin at Robbie Reynard’s training facility where Austin practices and trains. Austin hired his dad to be his practice mechanic. Even though Mike is always present at the track, Julie calls every day to check in. And it’s Julie whom Austin calls when he stumbles.

In November he crashed and knocked a few ribs out of place and strained his neck and back. He called mom, who remains based at his childhood home in Richards, Missouri, four hours to the northeast. She could tell he needed her.

“Mooom,” he said over the phone, elongating the word. He had that hesitation in his response when she asked if he was ok. “You never know how these accidents are going to turn out so I always want him to call me and tell me,” she said. “He’s never shy about it. I feel like when he calls me it’s a sign that I need to go see him.”

The sport didn’t create Julie’s nervousness. This is deeper than dirt bikes.

The Miracle Worker

Dr. Judy Parton saved Julie’s life first. Later, she saved Austin’s. As a young adult Julie battled endometriosis. Around 1989, she came home from work one day doubled over in pain. She laid down on the couch, “and I never lay down or sit around.”

In the early evening a friend rushed her to the emergency room. After three pints of AB Negative (the rarest human blood type) the internal bleeding slowed and her levels improved. She walked up and down the hallways and thought ‘I’m ok.’ Statistically, she seemed ready for discharge but the emergency room doctors still didn’t have a reason for the cause of her visit.

Dr. Parton’s office was next door to the hospital and she made rounds after seeing her patients for the day. When she saw Julie’s name on the charts she popped in to say hello and ask questions. Dr. Parton was Julie’s primary care physician and knew her history well.

She had a hunch and wanted to examine further. Using an arthroscope, she discovered a ruptured ovary. After surgery, Parton told Julie she would have been dead within 12 hours had she been sent home. That was the good news. The bad news? Her chances of having another child stood at 10%.

I was kind of a mama’s boy.

–Austin Forkner

She didn’t mind the reproductive challenge, even with skewed odds. A barrel racer from Nevada, (nuh-VAY-da) Missouri, she grew up a competitive child who hated to lose.

If she missed a free throw in a basketball game, the next day she punished herself with an extra hour of shooting after practice to ensure it wouldn’t happen again. Julie and Mike might both be former racers but she’s the cutthroat one. She wanted a second child. Mike wanted a first. In 1984, at 22, Julie had a daughter named Mandy from a previous marriage. She married Mike in 1990.

The shots of Clomid cost $880 a month and insurance didn’t cover them. A quarter century later, Julie still has the receipts in her house. One year on, six months off, one year on, she and Mike spent tens of thousands of dollars before finally conceiving a child.

In the spring of 1996 they started telling family and friends just before they went in for the first sonogram at five or six months. If the baby was a boy they had picked out the name Matthew to keep an alliterative roll with their daughter: Mandy and Matthew.

In the ultrasound room, the silence was painful. Someone suggested they go get Mike, who stayed in the waiting room. When the doctor joined and examined with the technician, Julie didn’t need anybody to say anything. She could tell just by looking at the doctor’s face.

He relayed to the Forkners what he saw: missing pieces of his brain, missing heart valves, didn’t have a stomach… the words became a drone and eventually she heard nothing. They were sent to Springfield, Missouri, to a hospital with more specialized equipment. Julie cried the entire way.

“Everything went downhill,” Julie said. “I thought, ‘this is a dream and I’m going to wake up in a minute.’ Then you realize it’s real and you start making excuses in your head.” In Springfield they discovered their unborn child had Trisomy 13, a chromosomal condition that affects one in 16,000 newborns. It’s associated with severe intellectual disabilities and physical abnormalities.

Everything went downhill. I thought, ‘this is a dream and I’m going to wake up in a minute.’

–Julie Forkner

Julie didn’t bother to fully research Trisomy 13. It didn’t matter. Nothing could be done. She can’t remember if Matthew even took a breath when he was born. Despite having more than two months to steel herself, Julie was distraught. The process of getting pregnant tested her faith. Giving birth to a child she’ll never know caused her to question it.

“You think that, because you try to be the right kind of person and you do the right things, that God owes you something,” she said. “I thought, ‘I’m a good person, I take care of kids for a living. I want my own family.’ But God doesn’t owe anybody anything.”

Matthew is buried at the cemetery a quarter mile from their house. A headstone dated August 8, 1996 has an angel carved in it with the words “Infant son of Mike and Julie Forkner.” She walks by it almost every day. Emotionally, physically, financially, she had nothing left. “I was done.” And her heart ached for Mike who wanted a son. She returned to her teaching job the next week but the emotional recovery lasted for months. She was extra sensitive to the lives of other kids. “I saw so many parents who had kids they didn’t care about and all I wanted was one more.”

The physical pain from the endometriosis didn’t go away either and during Christmas break 1997–after 14 more months of trying to get pregnant–she visited Dr. Parton to schedule a hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus. Dr. Parton, however, had another hunch. She saw something. The blood test came back negative but Julie remembers the doctor saying “I just have a feeling. I think you’re pregnant.”

No way.

Julie was 36 years old. She had given up, not because of her age but because of what she had been through. “The possibility of having another kid did not occur to me.” She’d had no symptoms. She thought the doctor was just stalling. During the second week of January 1998, Julie reported a stubborn flu. The doctor told her to buy a pregnancy test. It registered positive. When Julie informed Dr. Parton, she said “Holy cow, I was right!”

Julie turned to Mike and asked “What do we do?” They had as much apprehension as excitement and they didn’t share the news with anyone, not their parents or even their 13-year-old daughter. Julie didn’t gain much weight and she wore clothes with extra room.

In the spring they did amniocentesis to test for genetic abnormalities and birth defects. After waiting 10 agonizing days for the complete results she got the news that she was carrying a perfectly healthy baby. On September 2, 1998, the same day his sister Mandy was born in 1984 (and–wild coincidence–the same day Mandy’s future husband was born) Julie gave birth to a baby boy. They named him Austin, Julie’s maiden name. The Austin bloodline ends with Julie’s father, Larry, but now lives on in the first name of her second born son.

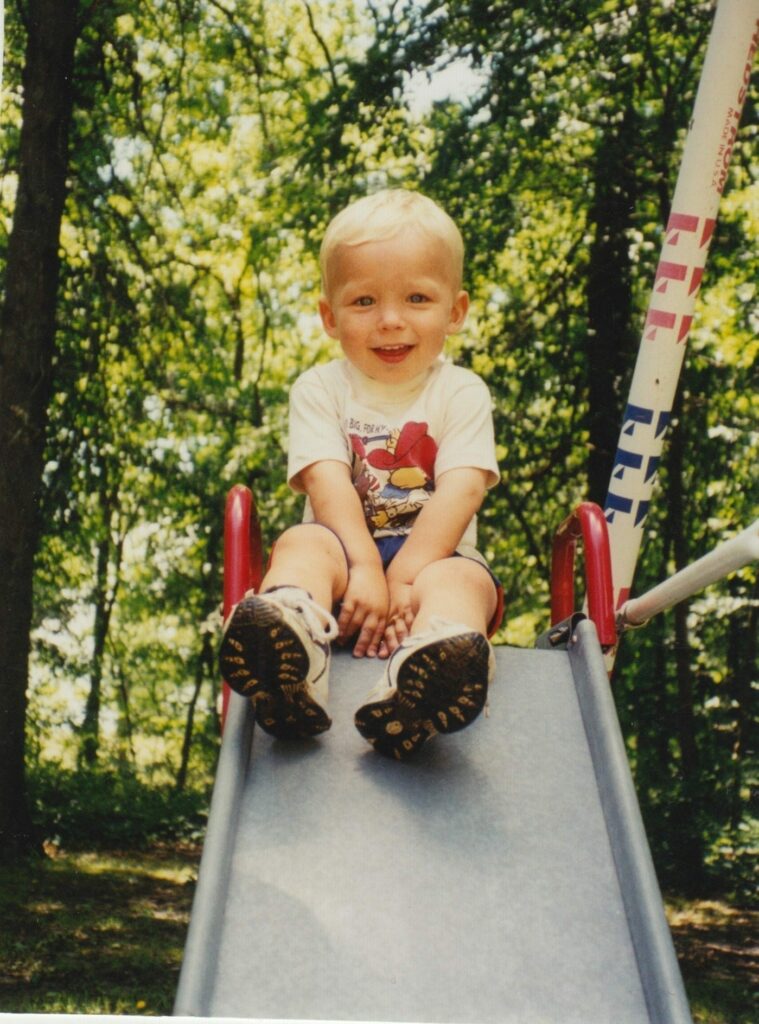

“How crazy is it that he would make it?” Julie said. “We never dreamed he would be the one.” Julie had already raised one kid from infancy to teen and she remembered how quickly they grew and how fast the phases changed. She carried him everywhere, rarely setting him on the ground. As he grew, he saddled up on mom’s hips while she worked around the house and Julie soaked up every minute of it. People warned her that he wasn’t going to learn to walk if she didn’t put him down. “I never wanted to let him go. When you go through all that, you want to protect him forever. I just still see him as a little kid. He goes fast on a big bike but he’s just my little boy.”

Life on the Farm

Farming came first in the Forkner house. Then motorcycles. With 4000 hogs, 100 cattle and 1200 acres to tend, the only time left for motocross came on Sundays. Mike Forkner spent 30 years as a crop farmer before his son became a professional racer. The corn and soybeans went into the ground in April. Wheat was harvested in June. In September and October, the spring crops came out of the ground. July and August, the prime growing months, meant motocross.

“The whole racing season revolved around the farm schedule,” Mike said. One year the wheat came out a bit early and they used the bonus week to go race at Mammoth Mountain. In the chillier months they hit the amateur majors when they could. They used creative ways to afford the biggest amateur events. The Forkners knew their son was good but they weren’t going to mortgage the farm to pay for racing.

Austin remembers going to the racetrack before he ever got on a bike. Mike started racing at 29 years old, following his brother Stephen. Bikes could always be found leaning against the walls of the family barns. Austin couldn’t turn well when he first rode his PW50. He traveled in a straight line between two adults, either mom and dad or grandma and grandpa. He once fell over on the throttle side and caught his arm on the spinning rear wheel. The memory and the visual of the painful rub marks kept him off the bike for a couple of months.

Motocross got squeezed in alongside basketball, bicycles and showing pigs at local fairs. He once won a blue ribbon. Racing wasn’t a full pursuit. Forkner stayed farm bred and corn fed, a normal kid.

He went to public school through seventh grade and, when he needed money to buy new video games or a bicycle, he shoveled manure out of the 100-ft. long pig troughs. He got $5 per barn. Each barn had ten pig pens and Grandma Ruby kept a close eye on the quality of the work at payment time.

That work ethic is noticed by those he works with today, such as his race mechanic, Olly Stone, with whom Austin has stayed when testing in Southern California. An early riser, Stone woke up one morning to find Forkner already cooking breakfast and heading out the door to train.

“He’s easy to work with,” said Robbie Reynard, Forkner’s riding coach. “You tell him to do something, he does it. He has the work ethic. That’s hard to come by. That’s a good quality to have.”

To chase amateur motocross titles on a budget the Forkners worked with what they had. That meant a simple, white 6×12-ft. cargo trailer and a Dodge Ram that doubled as a work truck on the farm. The three of them slept on an air mattress in the back.

At the Winter Olympics (Mini Os) they huddled together to keep from freezing. At the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championships at Loretta Lynn’s they sweltered. In 2006, their first year competing at Loretta’s, Mike left the doors of the trailer open and used a small, battery-powered fan to circulate the thick air. On the first morning, Austin, allergic to mosquito bites, woke up with a severely swollen face.

“It looked like he had horns on his head,” Mike said, laughing. They rushed off to a clinic inside a nearby Walgreens for treatment.

In 2010, the Forkners showed up to Loretta’s for the fifth straight year, still driving a Dodge work truck, still pulling the 6×12-ft. trailer. A local dealership offered Austin a little support and he got two sets of free gear from MSR. With just one Suzuki RM85, Austin competed in the 85 (9-11) Stock and Modified divisions and won both classes, his first two of six titles at Loretta’s.

Julie remembers people seeking them out, the kid from Missouri who won the opening modified moto on a stock Suzuki. They had a hard time believing the simple setup.

He came in to Tennessee that year with a best finish of 12th in five tries and left with two titles and a sponsorship from Fox Racing. Team Green came shortly after but everyone resumed their normal lives. Austin went back to public school and scraping troughs for pocket money. Julie returned to the classroom; Mike went back to farming. They raced or rode only on weekends.

“I never wished I could ride more,” Austin said. “There wasn’t a point where I needed to.”

The Prospect

Raised in an era where access to tracks and competition became paramount for success, the Forkners avoided training facilities. They wanted their son to be a normal kid. “I think that’s why I still like to ride. I didn’t get burned out,” Austin said in a 2016 film titled “Fox Presents”. Besides, work had to get done on the farm. A popular quip in the Forkner house goes, “Sometime you do what you gotta do, not what you want to do.”

Forkner had options for 2016, the year he declared professional status. GEICO Honda offered more money than Pro Circuit Kawasaki but it didn’t make the decision any easier. In the summer of 2015, Mike and Austin took a trip to California to meet with Mitch Payton and test the race bike. Although he had been a Team Green rider since 2011, Austin wasn’t a Pro Circuit rider.

Jim “Bones” Bacon, who recently retired after 34 years with Pro Circuit, said Forkner didn’t get suspension and engine support and, from his point of view, he didn’t see Austin headed their way. A test at Milestone MX Park ended up as much an ice breaker as a riding session. Payton invited the Forkners to his house and put them up in a loft apartment on the property. The hospitality, and the way Austin hit it off with Payton’s twin sons, helped close the deal.

Bones enjoyed having the Forkners around for his final years on the team. “He’s a quiet, stick-to-himself kid,” he said. “He sits and he’s focused. He’s not in the lounge and watching TV. We don’t have to tell him to get off social media or stay off the phone. We’ve had riders where we’ve had to take their cell phones away. We’ve had to ban girlfriends from being in the lounge. That kid wants to win and he’s willing to do whatever it takes. He’s not a big bragger and he is still a kid at heart, still rides his scooters around.”

In late January 2016, 17-year-old Forkner debuted in the Amsoil Arenacross series in Allentown, Pennsylvania. He had a bumpy night: eighth in seeding and needed the Last Chance Qualifier to make the main events where he finished fifth and fourth, respectively. Eight days later in Greensboro, North Carolina he won his heats and both main events. He delayed his supercross debut until 2017 but finished 4th overall in Lucas Oil Pro Motocross with five podium finishes.

Austin’s gift of speed and style are still gelling with a racer’s requirement to exercise poise and patience. After two and a half years, his longest podium streak happened in his rookie season in the final four rounds of motocross (2-3-3-1). In his sophomore supercross season he earned his first two 250SX career wins back to back (Tampa/Atlanta) and then finished third at Daytona.

Then, in Minneapolis, after two rough weekends, he had a (very) forgettable night. During the second race of the Triple Crown formatted event, he fell four times. In the third main event he went over the bars and separated his shoulder, ending his supercross season. Lesson learned.

“I just didn’t want to get beat,” he said. “I didn’t want to accept not on a podium spot or not first. You just have to accept not winning and getting second and just take it. People are going to be like, “What happened? You weren’t riding good.” But you can’t worry about what other people have to say. If I would have just maybe accepted getting a third, fourth, fifth that night, then I may not have been out for the rest of the season.”

Some parents can’t watch their sons or daughters race at all. Julie Forkner, however, is caught in an internal horror story; she can’t watch and she can’t not watch. She’s never missed a major race, amateur or professional. With her remote midwestern location, she has employed extreme measures–slept in airports, hitched rides–to make it to her son’s events.

“I’ve watched with Sonja Stewart (Malcolm’s mother) and she just sits there,” Julie said with disbelief. “When my boy is on the track it makes my stomach almost sick.” In July 2017 she hit a low point where she’d had enough and didn’t want to be around it anymore. Austin crashed hard training in Oklahoma; he hit his head and lay motionless on the track for several minutes. When he regained consciousness, he rolled around on the ground in a panic; he was blind. Mike called Julie. “Austin wrecked, it’s really bad,” she remembers him saying. “You need to come now.”

In the hospital Forkner fought with his caretakers and mixed gibberish in with his words. Austin asked for water and then swatted it out of the hand of the person who tried to give it to him. He asked to use the restroom but then urinated next to the toilet instead of in it.

Then he made one coherent statement nobody mistook: “I love you, mom.” Julie hadn’t arrived, though. He’d heard the voice of Robbie Reynard’s wife, Ashley. When Julie arrived in Oklahoma City, she found Austin sedated because of the uncontrollable anger. She had driven four hours to see and speak with her son only to find she still couldn’t communicate with him. She cried the moment she saw him.

Austin’s crash resulted in a severe concussion. The blow happened specifically above the eyes. He woke up calm and asked what had happened. Then he gave himself a body check. He doesn’t remember anything about the crash and only knows what he was told: caught a foot peg, hit his head. Austin asked when he’d be able to ride again. He received sympathetic stares in return.

“I didn’t really realize how bad off I was right then.” When handed a cup of water, he didn’t know what to do with it. When handed a sheet of paper and a pencil, he had delayed visual processing. After concentrating, he saw a connect the dots exercise.

“I knew I wanted to connect this dot to that dot, and just draw a straight line, but I couldn’t really do it,” he said. “I could see my hand and I would be like, ‘all right, just do it.” That was whenever I was like, ‘I’m actually pretty messed up from this.’”

He spent three weeks away from his phone and video games and nearly two months off the bike. He eased himself back into riding on a sandy turn track. Two months later he broke his left wrist and collarbone and spent another eight weeks off the bike, putting him behind in preparations for the 2018 racing season.

On April 14, the night Austin crashed out of the supercross championship in Minneapolis, Julie paced back and forth across the floor of a babysitting suite in U.S. Bank Stadium. Still holding Tyler and Bradi Bowers’ baby daughter in her arms, she headed to the Alpinestars Mobile Medical Unit.

Ten months later, in the same stadium, Forkner dominated the 250SX East opener. Julie battled an ice storm to be there, to watch with the nervous energy she’s by now well known for.

“You Got This.”

The crowd leaning on the fence at Budds Creek eventually figures out who she is, this woman who only walks up to clap and yell when Austin Forkner rides by. They start cheering wildly for him, too. She once tried to spectate among the people, even sit in the bleachers, but sitting made her antsy and people around her wanted to chat and ask questions. She didn’t mind being social but she couldn’t focus her energy on Austin. So she isolates herself.

The announcer yells “rider down!” and she involuntarily shrieks and elbows me in the ribs. There’s a one in 40 chance it’s her son but until she sees him ride by she can’t breathe. “Come on, come on, come on,” she repeats, like she’s willing the clock to spin faster. She grimaces, squeezes her hands into the side of her head, bites her nails, pinches her lips and stretches her arms toward the ground, balls up her fists and walks frantically with her head down. When Austin crosses the finish line, Julie snaps out of the hypnotic trance that took over her body.

At the race truck she doesn’t act like the same person who, moments ago, wanted to wrap her son in layers of packing bubbles. She picks up his dirty riding clothes, asks him questions about the race and gets him food and fluids. Austin sits in a lawn chair wearing only socks and underwear.

A pile of riding clothes surrounds him while he gnaws at the callouses on his hands and blankly stares beyond everything happening in front of him. His usual unkempt and bleached hair is gone, replaced by a fuzzy shave job. He lost a bet to Reynard.

His deep blue eyes are lost in a persistent squint. If he says anything, nobody hears it. He’s not feeling well today. Two days ago he had a fever. He’s still lethargic. He pulls off his socks and sinks into a 30-gallon wastebasket full of ice and water. It doesn’t faze him and his stare deepens.

After the soak, he wraps his lower body in a lime green towel and grabs two rolls of Smarties candies and a small handful of pills left for him in a paper bowl. Wearing the towel, he watches 450 moto one on a TV hanging from the exterior side of the Pro Circuit Kawasaki truck. He doesn’t get lost in his smartphone or other modern distractions. He doesn’t even allow himself the enjoyment of air conditioning.

After an hour, it’s time to do it again. He pulls on dark headphones that blare AC/DC or Metallica or Green Day, or any one of the classic rock acts that filled stadiums before his time. The musical tastes came from traveling to races with his dad and loading the discs into the Dodge Ram’s CD player. He doesn’t understand today’s music. “The newer stuff just kind of sucks,” he said. Gearing up, his jersey gets caught on his body protector. Julie fixes the snag but he doesn’t seem to notice. He’s staring again. She hugs him, gives him a fist bump and tells him “You got this.”

The son she carried everywhere as a child rides away on a motorcycle and Julie returns to her spot along the fence, alone.