Doug Henry and The Dam

By

Officer Schick (not his real name) has good reason to arrest all three of us. Or at least detain us. He’s busy responding to the scene of a minor traffic accident when he spots us riding up Connecticut Route 34. We take a driveway that forks off the road but he breaks from the accident to climb an embankment and block us.

There’s no denying that we are attempting to trespass. It’s also an area where high voltage overhead power pole work happens daily. Schick is both amused and annoyed and he takes particular interest in one member of our three-man crew who rides a funny looking bike with no seat. As I sit on the back of a camouflaged utility ATV, clutching both sides of the rack, Doug Henry sits at the controls. He explains why he needs to get onto this property.

Doug wants to wear down the patrolman. I keep quiet and so does Doug’s friend who is next to us on a trials bike. Schick laughs. He can’t figure out what’s funnier, the fact that these three knuckleheads are riding off-road vehicles on paved secondary roads or that they think they’re going to get on this property, a rock quarry across the street from Oxford, Connecticut’s Stevenson Dam.

Henry doesn’t let up. He has talked his way through this situation his entire life.

After school on weekday afternoons, Henry and his friends rode for five miles on a network of trails, paved roads, backyards and railroad tracks, down Route 34 and across Stevenson Dam to ride at a place they simply called The Dam.

This is the spot that made Doug Henry into a championship caliber rider and I want to see it. It was illegal to ride there in the early 1980s and it’s still illegal today.

New England Legends!

Yet, if Henry hadn’t discovered this crude New England gem across the street from the Housatonic River–if he had folded the first time the cops ran him out–there’s a good chance he would have become just another weekend warrior on the New England Sports Committee series.

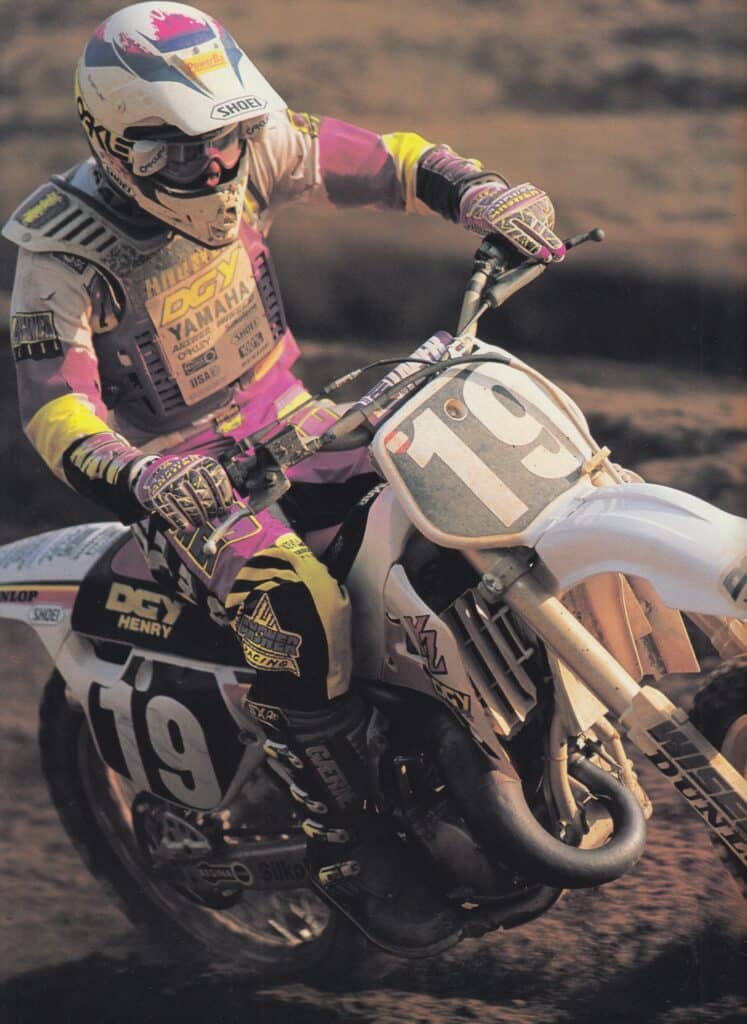

Instead, Doug was as relentless as the whoops and rocks that fill the quarry and he became a three-time AMA Pro Motocross champion, an X Games gold medalist, a member of the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame, a pioneer, a hero and a national treasure of American motocross.

But Doug Henry is the most determined person you’ll ever meet and it’s clear he’s not going to stop talking until Schick moves out of the way.

Who is Doug Henry?

Douglas Arthur Henry grew up in Shelton, a town in southwestern Connecticut whose industry has seen more robust times. His father, Bill was a machine fabricator with Sikorsky Helicopters and his mother, Beverly was a grocer.

Doug was the youngest of three. His sisters had horses and he got a 2.5 horsepower mini bike at age four. He wore an eight-inch wide trail around the entire house, a path that got more broken in when he graduated to a YZ80. That’s when Gary Morrison remembers seeing him. Morrison, a neighbor, cut through Bill Henry’s 10 acres on his way to The Dam. Doug’s speed on the little trail impressed him.

“I’d just watch him ride in his yard and I said, ‘Man, you should go racing,’” Morrison said. “I told him he should go up to Southwick and watch the races and get into it.”

Doug credits Morrison for that push but he didn’t make it to Southwick for his first race until 1984 when he was 14. He became a top NESC racer, won his first title in 1988, but harbored no expectations of a future in motocross. They didn’t buy a motorhome and trailer, didn’t travel to Ponca or even the AMA Amateur Motocross National Championships at Loretta Lynn’s.

Motocross wasn’t the only thing in his life but it was what he loved the most. He played hockey in the winters and as an adult he joined a men’s league to stay active. Henry loved racing so much that, starting in 1987, he binge-worked for weeks at a time to save enough money to get out of New England and race the Winter Series in Florida.

One year he logged 16-hour long days between two jobs: loading UPS trucks and welding. He also did work in machine fabrication and sheet rock. In Florida, he slept in his van, ate rice, cereal, peanut butter and jelly on hot dog buns and soup from the can. And the most peculiar part is that he wasn’t trying to make a career out of racing.

“This is all like a big vacation to me,” he said in a 1993 Inside Motocross interview. “I’m just waiting for someone to come along and say, ‘That’s it, you have to go back to work now.'”

Support We Went Fast!

His father supported his son’s ambitions but was still skeptical. When Doug turned 18 in September 1987, the financial responsibility of riding and racing shifted to Doug. Bill helped him keep the bikes running, made and fixed parts and occasionally came to the races but deep down he felt like his son should be working a normal job.

“He wanted Doug to work at McDonald’s,” Stacey Henry said, recalling a phone conversation Bill had with Doug while he was living out of his van in Florida one winter. She remembers sending care packages to him in Florida while they were dating. Doug and Stacey were married in 1993.

“I was so proud of him getting out of the valley and trying to compete because all he knew was New England,” she said. After his annual trip to Florida concluded in 1990, Doug didn’t come home right away. He went to the supercross races in Dallas and Pontiac first. Stacey, who had recently earned her degree in graphic design, spent that winter as a ski bum. She met him in Dallas. They were broke but had fun.

“I loved it because it was such a testament of what you really need,” she said. “You live so simply and you do what you love and life is pretty good.”

They heated up their rice and soup with a Coleman camping stove, slept in the box van in parking lots and even slipped into hotels in the mornings where they would bribe the chambermaids with a few dollars to let them shower in a vacant room.

“You don’t have to tell that story,” Stacey said to Doug, half wincing.

“But we were quick!” Doug said with a smile, seeking justification.

They sought out the Yamaha box vans after the race so they could collect any discarded items–plastics, chains, sprockets–from the factory mechanics. A Damon Bradshaw number plate still hangs in Doug’s old garage. The Henry family didn’t waste; fix it, reuse it, make it last.

He couldn’t afford to buy Paul Buckley’s photographs when he raced local New England Sports Commission (NESC) events. Doug went as far as combing the track after the race for tear-offs that were clean enough to be reapplied to goggles. “It was a bonus when someone pulled them all off at once! Huge score,” he said.

In the summer of 1990 Doug said he almost had to borrow money. He was on financial fumes at a race but he took the last transfer spot and earned enough money to continue. “I just wanted to qualify,” Doug said. A hundred bucks got me to the next race.”

These were the moments Dave Arnold, Honda’s Team Manager, noticed in the early 90s when he was shopping for a 125cc rider. Bevo Forti told Arnold to vet Henry. The details of the time and place are fuzzy but Arnold specifically remembers observing Doug in the pits at a race. On a wet, miserable day, Doug pulled his bike out of the trunk of what Arnold remembers to be a small rusted Chrysler. He had no crew on hand, not even a friend.

“I watched him in the drizzle take the thing out and he just seemed happy to be participating in the sport,” Arnold said. “He was just into it. He went out on the track and did a good job. The bike had bent bars, bent levers, jacked up grips. At the time I think he did a lot with very little.”

Doug’s entire life story can be linked together with anecdotes about making do with what he had not wishing for something better. Henry never blamed the tools. He always blamed the carpenter. One of his tools? The Dam.

Doug Henry Gets Five Minutes

The bespectacled young woman who smashed up her car stands on the road below us with an ice pack pressed against her cheek. Officer Schick must sense her glare because he turns to her and says, “Have you called your mother yet?” She nods.

He turns back to Doug and says relentingly, “Five minutes. And have someone come pick you up. Do not get back on the road.” We’re in.

The Dam is a chaotic network of whooped out and rocky trails and berms that intersect and collide. Wild olive bushes choke the path because the track isn’t maintained. Most of the course is just wide enough for the ATV Doug rides. He has not been here since he was paralyzed in 2007 and he remembers it being much more open, not as congested with shrubs and branches. But still, many sections of the track have not changed and he points out a rolling incline whose path disappears into the Ash trees.

“This is where I thought of Stanton,” he says.

“Jeff Stanton?” I ask.

He says his imagination wandered while he rode. On tough sections of the course he thought about racers he admired. He felt that if he could get through that section well lap after lap then he would get stronger and faster. He still remembers who he thought of on the course and where. By the late 80s He had to imagine because his riding partners no longer challenged him.

“If you were outside the rock quarry you knew Doug was riding his 125 because the sound never shut off,” said Ron Lombardi, a childhood friend. “He was wide open the whole time and it was not the traditional sounding ‘rev, shut off, clutch, shift, rev’. The only time it got quiet was when he was in the air and then the ground would literally shake when he landed. No joke.”

Not even ‘The Godfather,’ local fast guy Bruce Hawes could keep up. Hawes lived across the street from the track.

“Bruce actually had numbers on his number plates,” Doug said, as if that gave Hawes some kind of extra certification. Hawes remembers his first encounter with Henry. In 1984 he bought a new Kawasaki KX250 and saw a teenager on a YZ80 at The Dam. He showed the young man a lap around the track. Being a rock quarry, the endless options for design and layout changed weekly.

Bruce actually had numbers on his number plates.

–Doug Henry speaking of local fast guy, Bruce Hawes

After that one lap he “Stuck to my ass and I was amazed at how fast he was,” Hawes said. “I had to push just to get away from him and he was on a little 80.” Hawes recalls young Henry coming over to his house to ask him how he was able to ride for so long on the rough track. Doug wanted to soak up as much knowledge as he could.

Doug loved these tips. He wanted to know everything he could about getting faster, better. “Everyone else was just happy to get out and ride,” Stacey said. “He had this appetite, ‘More, how can I improve?’ He had this passion that wouldn’t quit.”

Maybe it’s because most of the guys who rode at The Dam were on 125s, 250s and even 500s and he wanted to keep up. Maybe he was tired of being blasted by rocks the size of hand grenades. He simply wanted to be faster and he tried every tip and trick he could get. He fastened his fingers to the levers; used a 2 x 4 on his seat to force him to sit forward; taped off the bottom of his goggles so he had to look ahead and not down. When the master brake cylinder of his 1989 YZ125 blew, as they often did, he didn’t ride home. He learned how to ride faster with only front brakes.

“You crash and you break a clutch lever, you’re not swapping a clutch lever out, you’re riding the rest of the day without a clutch lever,” he said. “Bent bars? You’re riding the bike because it was so far to go back and forth so you rode with what you had.”

Riding at The Dam looks like a cruel experience to outsiders. It doesn’t get groomed and the whoops look like Southwick after a professional race. The squared edges catapult riders. The rocks break fingers and the course is so narrow that passing possibilities only come to the most creative of riders. The spiderweb of trails intersect and merge so if a rider shows up during a session and doesn’t check in, collisions happen. On the scale of motocross track quality, it ranks between suffering and hell. But if a rider can master this place, anything else is like fresh blacktop.

“It was all I knew,” Henry said. “Other than a trail in the woods, as crude as it was, that was the closest thing you could get to a track to ride on. That’s all we really had.” Stacey likes to tell the story of Doug bringing his Honda and Yamaha teammates there to ride even if she feels like the memory might be slightly exaggerated today.

“They didn’t want to ride it after five minutes,” she said. “They talked about how difficult it was and how harsh it was.”

Doug Henry Gets a Wing and a Prayer

In the early 90s, Doug bought a piece of property nearby where he had a trailer and a small supercross track in the front yard. “Terrafirma”, the first installment of the popular Fox Racing video series, opens with a scene shot here. The Dam had become so instrumental to his program that he got special permission from landowners to ride there. He rode there frequently until 1999 when he moved an hour north to Torrington. After that he made only an occasional appearance.

When he signed with Honda in 1993, Henry thrived and won the 125 Eastern region supercross title and two 125 Pro Motocross titles (93-94). After nearly five years as a privateer and working odd jobs to pay for racing, being teammates with Jeremy McGrath and Jeff Stanton at American Honda wasn’t a total relief.

He knew he had the best equipment available and he wanted to keep what he earned. He viewed the one-year deal as a positive. It forced him to work harder to get a renewal. He also admits he had no idea how much effort teams put in to win. He remembers 12 guys hovering around his bike at the first test session. “I wasn’t only winning races for me now,” he said.

Henry soaked it all up. He loved testing. Having a bike set up just for him seemed incomprehensible. Doug didn’t even wash his bikes as a privateer. He and his dad pounded out dents in the exhaust by hand, they made shock bladders out of coffee cans, fabricated an enlarged 50-tooth sprocket in order to get more life out of a stretched chain. He used to get satisfaction from being the guy who beat the riders that showed up to the track with crisp gear and a trailer full of new bikes. Now he was that guy.

“You could give Doug some advice and he would take it and he could process it and he could work with it,” said Pete Steinbrecher, Henry’s mechanic at Honda. Steinbrecher followed Henry to Yamaha in 1996 because, “He’s Doug Henry. I was never going to get another rider like him.”

Henry liked working with Steinbrecher for the same reasons that Steinbrecher liked working with him. As a privateer, Doug noticed Steinbrecher. On the road, between races, he woke up early for runs and saw Steinbrecher outside a Honda box van working on a bike. He felt Pete put the work first and he secretly hoped that they’d team up someday.

Doug quickly became a fan favorite and not just to the people in New England. Everyone noticed his work ethic and obvious love and appreciation for racing and life. When he broke his back in 1995 at Budds Creek he realized how much he affected the lives of some of his fans. They showered him with cards and letters. When he felt low, he read through them.

The 1995 Budds Creek crash

“I got so many letters from fans and people I didn’t know,” he said. “Maybe I gave them one little signature, a ‘hi’, or a shake of a hand. That little bit of time you spend with someone, you don’t realize how much that means to them. Those letters really brought me back and helped me out in a time when I needed them.”

His long comeback from the back injury, having the guts to try a four stroke motocross bike, and coming back from the double wrist injury in 1997 to win the 1998 250 (now 450) Pro Motocross title earned him hero and legend status in the eyes of his fans. Even though he was always grounded, Stacey found it difficult to share her husband like that.

“Underdog. I won’t call him a hero,” she said. “Nobody saw who he was. Then, all of a sudden, the world caught on and, yeah, it’s hard to compete with the affection of the masses.”

In 1990, Bill Henry pulled Stacey aside and said “Stacey, the bikes always win.” Stacey remembers exactly where she was when she heard that. “Bill felt obligated to explain to me how Doug was,” Stacey said. “I appreciated that.”

Stacey and Doug divorced in 2017 but still live near each other in Torrington. Their children, Ian and Brianna, are grown and out of the house. Seeing them together it’s clear that they still care about each other very much.

When he retired from full-time professional racing after the 1999 season he and Stacey tried to be gentleman farmers. Doug couldn’t stomach slaughtering the pigs and they quickly determined that he wasn’t very good at farming. On a scale of one to ten, Doug gives himself six tenths of one point.

“Wow,” Stacey said laughing at Doug. “I would have said three.”

When asked what happened to the farming dream, Doug quickly raised his fist in the air as if taking a victory lap and said, “Supermoto came along!”

“Aren’t You Doug Henry?”

Doug often smiles but his grin meter nears a 10 as he bench races with his friend Jim Barlow, who straddles the Beta trials bike while we take in the sights of their childhood riding area. Doug mimics the motions of a motorcycle working a rough section as they talk about how they used to ride at The Dam. When Henry moved to Torrington, Barlow bought the Oxford property. Doug likes it because it keeps alive his connection to this area. Paralyzed since March 2007, Doug still rides motocross on his modified YZ450. The Dam, however, is much too rough.

The rain that threatened all day starts to fall lightly and we make our way to the exit. Three power pole workers who had been watching us approach on foot. Doug apologizes and says we’re leaving.

“Aren’t you Doug Henry?” one of them asks.

“I am!” he says.

“See, I told you that was him!” another one says, jabbing his co-worker.

They gather around the ATV for a photo. Doug offers his ball cap in exchange for a construction hard hat.

Snap.

With the closing of a shutter, three young men from New England can prove to their buddies they were last people to ever see the legend Doug Henry ride at The Dam.