Little Giant: The PW50 Story

By

This is my earliest memory. It’s December 1982 and I’m three years old. We walk up an exterior set of stairs to a second floor corner unit of a mid-Michigan apartment building. A man opens the door, greets me and my father and invites us in.

Inside the living area, toys are piled up against a wall. But no one else is in the apartment. Outside a sliding glass door, I see a playground. I’ve been told I took more interest in the toys than the motorcycle that brought us there.

I can still see the man starting the bike. He grabs the tiny black grips and contorts his spine into an arc to position himself to depress the kick starter. After several swipes of the lever, the bike idles with a hollow ‘chug, chug, chug’. He rolls open the throttle and blue smoke spews from the exhaust. The bike has sat for a while. It sounds like a throaty weed whacker.

These images have been consistent in my memory for nearly 40 years. Today, I wonder why the man sold it. He seemed to have a child still young enough to ride the gently used bike. The fenders still had warning/safety stickers and the number plates had the black/white Yamaha #1s.

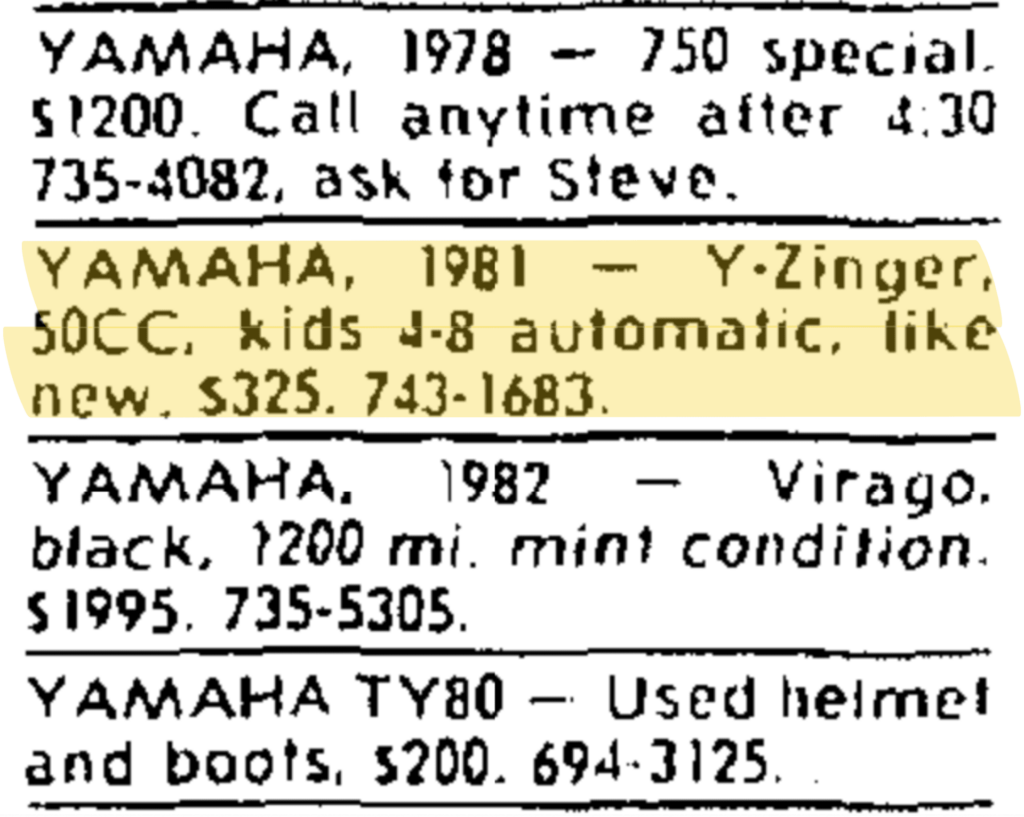

Maybe the parents got divorced. Maybe the kid didn’t like the bike. No matter; one man’s desire or need to sell was another man’s impulse buy. A few days earlier, my dad and a co-worker pored over The Flint Journal classified ads and discussed touring motorcycles. The man pointed out an ad for a Yamaha YZinger and said, Here’s a bike for your little boy.

“I didn’t know what a YZinger was,” dad says today. “But I was all excited. I was a young dad with a little boy I wanted to get into motorcycling.”

That’s the story of how I got a 1981 Yamaha YZinger, the first model year of the iconic bike now known as the PW50. In the forty years since the YZinger PW50H showed up at the September 1980 dealer meeting in Las Vegas, over 380,000 have sold worldwide in 150 countries. But the true number of kids who can call the PW50 their first bike is incalculable because these little bikes never stopped running. And when the original owner outgrew one, they went to little siblings, got saved for unborn children or sold quickly and easily to someone ready for the thrill of riding.

Josh Voth, the sales manager for Chaparral Motorsports in San Bernardino, Calif. said he’s never seen a PW50 roll back into the shop for trade-in. Ditto for Nico Montoya. He works at the oldest Yamaha dealership in the United States (1956): Bobby J’s Yamaha in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He said the only PW50s that come in their doors are for service and that’s only when someone finds a long neglected one in a barn and can’t get it running on their own. “We know those things like the back of our hand,” he says. “We can get them running again easily and cheaply because parts are easy to find.”

That’s because the bike barely changed over four decades. When they do run again, they cough up a thick blue haze and early memories for wide-eyed youngsters.

“Toy-Like”

In the fall of 1979 Yamaha delivered the YZ50G, the brand’s smallest closed-course competition model. The 9-horsepower, 5-speed screamer produced 4.5 pound-feet of torque at 10,000 rpm. Damon Bradshaw rode one before he jumped to the Junior Cycle class.

The moment the YZ50 hit the market, however, Yamaha killed it. Product planners and engineers started pre-production on what they called the “Little Giant”. Yamaha saw an opportunity in the market and a hurdle that needed lowering. They saw bike sales slowing in the late 1970s and wanted a bike that riders could have fun with, didn’t worry parents and also didn’t intimidate with costly and complicated maintenance. One popular keyword from the initial meetings was ‘toy-like’. But they also wanted it to look like a real dirt bike.

“The target was complete beginners, kids around five or six years old, kids that had finally learned how to ride a bicycle could now experience the fun of controlling their first motorized vehicle; that was the visual we were after,” says Takashi Matsui, a retired Yamaha engineer. The image they had? Christmas present; something small enough to fit down the chimney.

Designers drew several full-scale sketches to repeatedly review and discuss the design until everyone on the team shared the same vision. A silhouette with a rounded, cartoonish look emerged. The three-part set of the fuel tank and front and rear fenders had one-piece construction using flexible plastic. The seat extended over the fuel tank in a unique shape, as the designers envisioned kids using both legs to walk the bike forward while seated.

“The engineers would begin to massage and rework relative to what the input was. That whole process we’d go through several times,” says Ed Burke, another Yamaha retiree who worked in product planning and development. “Sometimes it came out as expected. Sometimes there were problems. That whole process we’d go through several times.”

In his nearly 40 years with the company Burke flew to Japan 350 times. Some models required a half dozen trips or more. The YZinger, however, required only three trips across the Pacific because development happened in months rather than years. The PW borrowed from two existing – and well tested – Yamaha products.

Matsui’s team used key components from two scooters already in production – the 10-inch wheels from Yamaha’s Passol and the powerplant of the QT50, which had a 49cc single cylinder automatic transmission engine with a shaft final drive. “Having that power information is key because engines are the largest part of development,” Burke says. “And the most expensive.”

Designing bodywork to tie together the wheels and engine gave the development team its biggest hurdle. They wanted to use as few parts as possible to keep the price low.

The QT50 scooter, also known as the Carrot and Yamahopper, hauled teenagers and adults around city streets; it proved durable. The motor had a tame 2.8-pound-feet of torque at 4,500 rpm but Yamaha wanted parents to have more flexibility. So, Matsui did something that went against everything else he’d done in his career: make a motor slower. Matsui worked on the fabled YZR500 road racer. He didn’t have much experience slowing bikes down. He added two power limiters: a speed adjustment screw in the throttle and a power reduction plate in the exhaust pipe, which could be removed.

“At first, we put a plate with a 7 to 8 mm hole in it in the exhaust pipe, but that reduced it too much so the rpm wouldn’t come up and the bike wouldn’t move forward,” Mastui says. “There wasn’t enough rpm to engage the centrifugal clutch. In the end we altered the size of the hole in the plate a number of times and eventually fixed it. Thinking back on it, it’s a pretty funny story.”

Yamaha gave parents two gifts in the design of the PW; they could adjust the bike’s power and they needed very little mechanical knowledge to maintain it. Shaft drives are durable and chainless and the two-cycle engine came with an oil injector. This meant no ratio calculations to mix gas. With a seat height of only 19.1-inches, little feet could touch the ground easily. At only 80-lbs. dry, children could paddle around on it and parents could lift it into the trunk.

Following the September 1980 national dealer meeting, the PW went to the major motorcycle shows in Europe (where the bike was called the “Mini Mini”. Cycle News didn’t mention the bike at all in their coverage. The issue following the Las Vegas meeting featured a 750 Virago on the cover with the headline “V-Twins in Vegas”. The only dirt bike mentioned in the issue was the YZ125, which got revolutionary water cooling.

Dealers took notice, however. At $439, Yamaha planned to sell 8,000 in 1980. Instead they sold 17,000. In 1981 that figure nearly doubled to 33,000.

The rush to get them under Christmas trees was on. Newspapers in all markets featured small ads with clever tag lines: “A Mini-Mini with Many, Many Advantages” (Berskhire-Eagle; Pittsfield, Mass.); “How to make your kid light up this Christmas” (The Daily Tribune; Wisconsin Rapids, Wisc.).

For the industry publications, Yamaha purchased full spreads and produced a campaign titled “Training Wheels”. A profile photo of the YZinger on its center stand, with the tail end of a full-sized YZ next to it – sat beneath five columns of ad copy with this lead sentence: “If you’ve been searching for the perfect beginner’s dirt bike for your beginner, begin here.”

Before the YZinger

The PW50 was not the first tame 50cc motorcycle aimed at new riders. Honda had the QA50 and Z50A, Indian had the Mini Mini and Suzuki released the JR50 in 1978, a little brother to the RM50. Even the Sears catalog offered a 4-HP 4-cycle tractor motor bolted into a boxy, tubed frame (only $189.95 for Christmas 1969!).

The PW, however, changed the game. Its power adjustability could go from tame to torrent. To a kid it looked both fun and ferocious. It made developing the habit of riding easier. Even going racing was a breeze. Heck, it came with numbers on the number plates. The PW50 shook up the pee wee scene, which (depending on where you lived) suffered from a lack of organization and participation. In the late 1970s and very early 80s, the 50cc class – known as the mini 50, pee wee or mini diggers, depending on the region – had little structure. Lots of manufacturers produced bikes but they were far from equal. Motorcycles ranged from the aforementioned tractor motors in frames to “Indians” exported from Italy by Italjet (that’s a whole other story).

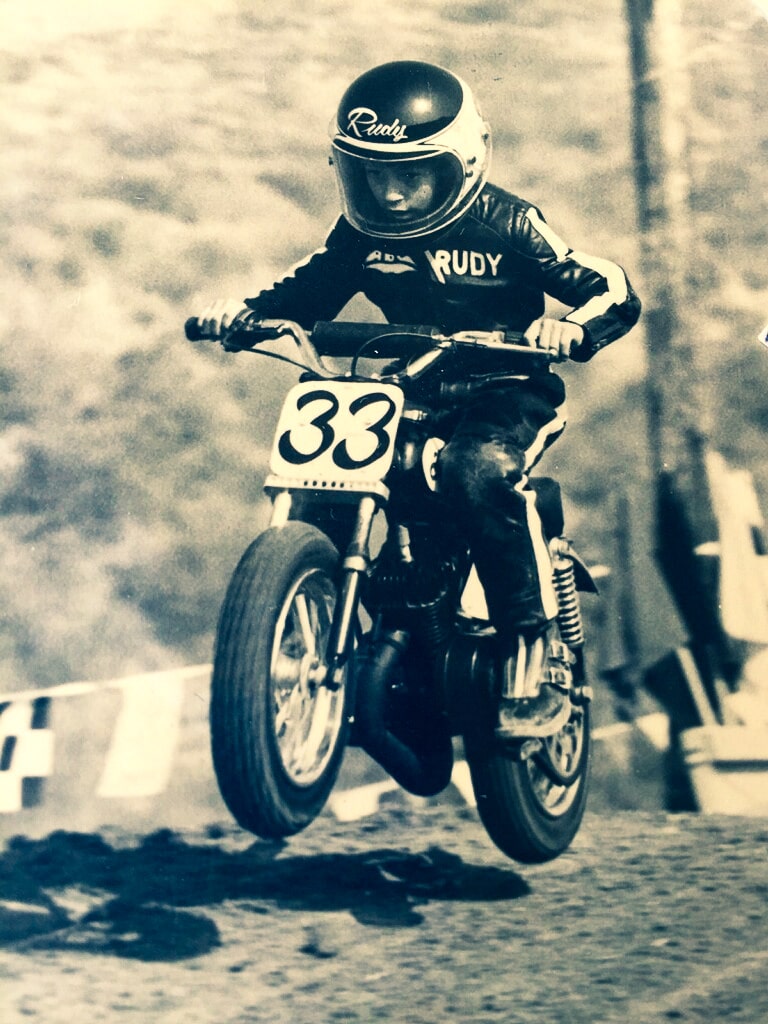

Glen Dickinson had one of those Indians. His father, Rudy, took an already competitive motorcycle and fabricated an expansion chamber exhaust, a lighter and stronger frame, better suspension and made a billet crankshaft and hubs, among other modifications. They ended with a miniature motorcycle that could hit 70 miles per hour, “and still burn the rubber off the tire, Dickinson says. “If your dad wasn’t hop-up handy, you weren’t competitive.”

This craze caught the attention of Sports Illustrated and the August 13, 1973 cover featured a young blonde-headed boy sitting atop a snippet of a motorcycle and wearing a concerned look on his face. The boy was Kurt Henricksen, son of Ron Henricksen, who founded the NMA (National Motosport Association), and promoted must-do events such as the World Mini Grand Prix and the Ponca City Grand National Championships. Although Kurt’s bike said “Indian” on the gas tank, Ron said it wasn’t. He took a decal and applied it to the tank. The frame was a Bonanza with a one horsepower “Torgi” engine. “I wanted to make a bike that looked like a real motorcycle,” he says.

Kurt’s red sweatshirt, jeans, white socks and low-cut brown boots looked more like an outfit for the first day of Kindergarten. The cover line above the photo read “Too Much Too Soon?” and the story inside – written by Ernest Havemann – mostly focused on the ridiculous quest parents go through to fill their kids’ bedrooms with trophies. Havemann talked to parents about racing – the costs, the modifications, danger, cheating – and, in the end, determined that they wanted to win more than the kids did.

Around the same time period, on the other side of the country, Bill Griffin didn’t have the engineering skills of Rudy Dickinson. He owned a roofing business and co-founded the Mid-Atlantic Motocross Association (MAMA) in 1975. He also promoted District 7 motocross races in Aquasco, MD and grew tired of seeing his own kid get beaten on uncompetitive machinery. “At that time, if you didn’t own an Italjet, you weren’t competitive,” he says. In 1976, when the Italjet X50R became available, he shelled out $1000 to purchase one and then another $1000 to overnight ship it from Los Angeles to Baltimore. They needed it for a big race that weekend.

“The only people who had the Italjet bikes were dads with money,” said Randy Bradshaw, whose oldest son, Damon started on a Honda MR50. “We were just local, average people.” They raced in the Gastonia, NC region starting in 1975. Randy remembers sparse participation at motocross races in their area. “There were five or six kids that rode motorcycles and they didn’t even divide them into age groups. You’d go to a local track and there may be 50-60 bikes total for the whole event. The little ones fell all over the place and the parents sweated more than the kids did.”

This loose program forced Griffin into action as an organizer. “We started MAMA because the youth racers always got a raw deal,” Griffin says. “They’d run out of time and just run the kids around an apple tree or something like that. We got laughed at because they said there would never be enough youth riders to keep it alive.” But Griffin felt parents wanted something better and he ran ads in the Washington Post asking if anyone had interest in getting their kids involved in motocross.

“I put my phone number in there and it rang off the hook,” Griffin says. “We got Tony Distefano and Gary Bailey to come put on clinics.”

The New Kid

The PW50 wasn’t supposed to be the motorcycle that homogenized the pee wee class at every amateur motocross race in the world. It wasn’t developed or classified as a competition race bike. It still isn’t. But this is the natural progression, right? The first motorcycle race happened when the second bike rolled out of the factory, so goes the story.

And Motocross Action predicted it in their January 1981 issue where they cheekily wrote about minicycle racing being “a classic case of children victimizing adults. The Yamaha YZinger… will probably become the mainstay of the class because of its maintenance-free construction.”

“In 1981, I remember a huge number of PW50s showing up,” says Ian Riley, whose father opened Frederick, Maryland’s Fredericktown Yamaha in 1975. Riley grew up racing around the Mid-Atlantic in the 1970s and 80s. “The 50cc class went from a dozen kids to full gates. By 1983 some events had separate divisions, A, B and C.”

At the 6th annual NMA Grand National Championships in Ponca City, Oklahoma, the new Yamaha far outnumbered entries from Italjet and Suzuki and claimed three of the top five spots in the pee wee stock championship. Colin Edwards, future 2-time World Superbike Champion, won over Ronnie Densford. Both rode YZingers.

The dads, of course, couldn’t help themselves. They found ways to make the little shaft drive trail bikes ridiculously faster almost immediately. Promoters had to offer stock and modified divisions for the class. The easiest modifications were simple: plug the autolube oil injector and run mixed gas directly in the tank. Also, drill holes in the airbox for increased air flow. Those gave an innocent but effective little boost.

Then came the comically bulbous cone exhaust pipes that made the bike sound like chain saws. The handiest fathers didn’t stop there. Ronnie Densford’s dad jacked his up with suspension from a YZ60 and ported the cylinder among other mods. Mr. Densford started RD Racing products and sold an entire catalog of bolt on kits and offered engine services.

Robert Reynard Sr. got very creative for his son, Robbie. He cut and lengthened the swingarm and driveshaft and converted everything inside the motor from bushings to bearings because he didn’t like how much drag the bushings created. He used bigger cylinder heads and fabricated new parts out of aluminum. “I built a completely different bike,” he says. “We could do whatever we wanted in the modified classes back then.”

His wife is still mad about the vacuum cleaner he ruined. He wanted to see the flow pattern of the ports so he could measure the velocity of the air coming up the head. So, he took the family’s Rainbow vacuum cleaner and made a flow bench out of it. It ruined the machine’s ability to clean floors but Robert got several good years of motor work out of it.

His wife saw value in what he did and suggested he start up his own brand of pee wee motorcycle. “Nobody would buy these,” he remembers telling her. Ultimately, she was right. But it took over a decade of domination before another brand proved competitive at the highest level of amateur motocross.

In 1982, the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championships took up residence at Loretta Lynn’s Dude Ranch in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. That’s where the PW50 started a 12-year run of championships. That first title, however, came by way of disqualification. Billy Schlag won on a Suzuki JR50 but got protested by second place, Butch Smith. Although the 50 class allowed modifications that year, officials determined Schlag’s cylinder to be slightly over bore. Schlag said his father swore the motor was legal until the day he died in 1993. But the appeal letters didn’t sway the American Motorcyclist Association and Smith retained credit for winning the title.

Schlag was more worried about possibly not getting a new BMX bike than he was about the disqualification. On the way to the race he made a deal with his dad: victory equals new BMX bike. Mr. Schlag still came through.

“I think the dads were into it more than we were,” Schlag says today, with a laugh.

The PW50 dominated the class and took up nearly every single gate position at every major amateur race around the country. In 1991, however, the Italjet “Buster” showed up and proved to be a lighter, faster, and formidable machine.

When it stayed running.

My parents imported those Italjets to their shop and sold one to the family of Dewitt, Michigan’s Jerod Whipple. A young riding partner of Nick Wey, Whipple had top three speed in the 50cc class but for three consecutive years (1991-1993) bike problems marred his overall placing. The most painful happened in 1993 (2-2-31). I watched from the fence as Mr. Whipple vented his frustrations. That same year, Ryan Sipes experienced a similar fate. In the very first moto, his Italjet quit moving in the first corner. When the bike cooled off he rejoined the race two laps down. “Faster and better than a PW,” he says today over a text message. “WHEN THEY DIDN’T QUIT! I think the stator was going bad or something.”

In 1993, the 50cc class split into two age groups, (4-6) and 7-8) and in 1994 the PW50 streak ended when the controversial but very fast Cobra and LEM motorcycles arrived into the class. Haines City, Florida’s James Stewart failed to defend his title. Officials disqualified Stewart from moto one when “his father crossed the track to help him with a badly coughing motor,” reported Davey Coombs in Cycle News. Stewart won the final two motos but the title went to Ohio’s Brett Maimone, whose father, Bud, created the Cobra.

Yamaha never regained its stranglehold at the 7-8 year old level of 50cc racing but it chugs along in the (4-6) Stock Shaft Drive class, which started in 1998. Through August 2020, the bike is 23-0; Yamaha’s PW50 has won 36 titles at Loretta Lynn’s alone.

Pee wee class domination on any brand, however, doesn’t equal professional success. Of the Loretta’s champions who rode PW50s to victory between 1982-2020, only two have ever won races in AMA Pro Motocross/Supercross: James Stewart (1993) and Cooper Webb (2002). Factor in all of the 50cc champions in the event’s history (102 total on Yamaha, Cobra, KTM, LEM), only six have ever gone on to win major races professionally: Stewart, Webb, Davi Millsaps (2), Austin Stroupe and Adam Cianciarulo.

Leave It Be

Not many products go largely untouched for four decades. Even the breakfast cereal I enjoyed as a kid tastes different. Maybe it’s because I’m not crunching through the molars of a 12-year-old but somebody screwed up the formula for Kix.

The PW50, though? It’s manufactured from the same molds. Outside of colors and a few bodywork adjustments, only the suspension has changed. The gas tank and fenders got slimmer in the mid-1980s. Then the YZinger nickname disappeared. In 1997 the front and rear suspension switched from grease to oil-dampened. And 20 years after that, the forks got bigger inner tubes and aluminum outer tubes while the rear suspension got a bigger cylinder rod. And, of course, in the United States, the bike went from yellow to white and now blue.

Yamaha didn’t change the bike for four decades on purpose. “The role of the PW50 in Yamaha’s lineup is to introduce as many kids to motorcycling as possible and grow our motorcycle industry for the future,” says Yamaha’s Off-Road Motorcycle Sr. Communications Specialist Mike Ulrich. “Keeping the price point as accessible as possible is crucial. We could update styling and/or function of the bike, but that would mean incurring development and tooling costs that would result in a higher retail price point.”

That doesn’t mean a PW50 is cheap. The cost of a 2021 model increased 10% from 2020 to $1649, the first price jump since 2018. Over 40 years, the PW50 increased in price 375% from $439 in 1981. That’s less than its teenaged brother though. Over the same period the YZ125 increased in price 440% from $1499 to $6599. That bike is radically different today but its last overhaul came in 2005.

The newest PW now costs more than the YZ125 did in 1981 ($1499). Yet, it’s still cheaper than an Apple iPhone 11 Pro Max with full capacity and damage/loss coverage ($1718 + tax).

In fiscal year 2019, the PW50 sold 8,200 units. In 2020, when pandemic-weary parents emerged from COVID-19 lockdowns in the spring, they wiped out dealerships of bicycles and motorcycles. I called dealers around the country. Many went months without any type of kid’s bike on their showroom floors. Glen Burnie Motorsports in Maryland said they sold a total of 220 motorcycles per month during the spring and early summer, up from a historical average of 100 per month.

When the 2021 PW50 models arrived in showrooms, they too disappeared. Josh Voth, the Chaparral sales manager, said he unloaded all six of their 2021 PW50s by early September. He’s praying to get more by Christmas. Meanwhile, Freeride Powersports in Ann Arbor, Michigan received a message that their 2021 models wouldn’t arrive until November. And Fredericktown Yamaha is waitlisted; they only get one if another dealer gives one up.

It doesn’t net dealers much profit. Two dealers told me after freight and setup charges, their shops make under $100 per unit. One said $82, specifically. “You’re not selling them to get rich,” says Ian Riley of Fredericktown. “You’re trying to start a habit.” Habits come with other expenses that do help dealers, such as protective gear, tires, oil, etc.

The bike still does what it was intended to do; it introduces new riders to the trails and tracks. Motocross Action named it the most innovative production bike of 1981. The PW50 was so innovative, Yamaha left it alone for 40 years.

My Story is Your Story

“Why in the hell did you buy a three-year-old a motorcycle?” my dad remembers someone asking him after we brought the bike home in the winter of 1982. I visited the garage a lot that winter. The little yellow and black bike looked tiny next to the 650 Special my parents rode. I practiced rolling the throttle on and off. Dad had a rule: if you can start it, you can ride it. That spring, while weeding a garden bed, he heard the ‘chug, chug, chug’ of the YZinger. I learned the next big lesson the hard way: pay attention while riding.

It wasn’t the first ride, maybe not even the second, but during the summer of 1983 I raced across the lawn with my head facing in the wrong direction. I smashed into the bottom of our playground’s slide. Bike and body went airborne.

It was bad.

I wasn’t injured but the bike sat in the garage for a spell before I got comfortable on it again. We raced for the first time at Baja Acres in Millington, Mich. in September 1984. I got second. Two riders registered that day. For 1986 we traded in that yellow ’81 model for a brand new white and red one and qualified for the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championships at Loretta Lynn’s. The most noteworthy name to come out of that class three spots ahead of me; Ronnie Renner Jr. took 22nd place.

One year later, at the same event, we competed on the PW for the final time. I was a wiry eight-year-old, tall enough to knock my knees together above the seat and that poor bike spent a lot of time on the hot end of a welding wand. And I spent more time on a Kawasaki KX60. Unabashedly, I wore green Hallman riding pants with Kawasaki down the legs even while competing in the pee wee class. To really showcase your forthcoming graduation from the automatic class, everyone who was anyone ran the green thumb decals that Kawasaki Team Green handed out at the races. At the time, Yamaha and Kawasaki had the only competitive motorcycles in the two smallest divisions of motocross. We all knew where we were headed.

That’s my story. At its core, it’s probably not much different than your story. Most motocross riders born around 1975 and later can find pieces of their own story inside mine. And it’s all because of the PW50.

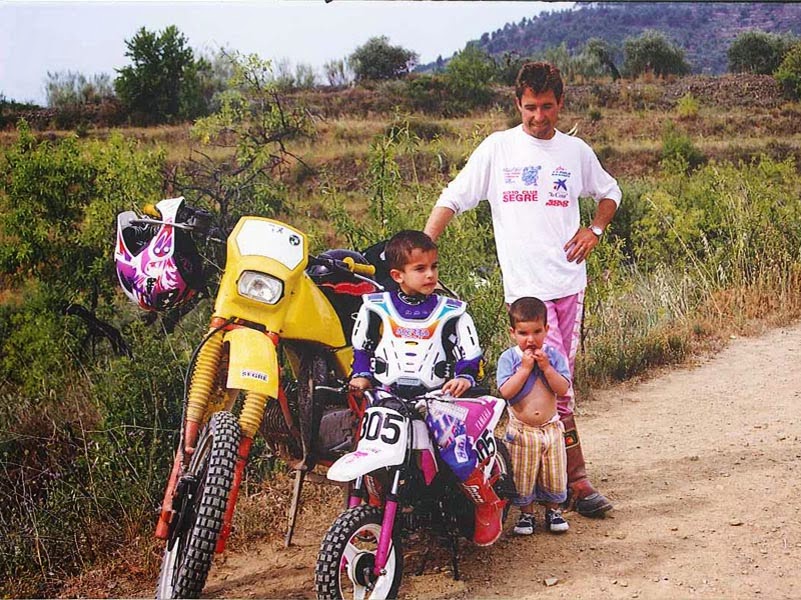

That’s why Renner bought his kids PW50s when they were ready to ride. So did Supercross and motocross champions Chad Reed and Ryan Villopoto. Childhood today looks different than it did in 1980. Technology changed drastically, attention spans eroded and the cost of riding outpaced inflation. Kids and parents also have more choices for entertainment. But the PW50 didn’t change. For those of us who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, it’s the one piece of our childhood we can pass to our children that still looks, feels and sounds the same.