The Darkest Day in Motocross

By

On August 1, 1982, an automobile/train collision killed three teenaged motocross riders in Ponca City, Oklahoma. Decades later, memories of that white hot afternoon still haunt those who were there.

Team Suzuki’s awesome three,

The best damn riders meant to be.

They were friends, teammates and out for the winning,

But the tragic day at Ponca was the end of the beginning.

They were chasing their dreams, doing what they did best,

But now the incredible three are put to rest.

–Excerpt of a 1982 poem by 12-year-old E.T. Taylor.

Memories fade. They get foggy or faint; sometimes they fizzle and can be fickle or fleeting. Too often they simply fail. While everyone remembers where they were during a highly emotional event (say, September 11, 2001, or JFK’s assassination), the details surrounding it can warp over time – even when one was directly involved.

There are over a dozen types of memory errors, from false memory to bias, intrusion, misinformation, absentmindedness and transience (forgetting over time). When a memory isn’t periodically reinforced, it gets boxed up, packed away and sent into a mental black hole.

Also available as a podcast

For those who attended the 1982 NMA Grand National Motocross Championships in Ponca City, Oklahoma, the afternoon of Sunday, August 1, is one of the most unforgettable of their lives. Yet, everyone remembers what happened a little bit differently. Some wildly differently.

Nobody at the four-day event witnessed the accident that happened one mile east of the racetrack; the accident that took the lives of three of the sport’s best minicycle racers: Bruce Bunch (16), Rick Hemme (16) and Kyle Fleming (13). The legend and the rumors about what happened in the Mercury Lynx wagon driven by Oakley’s Dana Duke have grown. When people discuss it today, it sounds like they think they witnessed… something.

What we know for sure is that at 4:43 pm on August 1, Bunch and Fleming died instantly. Hemme died in the hospital nine days later, and Duke spent two months in a coma with slim chances of survival. He lived, but decades later is still undergoing surgeries and suffering complications.

It’s the darkest day in the history of motocross, and even though these teenagers became faster with the passing of time, for many, there’s no doubt that the motocross record books of the 1980s and 1990s are missing three names: Bruce Bunch, Rick Hemme and Kyle Fleming.

This is the untold story of their lives and deaths.

Bruce

In Orange County, California, a 1982 Toyota 4×4 SR5 still rolls down the roads. It’s a manual shift pickup, with a long bed, AC, tilt seats and only 93,000 miles on the odometer. The license plate is the classic California blue with embossed yellow letters that spell “BUNCH 1.” Even though the original owner never got his driver’s license, he drove it to riding spots all over Southern California.

He had been driving since he was 10, when his mother taught him how to use the stick shift of her Toyota Corolla and let him buzz across the dry lake beds at El Mirage while sitting on a stack of pillows. Friends today swap stories about switching seats with him in the truck when police officers popped up, because of his being unlicensed.

Michael Bruce Bunch was an only child, fiercely independent, sarcastic, witty and determined to be a motocross champion. He was so competitive, he kept his best friends in the dark about some of his training routines and methods, even if they were in different racing divisions. He didn’t want anyone to know that he ran eight miles roundtrip from his home in Orange, California, to a park on the corner of Lincoln and Tustin – wearing his motocross boots.

His mother, Anne, took him practicing twice a week at Saddleback, and when he overheard her in the pit area telling another father their schedule, he admonished her. He didn’t want anyone to know how much practice time he got. He did, however, like to show off his one-armed pushups to his friends.

“He was very disciplined about exercising,” Anne Bunch says. “More than any adult I’d ever met. He did everything you should do to be an athlete. When he was really little, he would do exercises while I was doing them. He would copy me.”

Bruce was a precocious, curious child. Anne says he walked at nine months and rode a bicycle at three, skipping the training wheels phase entirely. His elementary physical education teacher marveled at his ability to run through the school’s obstacle course. He was uncannily coordinated, like a deer, Anne remembers the teacher telling her.

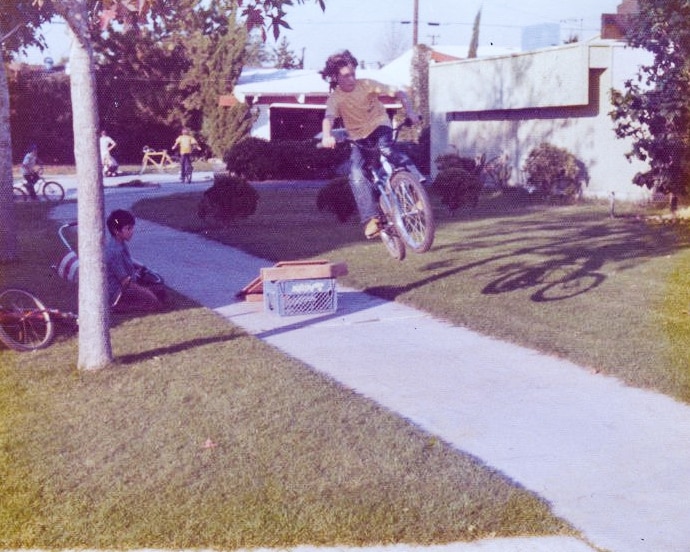

When the neighborhood daredevils set up the classic milk crate and wood plank jumps on the sidewalk, Bruce was always the first one to test it, especially when the ramp was pitched higher and higher with blocks of wood. He broke the frame on nearly every bicycle he owned.

The sarcasm ran thick and the jokes and pranks plentiful with Bruce around. He could disarm a bully with his wit, and with his humor make milk come out his friends’ noses. The most common victim of his mischievousness were his father Ralph’s smokes. He’d poke holes in them with an ink pen or drown the pack in water or Coca-Cola, drain it and put it back on the table. It enraged Ralph, especially when he was stuck at the racetrack all day with no cigarettes. Today, it’s a fond memory for Ralph and he chuckles when talking about it.

In January 1977, as 5th graders, he and his friend Ron Rogers competed at Escape Country MX, their first race. Bruce rode a Yamaha YZ80 and took second in both motos. Rogers remembers being back in 30th place out of 35 kids. Bruce progressed quickly. He picked up support from Harry’s Cycles in Orange; he won a Kawasaki KX80, and then a dealership in Santa Ana gave him 40 percent off parts.

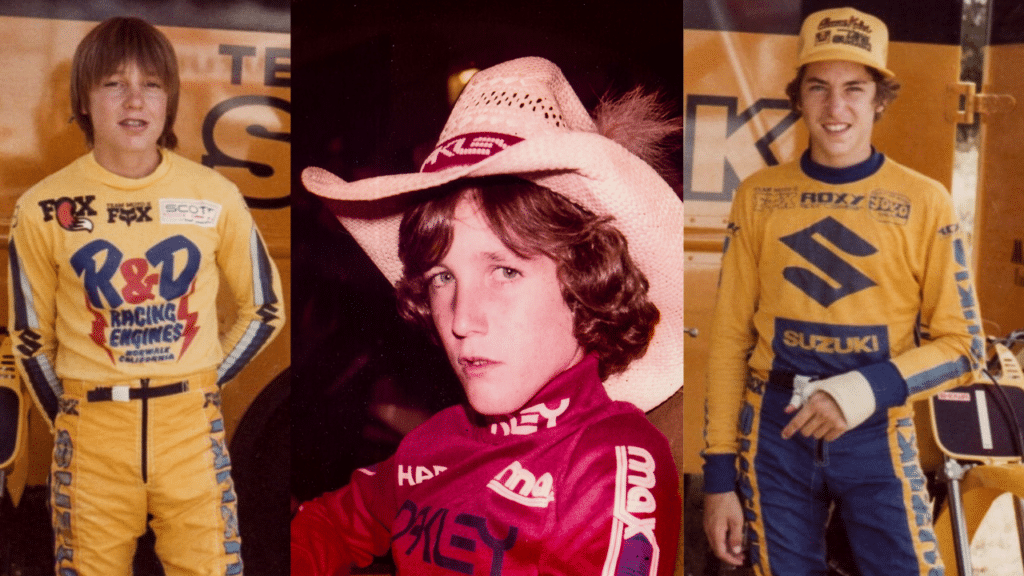

For 1981, he received a coveted spot on Team R&D Suzuki, the same company that brought up Ricky Johnson. He received seven bikes a year, his engines and suspension were handled by Rudy and Dean Dickinson (the ‘R’ and ‘D’ in R&D) and an unlimited parts allowance.

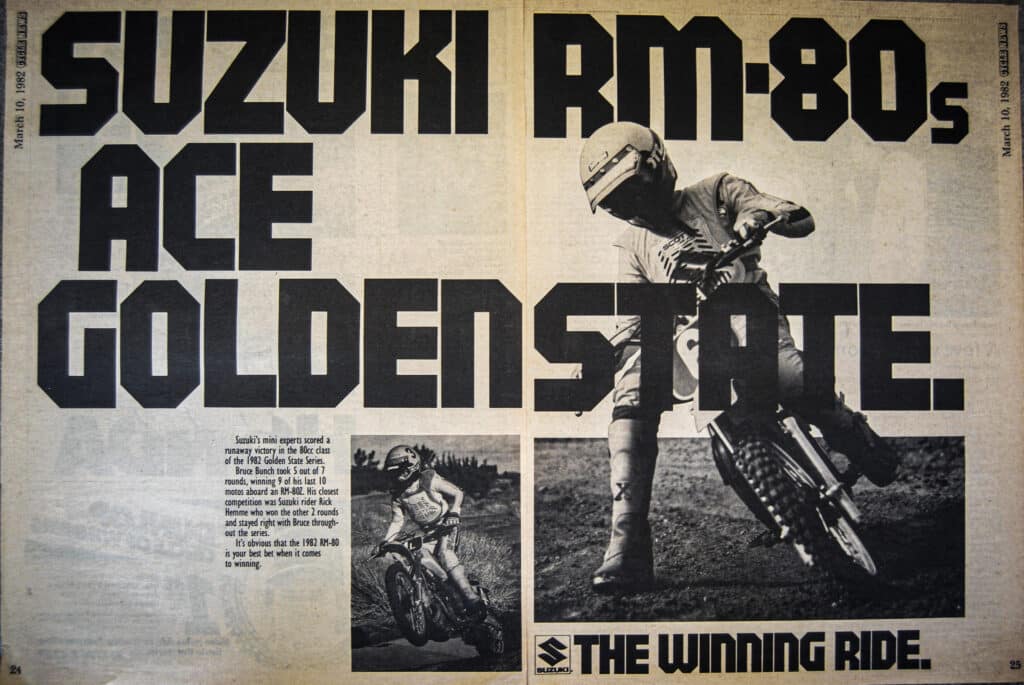

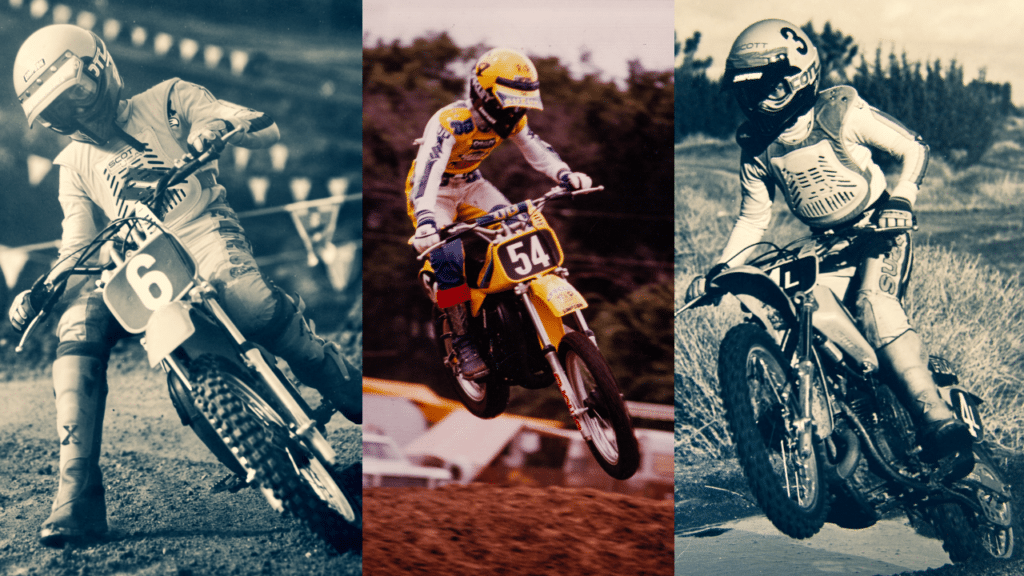

Bruce continued to improve and in 1982 he really broke through. He won two of his three classes at the NMA World Mini Grand Prix in April, and before that he won the seven-round CMC Golden State Series championship in the 80cc expert class over his teammate Rick Hemme. Competing at the CMCs put him in front of the professional factory teams and riders who used the Southern California-based series as a warmup for the AMA Supercross and motocross championships.

Johnny O’Mara used to go to the fence between his own races to watch Bruce, Hemme and other minicycle riders. He liked to see the lines they chose. When Bruce received coaching from professional rider Brian Myerscough, Ralph noticed his son improving dramatically.

“Brian taught him how to go around corners with his feet on the pegs,” Ralph says. “He picked up good habits from him. Bruce could read a track well. He was a natural.” Ralph spoke to both Suzuki and Yamaha about pro contracts for 1983. “That kid had the potential to rewrite the history books,” says Dean Dickinson.

The NMA Grand National Championships were once again in Ponca City, Oklahoma, in late July 1982, and Bruce vowed to make it the last minicycle race of his career. Three weeks prior to the race, however, he crashed while chasing a rabbit in Lancaster, Calif. He had driven his Toyota pickup over 100 miles by himself to ride with brothers John and Rick Hemme. He suffered a minor fracture in his left wrist and asked sports medicine specialist Dr. Glenn Almquist to make him a cast that would allow him to ride. Almquist kept handlebars in his office for his motocross patients. They held onto them while the casts dried and formed.

Anne didn’t want Ralph to take Bruce to Ponca and still harbors resentment over the decision to go. She had made an appointment for Bruce to get his driver’s license and, of course, he had a broken wrist. Anne didn’t attend races at all. She supported Bruce but didn’t enjoy seeing all the pressure other parents put on their children, so she stayed away. Instead, she flew her Cessna 150 over Saddleback MX Park on weekends to check in on Bruce. She loved to fly but didn’t start until Bruce was a teenager; he was her first passenger.

Divorced since 1978, Anne and Ralph shared custody and lived 12 miles from each other. Ralph doesn’t remember being asked not to go to Oklahoma but, “I’m sure she did,” he says today. “[Bruce] was on top of the world, and he wanted to go be with his friends. The doctor said it would be OK, or I wouldn’t have gone.”

In a phone call before he left, Bruce tried to reassure his mother.

“I’ll be OK, Mom.”

Kyle

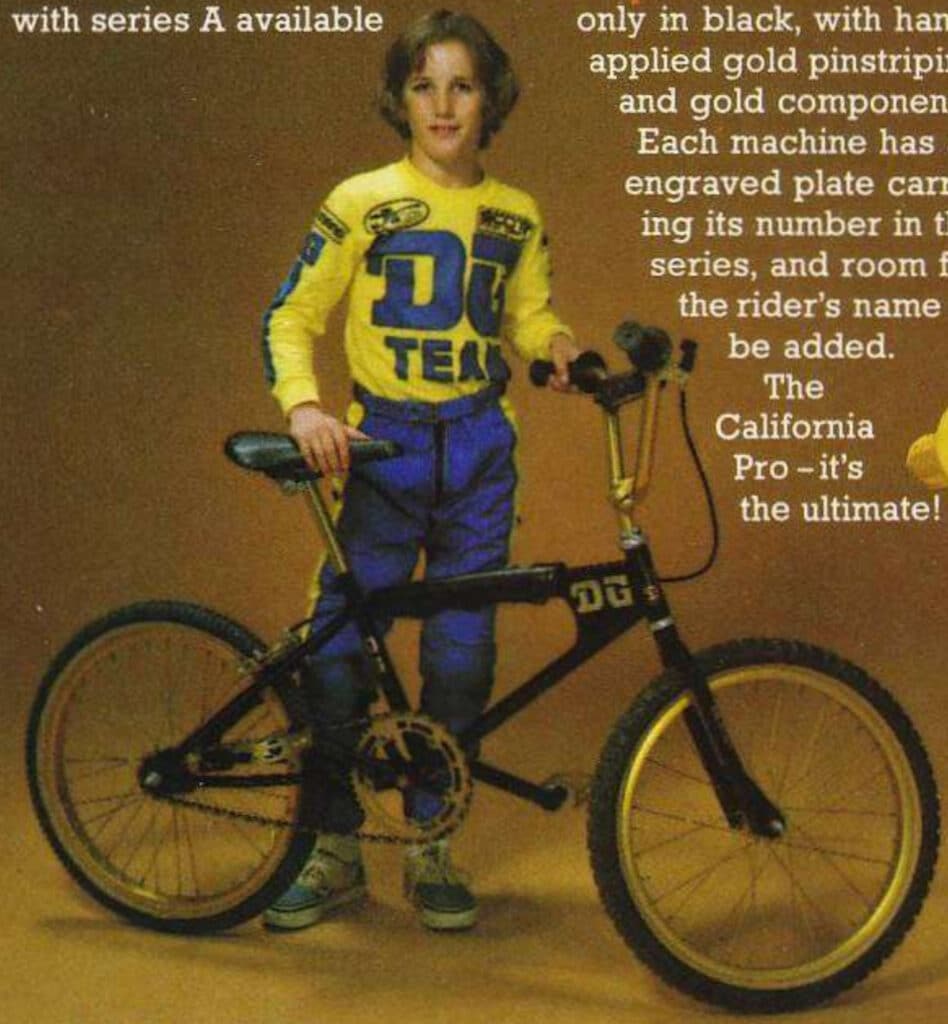

Kyle Fleming was a thin, wiry, thoughtful kid who didn’t like too much attention. Once, his dad, Carl, pulled up in front of school towing their Pro-Trac trailer with various racing decals and “Kyle Fleming” plastered on the sides; they were heading to a race. Kyle told his dad how much that embarrassed him. He wasn’t too shy about winning, however, and he did a lot of that as a national BMX champion.

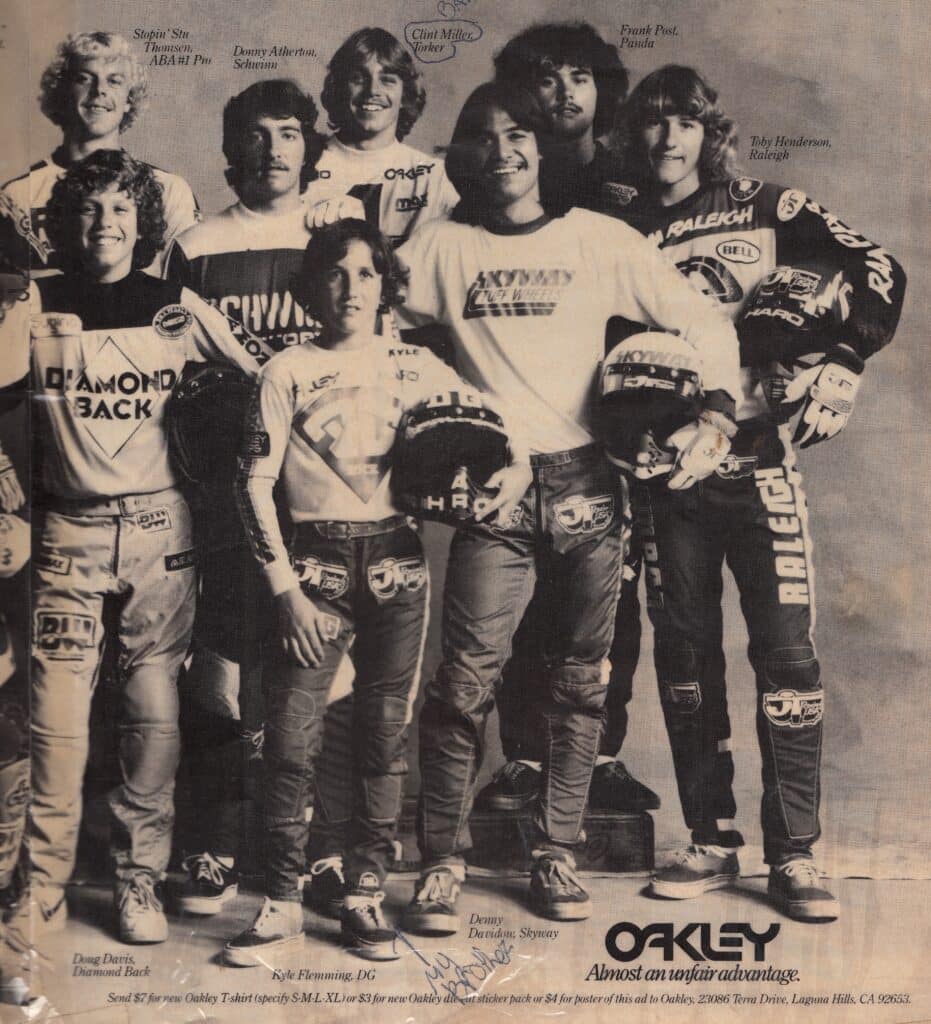

At nine years old, he was the American Bicycle Association’s national number one amateur rider. He traveled to California, New York, Florida, Texas and Washington to race. He was in Oakley advertisements, sponsored by DG with his own signature frame and, in the summer of 1979, became the youngest rider to be interviewed for BMX Action magazine. In 1992, he was posthumously inducted into the American Bicycle Association Hall of Fame.

“When I go out there I want to win. I mean, I know I’m gonna win,” he told BMX Action. “You don’t go out there and say ‘I don’t know…this kid might beat me….’ You just go out there and say, ‘I’m gonna win.’”

But he was humble, and almost philanthropic. When other kids approached him for his autograph after races, he’d sign his trophy and hand it to them. At his kitchen table in Phoenix, Arizona, he practiced his signature until it was perfectly legible.

Robert “Fig” Naughton remembers the first time he saw Kyle. They were in 5th grade. The Fleming family had moved to North Phoenix, and Kyle walked into class wearing a full DG-branded wardrobe: hat, shorts, shirt, socks. They quickly became friends, and Kyle thought “Naughton” sounded so close to “Newton” that “Fig” would be a good nickname. It stuck for life. The two raced around the neighborhoods in Kyle’s sidehack BMX rig, blasting into garbage cans and shopping carts. Naughton still has the bike today. It’s covered in dents from their adventures.

In 1980, at a BMX event in Amarillo, Texas, Fleming told his dad he didn’t want to race anymore. “When I knew his heart wasn’t in it, he wasn’t going to win anymore,” Carl Fleming said. Kyle didn’t ride his first motorcycle until he was almost 11. It was in the desert, and he rode a Yamaha YZ80 back and forth in a straight line between his parents while he learned the clutch and shifting.

People like Kyle who win at everything, they have that aura.

–Robert Naughton

He raced a few desert events and then, as in BMX, he escalated through the minicycle ranks in motocross – beginner, novice, intermediate – and at 12 years old, he raced expert in California’s Golden State Series. One of Kyle’s first races as a novice was at Saddleback, where he won the first moto by nearly 30 seconds and then broke his arm while goofing off between heats.

Carl remembers the motocross part of Kyle’s life as being a blur. He never went through an entire season before moving up to a more competitive class. But that was the family motto: To be the best, one must race with the best.

Kyle excelled at anything he tried. Carl enrolled him in Kenpo Karate to improve his reflexes and within four months, still a white belt, he earned two medals in a tournament. Even at the arcade nobody could match his Asteroids score. “Give him four quarters and he’d be there for four hours,” Naughton says. “It didn’t matter who he played; they lost. People like Kyle who win at everything, they have that aura. People knew they were going to get second when he showed up.”

By the summer of 1982, Kyle was a top-five rider in the 80cc expert classes and held one of the coveted spots on Team R&D Suzuki. He was only 13 and competing against riders two and three years older. At Ponca, which was then the biggest amateur national motocross race in the country, Kyle ran near the front in his qualifying heats but didn’t crack the top five in the finals. Still, it was a great weekend for the up-and-comer, and Carl popped his head into the motorhome after the race and flashed his son a thumbs up, which Kyle reciprocated.

A few minutes later, Kyle stepped out and said he was heading into town to have lunch with Dana Duke. “I said, ‘That’s fine, you have a great time,’” Carl said. “Oakley was his sponsor. He had been on Oakley since he raced BMX.” On August 2, they had planned to travel from Oklahoma to Tennessee for a new race billed as the AMA Kawasaki National Motocross Championships at Loretta Lynn’s.

Rick

There’s a home on 42nd Street in Quartz Hill, California – a 3.7 square mile community west of Lancaster – where 200 trophies lie buried in a backyard. When John Hemme Sr. sold his family’s home in 1988, he didn’t want to keep the trophies, but he also didn’t want to see them tossed in a dumpster. So, just as he had done with his son six years earlier, he buried them.

Rick Hemme was the middle child of John and Vivian. He was quiet, and if he didn’t already know you, he didn’t say much – if anything at all. As he grew into his teenage years, he didn’t show much interest in chasing girls or attending social functions with his classmates. Still, he was likeable. “There isn’t one person on the face of this earth that didn’t like him,” said his brother John. “He just wanted to ride his motorcycle.”

He started with an Italjet at four years old. John Jr., two years older, was scared of motorcycles at first and Rick got a few weeks of riding in before big brother. They chased jackrabbits in the desert and raced motocross at Edwards Air Force Base, which is where they saw their first race with their Uncle Jack. Rick’s first big event was in 1975 at the World Mini Grand Prix; he won the beginner class.

Three years later he won five classes at Ponca City – 9 moto wins and a third. His dream was to become just like another great motocross champion to emerge from Quartz Hill: three-time AMA Supercross champion Bob Hannah. When he earned sponsorship from R&D Suzuki, his name and photo appeared in full-page Cycle News win ads and even in a Suzuki promotional video where he plays a daydreaming pupil.

In 1982, at 16, he was one of the best minicycle racers in the country and traded wins at the major races with names like Bruce Bunch, Paul Denis, Larry Brooks, Mike Healey and others. At Ponca in 1982, Hemme finished second in the 83 stock and fifth in the modified, classes and he won the Super-Mini 105 division. His final moto was in the 105 class, and John Sr. remembers Rick winning by half a track.

Rick was small, barely 105 pounds but, like Bruce, he planned to turn pro. John Jr. remembers negotiations going on with Honda for $40,000 a year. John Sr. remembers talking to representatives at Yamaha. In August of 1982, however, Rick focused on acquiring a new Toyota pickup truck, just like Bruce’s, and he and his brother arranged to buy one from an Oklahoma dealership and drive it home to Quartz Hill, where Rick would begin his junior year of high school.

When the racing at Ponca concluded, the senior Hemme and his oldest son loaded up the bikes. He asked Jr. to go find Rick so he could help, too. Senior remembers Rick showing up with Kyle and Bruce and asking, “Can I go with them and Dana [Duke]? He wants to buy us a hamburger.”

“I don’t want you to go,” his father said. “I want you to help.” Rick pleaded, and he finally relented. After all, he thought, the kid had just ridden his heart out and won a national championship.

The Duke

In 2000 or 2001 – he can’t exactly remember – Dana Duke walked around Long Beach, California with three roller bags containing all his belongings. He was broke. BMX Freestyle legend RL Osborn picked him up. He fed and housed Duke and Duke repaid Osborn by giving him a hand with his carpet cleaning business. In the garage Duke found a weight bench with a 45-lb. bar on the hooks.

He weighed 152 pounds but felt broken down from years of surgeries and complications. He lay on the bench and tried to unrack the bar. He could only lift one side, and he broke down in tears in front of Osborn, who refrained from coddling him. Instead, he told Duke to never give up.

At 3 o’clock every morning, Duke went back to the garage to work out before the carpet care crew started its shift. In 2006, Duke won an English body-building championship in the 50+ division. He weighed 215 pounds at the height of his competitive career and could press 315 pounds on the bench.

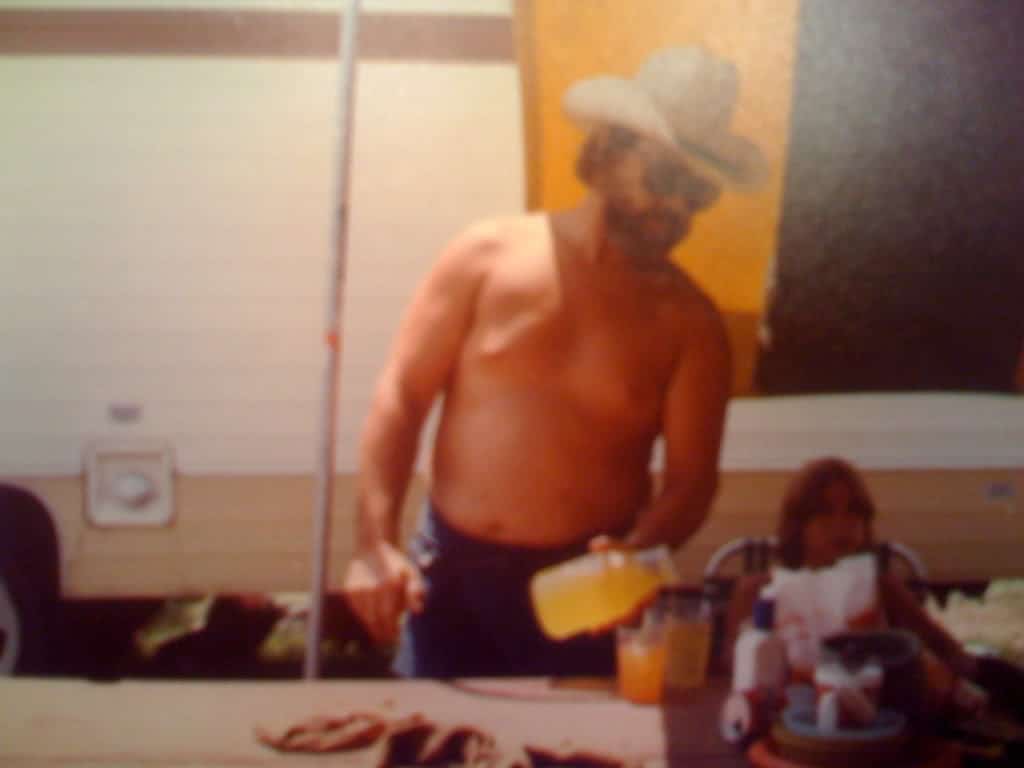

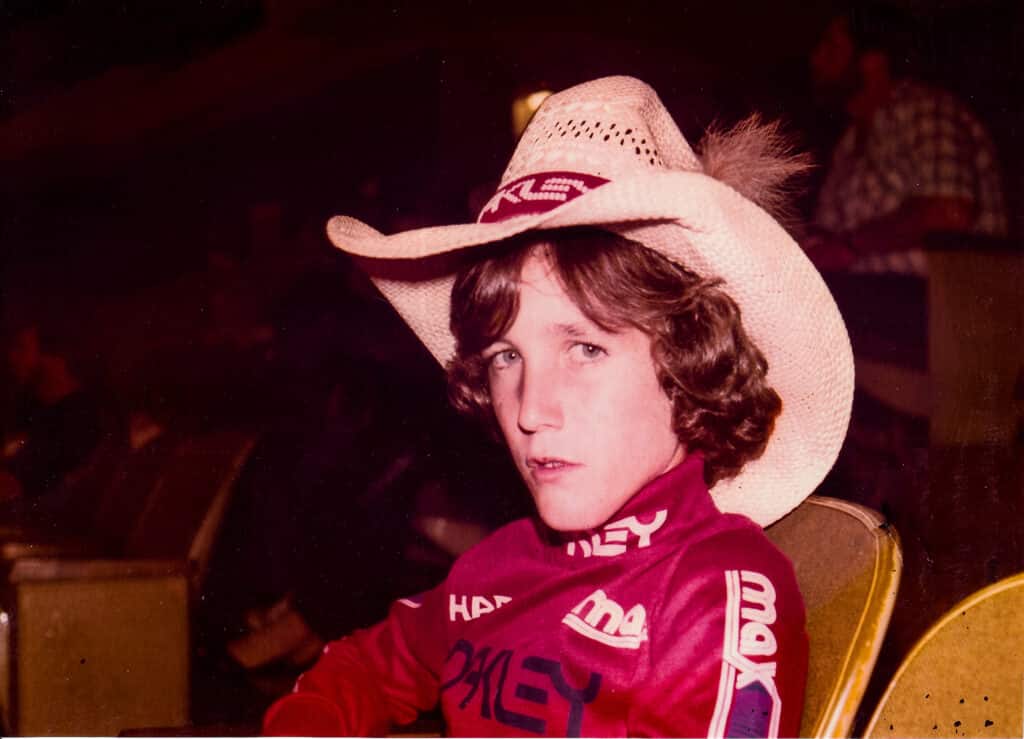

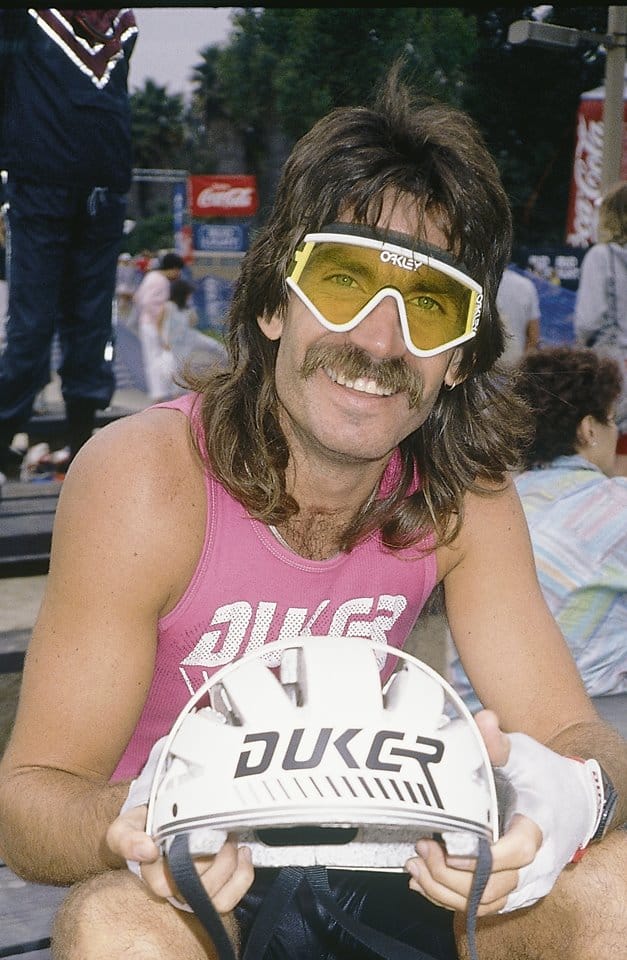

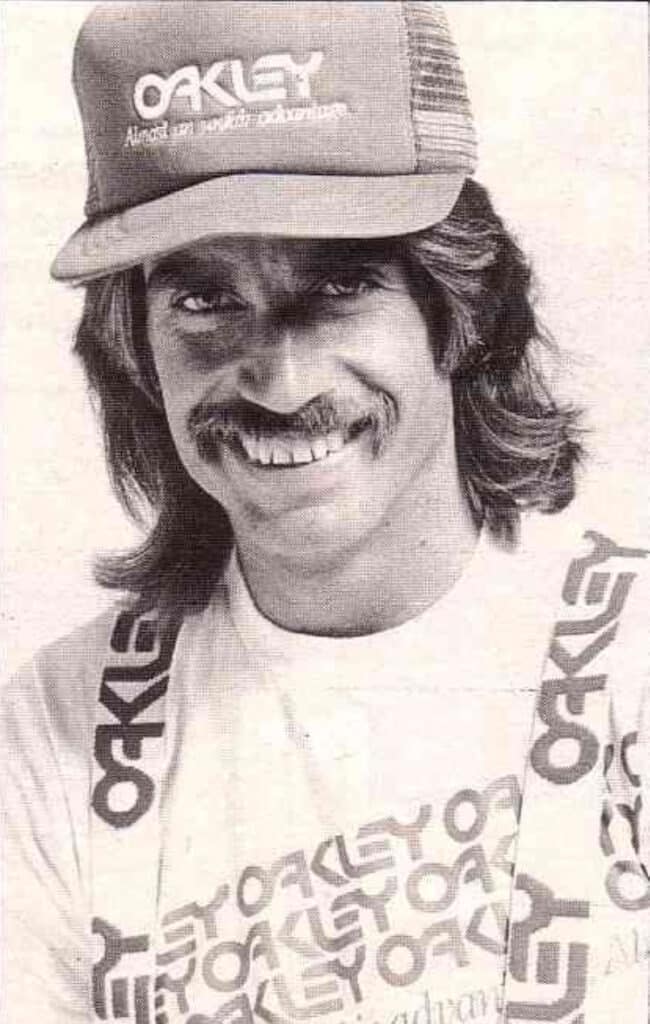

Duke was once the third employee hired at Oakley, in what now seems like a different life. A sports marketing representative, he signed BMX and motocross racers and made sure they were taken care of at events. And he did it with a proprietary blend of energy, charisma and flair.

Duke grew up in Pasadena, California. Raised Mormon, he wasn’t very active in his church as an adult but he followed the basic principles and didn’t drink or smoke. He loved motorcycles and first raced a Hodaka 100. He watched the Friday night races at Irwindale Speedway and particularly enjoyed the way the sport brought families together. He also loved playing basketball; he was in a church league. That’s where he met a man named Jim Jannard, who in 1975 started a little company called Oakley out of his Pasadena garage.

Duke was in his mid-20s in the late ’70s and started hanging around. “He really fell into what he was meant to do,” Jannard said. Literally. Duke often painted houses to make ends meet, and during a job at the Jannard home, he fell through a window into the room where Jannard’s daughter slept in a crib.

I really didn’t know what he was going to do for us.

–Jim Jannard

Duke wanted to help with anything. “I really didn’t know what he was going to do for us,” Jannard said. “I couldn’t keep him away if I wanted to.” Duke wore him down, and Jannard took him to a BMX race in Amarillo, Texas, where he was recruiting riders to run the handlebar grips he invented. Within minutes, Duke disappeared, and Jannard later spotted him effortlessly chatting up crowds. “Everyone seemed to love him and embrace his unusual personality. That’s when I knew he was going to be an asset to the company. He ended up being so likable that he shouldered the sports marketing duties.”

To the BMX and motocross industry he became known as “Duker” or “The Duke.” With his Oakley-emblazoned cowboy hat and goggle-strap-suspenders, tube socks and too-short shorts, he was almost a caricature. Duke laughs today and says he simply didn’t want anyone to miss him. His abilities, however, silenced doubts about his gimmicky appearance. BMX bench racers still talk about how Duke could slice and swap a set of grips faster than one could say “wheelie.”

Ricky Johnson was the first motocross rider Duke signed, and RJ fondly remembers always being “stoked out” with product. The Duke walked along the starting line with bags of labeled goggles and different lens options, all packed with tear-offs. “I wanted to make the riders feel like they were part of a real professional sport,” Duke says. “It added to that glory. I just look at it as, I’m going into warfare, nobody knows who I am, but how can I get the best riders in the world in my goggles?”

In Duke’s Oakley contracts, the last line read that the rider had to be his friend for life. Duke was all business, but he liked to keep it fun. “I could see why Jim hired him,” Johnny O’Mara says. “Jim was ultra-picky on who represented his company. So many people wanted to hang out with you. I never had that feeling at all with [Duke]. I had total trust in him.”

Oakley prospered and its Factory Pilot products were highly desired, especially since riders like Johnson, O’Mara, Mark Barnett and Jeff Ward all wore them. R&D Suzuki’s Kyle Fleming and Larry Brooks had long been with Oakley. Brooks grew up near Jannard and Duke, and he remembers first meeting them at a riding area called Hobo Junction. By the time Brooks turned 13, he was also one of the top minicycle racers in the country.

In late July 1982, The Duke headed to Ponca City to take care of his riders and try to persuade two more big names to join the Oakley family: Bruce Bunch and Rick Hemme. After being shooed away from the R&D pits several times by Rudy and Dean Dickinson, Duke took Bunch, Hemme and Fleming into downtown Ponca to the Sonic Burger on 14th Street for a post-race victory meal and to persuade them to switch from Scott USA to Oakley.

August 1, 1982

Bruce Bunch sat in Rick Hemme’s motorhome eating Apple Jacks with Rick and his buddy Chris Taylor. He mentioned that he wanted to go back to his room at the Holiday Inn and get cleaned up. It was mid-afternoon, the racing was over, and the long weekend hadn’t been the minicycle sendoff he’d hoped for. His best overall finish in the three divisions was a third. He rode the entire event with the cast on his left wrist.

Outside the motorhome, Bruce, Rick and Larry Brooks connected with The Duke, and the three piled into his car – Bruce in the passenger seat, Rick behind the driver and Brooks behind Bruce. They made the long drive from the back of the property down the gravel road that circumnavigated the course to the front gate, but first stopped to check in with their parents.

Ralph Bunch recalls Bruce telling him that Dana wanted to buy them a Coke, and Ralph said that was fine but to just stay at the hotel when they were done. The Sonic was just a few blocks from the Holiday Inn (now a La Quinta Inn), which was less than two miles from the track.

When Ralph Brooks (Larry’s father) saw his son, he reminded him that local radio station KLOR wanted to interview him and he needed to get that done first. He told his friends to go ahead but to pick him up a burger, fries and shake. The number of people who claim they almost got in – or were asked to get in – Dana Duke’s car that afternoon far exceeds the actual capacity of the vehicle, but when Brooks got out, Kyle Fleming definitely got in, and they left. Nobody remembers an exact time of departure, but it was afternoon, the racing finished, and families were loading up and leaving.

Chris Taylor was 17 at the time, and remembers he and his father, Dave, loitering for about an hour. The Bunch and Taylor clans often caravanned together and convened at their Lake Havasu-area vacation home. Dave motioned for Chris to jump in the truck; it was time to go. They drove east down Prospect Avenue and crossed the railroad tracks that the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company used several times a day. It was a bumpy, pothole-filled two-lane road, and the railroad tracks did not have automatic arms that fell when trains came through. The 10 other crossings within Ponca City limits did in 1982.

The crossing had a raised hump, and locals claim cars often jumped the tracks. The surrounding landscape is flat but for westbound motorists, the view of the southbound trains was (and still is) partially obscured by several long outbuildings from a lumber yard. Trains used to come through at speeds of 50-60 mph.

According to a 1984 deposition involving Lee Knight, Ponca’s director of traffic engineering at the time, the city’s 10 other crossings had automatic gates because they were dual-line tracks. The crossing at Prospect was a single-line track and had only side-mounted flashing lights on either side of the road.

In November 1984, overhead cantilever-style lights were installed, but it wasn’t until November 20, 1989 – one month following another fatality – that automatic gates were finally implemented at a cost of $105,600. The project had already been scheduled, and the fall 1989 accident was just a cruel coincidence.

The Taylors turned left into a gas station at the corner of Prospect Avenue and 14th Street. After refueling, they exited the opposite side of the station and turned right on 14th to head south toward Oklahoma City, where they could pick up Interstate 40.

Sitting at the light, they both noticed a lurching car opposite them. Its front end hopped up and down like the driver was rapidly alternating between the accelerator and the brake. It was Bruce, The Duke and the others trying to get their attention. When the light turned green, Chris remembers the car coming straight at them before turning left hard enough for the tires to squeal. Chris saw Bruce hanging out the front passenger window almost like he was trying to sit on the door frame. Chris could swear that he heard his friend yell, “See you at the river!” as the car careened around the corner and drove in the direction of the racetrack.

“Fucking idiots,” Chris remembers his late father muttering.

The car headed west into the searing afternoon sun and toward the railroad tracks, which were only a half-mile away. Chris saw his best friend alive less than 60 seconds before he was killed, but didn’t find out about the accident until the following evening. The Taylors drove for 25 straight hours back to Orange, California.

Mass Protest

Dean Dickinson liked to park the R&D Suzuki rig as far away from the front gate as he could get when racing at Ponca City. It was quieter there, and their backs were against an empty field. On the afternoon of August 1, 1982, he had a particular desire to escape chaos. A minor war had broken out between Kawasaki and Suzuki. Kawasaki Team Green’s manager, Dave Jordan, had made a pre-race decision to protest the stock class motorcycles of Bruce Bunch, Rick Hemme and Larry Brooks.

Immediately after the first heat race, the Suzukis were impounded, where they remained for the entire four days; they could be maintained only under the supervision of Kawasaki’s technician, Harry Klemm, who sat in a lawn chair and watched when R&D was allowed to work on their bikes. “Kawasaki felt there was adequate evidence that the stock [Suzukis] weren’t stock,” says Bob Brown, who was Team Green’s racing coordinator at the time. The protest wasn’t his decision, nor did he feel it was necessary, since Bunch and Hemme were simply better riders that season. He carried out his responsibilities, though, and defends the protests as legal, official and long-planned.

Kawasaki felt there was adequate evidence that the stock [Suzukis] weren’t stock.

–Bob Brown

Dean remembers Brown telling him the protests were “the best strategic move we ever made,” because it “messed with the kids’ heads.” Brown doesn’t remember saying that, but if he did it certainly wasn’t any kind of threat. Psychologically, Dickinson said, it would have been tough for a teenager to watch his bike get confiscated after racing it.

Glenn Dickinson was 16 at the time and can’t remember ever seeing his father, Rudy, so mad. Rudy called Suzuki’s racing manager, Tosh Koyama, who instructed them to protest every stock Kawasaki that crossed the line. Cost wasn’t an issue. The Dickinsons showed up after the championship-deciding heat with a stack of papers and a checkbook and pulled in every single Kawasaki.

“We wanted to give them a taste of what they were doing to us,” Dean says. “We were going to protest everything we could check. They’re not going to make Loretta Lynn’s, because we’ll have them out here for a week checking everything.” Kawasaki was the title sponsor of the inaugural AMA National Motocross Championships at Loretta Lynn’s, and Dickinson knew Team Green would be trying to use those same bikes when the event began in only a couple of days, 650 miles away in Tennessee.

Klemm was flabbergasted when he realized it was about to be his job to tear down 10 or more Kawasaki KX80s. R&D wanted everything inspected, right down to the big end rod bearing, which meant splitting the cases of the engine. “I said, ‘This guy must be insane,’” Klemm remembers thinking about Rudy Dickinson’s motives. “We would have to disassemble the motor down to the crank pin. He was doing it to be spiteful.” Jordan told Klemm to get to work, because he was eager to prove that Team Green did not cheat, and he ordered all remaining parents to get their race bikes into the impound area.

This guy must be insane.

–Harry Klemm

“I can’t believe this is going to happen,” Klemm says he said to himself. It was 95 degrees by 4 p.m., with a heat index even higher, and Klemm was hot, tired and hungry. Before he got started he snapped a few pictures of what the impound area looked like. A row of Kawasaki KX80s leaned against a bank of metal 55-gallon oil drums. In the distance, separated from the green machines, the three Suzuki RM80s sat in a neat, tight row on center stands.

At some point during the protest, Dean Dickinson escaped to the R&D box van to clean and loading up for the drive back to Norwalk, Calif. It was peaceful at the truck, and Dickinson remembers hearing what sounded like a scene from a black-and-white gangster movie – the squealing of tires around a corner and then metal smashing and crunching. He shrugged it off and went back to loading up.

People who attempted to leave the racetrack after 4:43 p.m. to drive into Ponca City were unable to cross the railroad tracks that intersected Prospect Avenue, only a mile from the front entrance of the venue. Glenn Dickinson was one of those affected drivers. He had taken Rick’s mom and sister, Vivian and Cheryl Hemme, to the Holiday Inn so they could get ready for the awards ceremony. He hit a detour on his way back to the track. Meanwhile, John Hemme Sr. and Jr. left together in the family motorhome after 4:43 p.m., but before news and details of the accident had reached the track. They both recall a funny feeling as they took the detour.

About 10 minutes after he snapped his photos, Klemm returned to the impound area with his tool bag to begin the teardowns. That’s when Rudy Dickinson walked up and leaned against a fence post. “So, are we going to tear down these motorcycles?” Klemm asked him. Dickinson was sobbing heavily. The only distinct sentence Klemm could make out was, “Harry, I can’t believe what’s happened. I’ve been such a fool.” Klemm thought they were about to have a “powwow” about the protests, but Dickinson’s emotions were in a shambles.

“He said something about a crash,” Klemm recalls. “I thought he was talking about a motorcycle racing crash. He was so broken up.”

Back at the hotel, John Jr. prepared to get in the shower while John Sr. wondered why his younger son wasn’t at the hotel. He couldn’t shake that “funny feeling” he had in his gut. He went down to the lobby, where he learned that there was indeed an accident at the train tracks. Nobody had details, so he left the hotel to go back to the track to see if Rick had gone there instead.

After Larry Brooks finished his radio interview, he wandered around, threw some rocks in a pond and then waited with his dad for the outcome of the protests. Sitting with his father, Brooks remembers the atmosphere turning to confusion and disbelief. Vehicles came back in the gate and police officers exited squad cars. Larry spotted his mother.

“Dude, it was just mayhem from there on out,” Brooks says. Larry’s mother, Jackie, squeezed him like a stress ball. The last time she had seen her son, he was driving away in Dana Duke’s car. When someone came to her room at the Holiday Inn to inform her of the accident and that kids were dead, she grabbed her sister and raced to the train tracks.

There were only two bodies; one had a cast on its left arm and the other had braces. Neither was Larry, and so Jackie went to the track. In an attempt to filter how the news reached her son, she put Larry into the back of one of the police cars. From that point on, the intensely bright afternoon went dark for young Brooks.

For at least 30 minutes, Carl Fleming (and others) had believed that a boy named Kyle Lewis, another minicycle racer a couple of years behind his own son, was dead. The only piece of information Carl had picked up was that “Kyle was dead.” The possibility that it was his own son went over his head, and he instantly grieved that young Lewis – who would go on to win a 125cc Supercross main event days after his 16th birthday five years later – was dead.

Someone walked up to Carl and, in a cavalier manner with no preamble, said, “Your son was in an accident and he’s dead.” Carl remembers his wife going completely berserk, and then the blackness hit him, as well.

Cycle News reporter Karel Kramer saw a man run up to Team Green officials and yell, “You Kawasaki guys killed my son!” He also vividly recalls one woman’s reaction. “It might have been one of the mothers,” Kramer said. “She threw her hands up in the air and started running with her hands straight up. I don’t know how she didn’t cartwheel.”

Dude, it was just mayhem from there on out.

–Larry Brooks

Ralph Bunch doesn’t remember his own outburst toward the Kawasaki officials, but several witnesses, including John Hemme Sr., recall the exact scene. “I could have been mad enough to do that,” Ralph said. “I can’t deny it.” He only remembers the shock of the policeman’s news and then stepping into someone’s motorhome.

Klemm was approached by race official Ted Morewood, who told him what had happened. Suddenly, he understood why Rudy Dickinson was so upset, but he still thought someone “had their wires crossed” and didn’t fully believe it. Nevertheless, the protests were called off. Team Green’s Bob Brown walked to the starting line and bawled for what seemed like an hour. There was a point in the confusion when he had thought his own son was in the car, too.

Oakley’s Jim Jannard Saves Dana Duke

Duke has no memory of August 1, 1982. He only knows what people have told him and what he’s been able to read from newspaper articles.

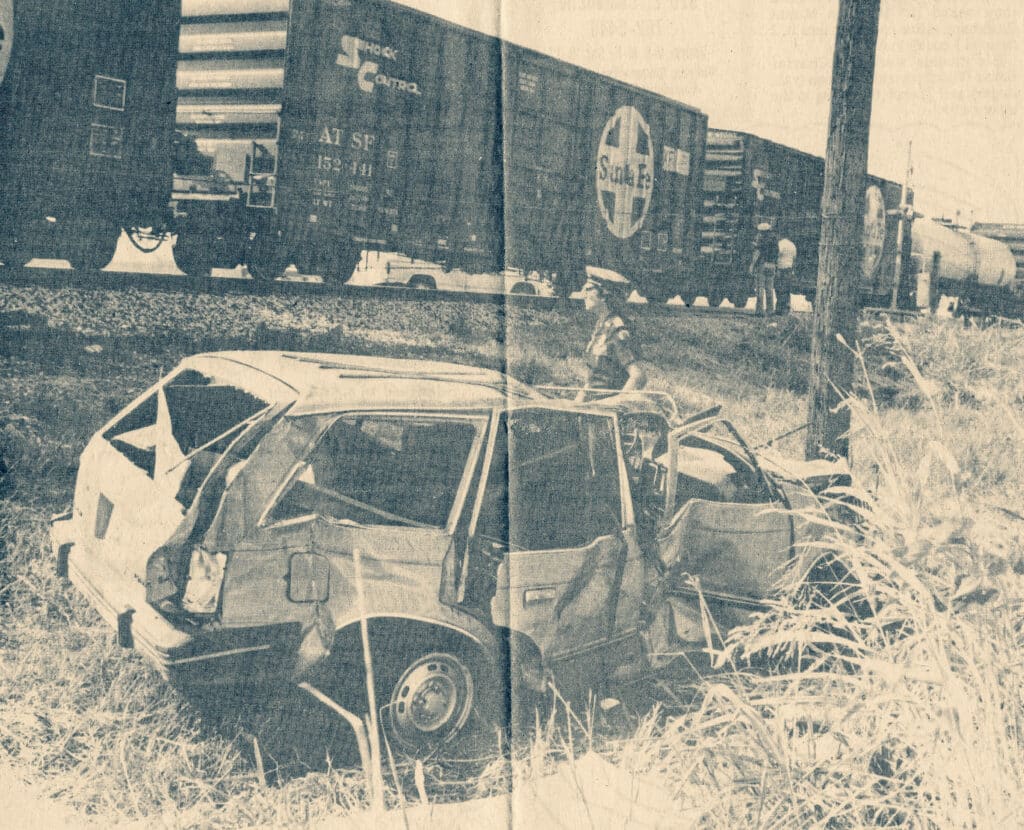

The report from the Ponca City News, which cited investigating officer Mike Shallop as its primary source, said Duke’s westbound vehicle skidded for 31.5 feet in the eastbound lane before striking Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company train number 3700.

The car was dragged 78 feet and finally came to a rest in the grassy ditch on the east side of the tracks. The windows were all blown out, and the point of impact was clearly visible on the passenger side. All four passengers had been ejected from the car. The lights were working during the time of the investigation, but the newspaper couldn’t confirm if they were flashing at the time of the accident.

“I remember their smiles, and that’s what hurts,” Duke says today. “Every day I try to understand what happened. I think of the accident every day when I get out of bed. Unfortunately, I survived. I’d trade places with those boys in a heartbeat.”

Rumors, blame and excuses from a grief-stricken motocross community have remained consistent over the decades and have spread online in forums and groups where memories of the boys are kept alive: The sun was in Duke’s eyes and he couldn’t see; he was trying to jump the tracks and didn’t realize there was a train coming until it was too late; he went around a line of cars that was already stopped because he thought he could beat the train; the windows were up, A/C on, radio blaring, and nobody was paying attention.

There are no witness statements, and the police reports were officially destroyed after 10 years. It’s simply impossible to know what really happened, or even why Bunch was in the car at all when his father had asked him to stay at the hotel.

The head trauma Duke suffered erased his memory. He can’t even remember what the Ponca City racetrack looked like. In addition to being in a coma for two months, he lost his spleen, broke eight ribs, punctured and flattened his left lung, lacerated his liver and broke his jaw in 10 places. His right ankle was crushed, as well as the L3-5 segment in his spine. He can’t remember if his legs were broken, but he wasn’t able to walk for months.

Even after recovering as much as he could, he was unable to perform his normal duties and he was forced to give up his position with Oakley. He battles neuropathy in his legs and walks with a cane. In 2017 he had three operations on his cervical spine to alleviate the narrowing of his spinal cord and prevent paralysis.

Ultimately, he credits Jannard for his survival. Jannard, the billionaire founder of Oakley and later, RED Digital Cinema cameras, has always been a staunchly private man. According to a 1997 LA Times feature, “He has turned down all interviews, publicizing Oakley’s breakthroughs only in press releases. The company has never released a photograph of him.”

The scars haven’t gone away. They’re permanent..

–Jim Jannard

When asked to speak about the events surrounding August 1, 1982, however, he was quick to respond. “It was dark, dark days around the O for a long time,” he said in one of several phone calls. “The scars haven’t gone away. They’re permanent. It was as horrific as anything you could possibly imagine. Kids lost their lives, and Duke’s life was ruined. Everybody lost on this thing.”

When Jannard found out about the accident, he flew to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Duke was hospitalized. “It didn’t look like he was going to make it,” Jannard says of Duke’s condition. After visiting with Duke he drove to the Ponca City crash site 90 minutes away and made it a point to experience the intersection both in a car and on foot at 4:43 p.m., the exact time of day of the accident. He was shocked by what he saw.

“You could see it wasn’t safe,” he said. “Being there, it’s a way different picture than what people imagine. There was just no warning. I stood right in the place, where I would call it judgment time, and I couldn’t see the [warning] light,” Jannard said. “You didn’t have to be going Mach 8 to run out of room.” The skid marks that went into the eastbound lane were still there, and their arcing path indicated Duke’s car was parallel to the train when it collided.

“Honestly, I think they were wound up and [Duke] just wasn’t paying attention,” said John Hemme Sr. “That light, when it was flashing, you couldn’t really see it. You had to look hard at it.”

When Duke was able to leave Tulsa, Jannard rented a plane to transport him to Irvine, California, where he remained in a partial coma. He lived with the Jannard family for six months while recovering. “Had Jim not been there for me, you wouldn’t be talking to me,” Duke said. Duke says he hasn’t spoken about the accident in over 20 years, but he does remember calling each of the parents to apologize. He says Ralph Bunch was angry and hung up on him. None of the parents recall being contacted at all. Today, Hemme Sr. is as angry at himself for letting Rick get in the car as he is for any possible lack of responsibility the driver may have had.

The Painful Aftermath

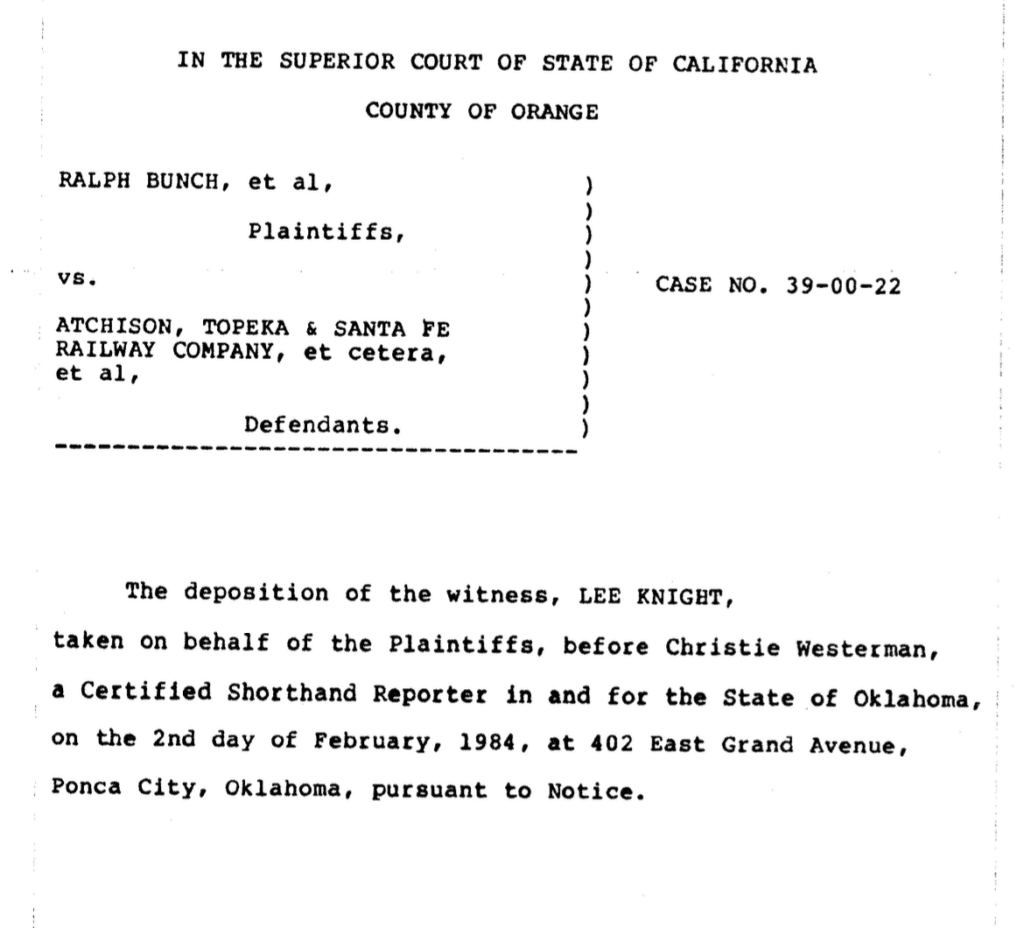

On November 5, 1982, Ralph Bunch, John Hemme and their spouses became plaintiffs in a lawsuit in the Superior Court of the State of California, County of Orange. According to court records, the complaint for damages was wrongful death, and the five defendants were Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company, Santa Fe Industries (the parent company of the railway company), Oakley Inc., Dana S. Duke and Hertz Corporation (rental car).

The four causes of action were negligence against the railway company and its parent company; “failure to warn” against the railway company and its parent; negligence against Hertz, Oakley and Dana Duke; and a survival action – legal recourse that allows the estate to be awarded damages the deceased might have been able to recover had they not died – against all five defendants.

General and special damages were sought, as well as $30,000 for medical costs and, for the survival action, the plaintiffs asked for $2,000,000 in punitive damages.

Carl Fleming didn’t even know the lawsuit was happening. He remembers getting a phone call informing him to get his own lawyer. Hertz Corporation responded first, with an objection to the fourth cause of action. In February 1983, the railway company filed a denial, as did Oakley.

On April 28, lawyers representing Hertz, Oakley and Duke demanded a jury trial. Nearly two years and nine different filings later, Ralph Bunch filed a notice of waiver of jury trial. The final entry on the case summary was “Notice-other (notice of undocumented action-other) was filed by Hertz Corporation” on March 13, 1985. According to the courthouse, no documents were entered. Fleming, Bunch and John Hemme Sr. all confirmed that the case settled out of court.

“Ralph and I settled for $1 million from the rental car place (Hertz),” Hemme Sr., said. “That’s the way I understood it; the rental car policy paid for it.” Repeated requests to speak with Hertz representatives were not returned.

John Hemme Jr. saw Duke at a Supercross race at some point in the 1980s but didn’t approach him.. “I want Dana to know that I have no bad feelings about it,” Hemme Jr. said. “It was an accident that happened.” Larry Brooks went to see Duke in the hospital when he emerged from the coma. It was emotionally draining for a 13-year-old who had recently watched three of his friends get buried, one of them – Rick Hemme – in his riding gear.

Brooks cried for a week straight after the accident and contemplated quitting racing altogether. He went on to a successful 12-year professional career, the later won five Supercross championships as a team manager with Jeremy McGrath, Chad Reed and James Stewart.

Dana’s memory loss bothered Brooks. “I was really young, and I couldn’t understand why he couldn’t remember something that was so important,” Brooks said. “I just didn’t get it. I couldn’t be around this. I needed some support.”

What Might Have Been?

Even though he hates to say it, Robert “Fig” Naughton’s professional racing career took off because of Kyle Fleming’s death. Naughton’s parents were divorced, and he only rode for fun until Kyle’s dad Carl started taking him to races. After a couple of years, it became emotionally difficult for the Flemings and they backed away. “Carl knew how to set up equipment, and he knew how to give a kid confidence,” Naughton said. “I still admire Carl and Paula. They’re good people.”

In 1986 Fig coincidentally earned national number 54, which was based solely on the total points he scored through the season. That had been Fleming’s racing number in 1982. In 1987, he missed winning the 125cc West Supercross championship by seven points, but earned 54 again. “What are the odds?” Naughton said. When he received his first mobile phone number, the last four digits he was given were 5544.

Those who raced against these young men, who watched them, admired them or raised them, continue to swap stories, share photos and keep the memories alive. Some who were asked to get in Duke’s car openly say they wish they had. Maybe that slight delay of adding one more person would have been enough to put them on a different course with time, preventing the accident entirely. Some can’t shake the anger that motocross fans were robbed on August 1, 1982. Robbed of what might have been, and left with an unfillable void.

Motocross didn’t die that hot day in middle America, but a piece of it did.

Please share this story with a friend and keep the memory of these boys going.