50 Years of Sundays: “On Any Sunday” Will Change Your Life

By

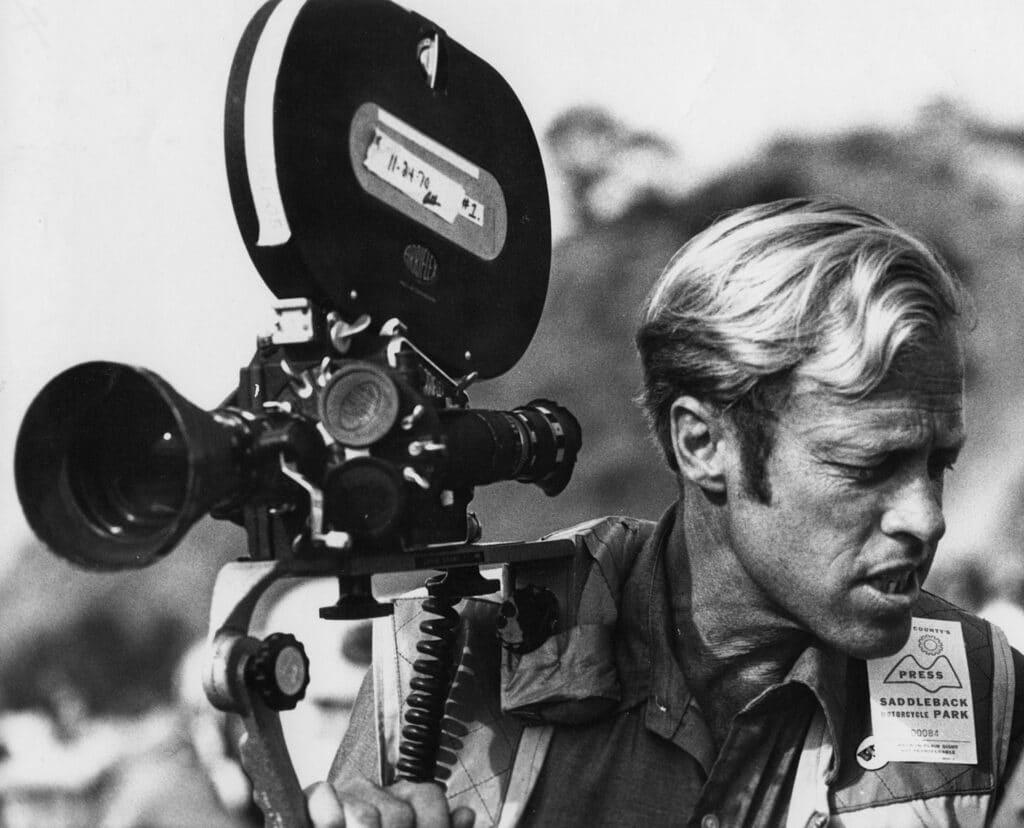

Five decades later, Bruce Brown’s 1971 motorcycle documentary continues to influence.

The Academy got it wrong. In the end, “On Any Sunday” won it all. And it’s still winning. Fifty years after its theatrical release Bruce Brown’s 1971 motorcycle documentary continues to defy time and technology.

If Oscars were handed out based on the potential of societal influence, the Academy may have handed the statue for Best Documentary Film to Brown instead of Walon Green, whose insect world film “The Hellstrom Chronicle” combined elements of science fiction and horror and, in the end, frightened people from weeding their own gardens.

On Any Sunday Merch

A masterpiece in cinematography, Hellstrom became a worthy teaching tool in high school science classes but didn’t create a surge in new entomologists and faded into obscurity over the decades. It has no official hard copy or streaming distribution but thanks to YouTube we can all experience how terrifying Venus flytraps are for small insects (seriously, it’s an edge-of-your-seat scene).

Few movies remain relevant after a half century but “On Any Sunday” continues to achieve something far more; it still changes lives. The teenagers who bought matinee tickets in the summer of 1971 but didn’t emerge from theaters until midnight were the first generation of souls captivated by the sights, sounds, and sensations of watching motorcycles in this film.

Tribute Movie Poster

They liked the movie so much that they hid in theater bathrooms or darted through the doors of a different flick to wait for the next showing of Brown’s motorcycle movie. If there wasn’t a seat, they found a wall to lean against or a step to perch on and took another lap in the worlds of Mert, Malcolm and McQueen.

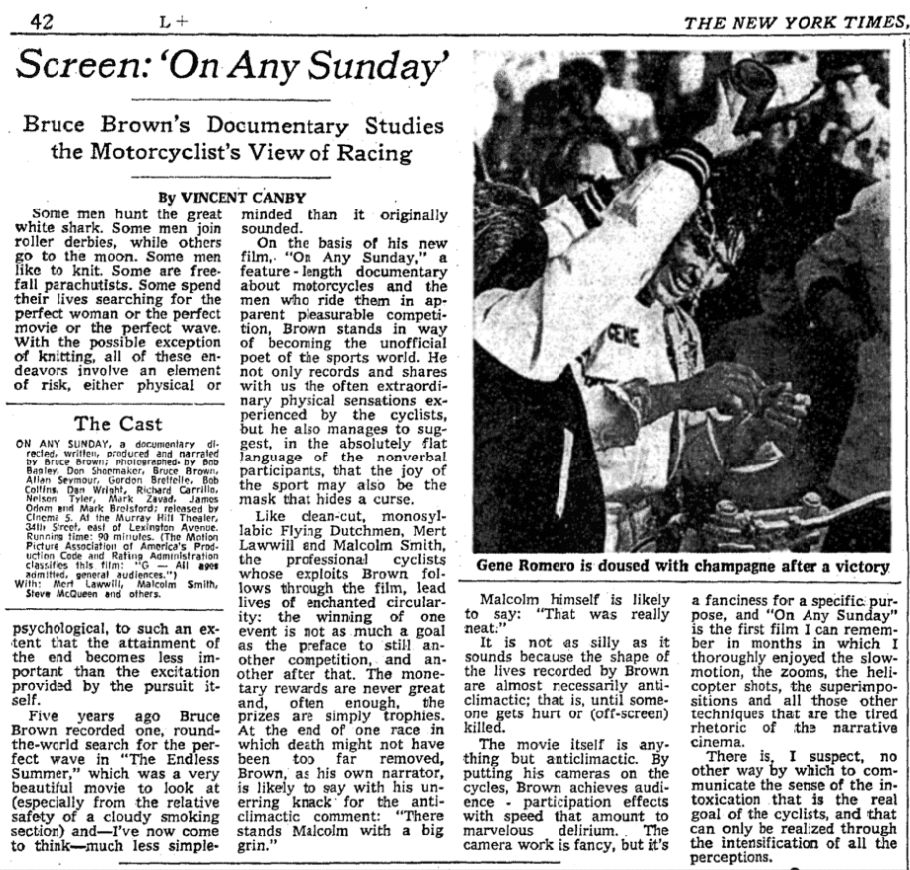

“New York Times” film critic Vincent Canby trashed “The Hellstrom Chronicle” one month before he saw “On Any Sunday,” which he enjoyed, it seems, much more than he expected to. “Brown stands in way of becoming the unofficial poet of the sports world,” Canby wrote on July 29, 1971. “By putting his cameras on the cycles, Brown achieves audience participation effects with speed that amount to marvelous delirium.”

Dan Geery bought into that delirium. Literally. His currency as a 13-year-old wasn’t the greenbacks he made pushing lawn mowers around Redwood City, California. It was a Honda CT70, for which he had to pay back his parents half the purchase price.

They didn’t like motorcycles, ’too dangerous, too fast’ but they were smart enough to use the little trail bike as leverage to encourage him to keep up his grades and as a tool to teach their son how to care for something and learn the basics of a trade.

On weekends, Geery’s dad loaded the CT70 into the back of the Plymouth station wagon and left him at the Foster City Salt Flats with a can of gas. Dan rode around on his own and watched the pros practice on the various sized flat tracks they built. Four to six hours later, his dad would pick him up.

Geery first heard about the movie from the hours he and his friends spent loitering around A&A Motors where they stretched the throttle and clutch cables of the Yamahas on the showroom floor and listened to professional flat track racers Jim Odom and Jim Rice tell stories from the pro circuit.

Dan can’t remember exactly who said it, but he has a vague memory of someone excitedly saying, “there’s a movie and we’re going to be in it!” When “On Any Sunday” opened at the Fox Theater in Redwood City, Dan lined up for the very first showing. Still ambivalent about dirt bikes, Mr. Geery went with his son to experience all the fuss.

“It enlightened him a little about why I loved bikes,” Dan says. “He really enjoyed it.” Yet he still wouldn’t let his son emulate Mert Lawwill and become a flat track racer, which was his dream. “He didn’t like those speeds,” Dan says of the line his father drew. Dan, 14 when first saw the movie, discovered motocross instead. At Christmas that same year, a yellow Yamaha MX90 leaned on a kickstand next to the tree.

“That I paid for,” Dan says, laughing. He spent the summer and fall mowing, raking and weeding for $1 an hour and made enough money to buy his own motocross bike, which he finally received on Christmas morning. Dan sunk himself deep into motocross.

He jokes that he didn’t even know his high school had a football team because he was so focused on racing. In 1975 he raced as a professional at the Hangtown Motocross National. In 2006, at almost 50 years old, he bought a steel shoe and finally raced flat track.

A few years later, Geery finally got the chance to tell Malcolm Smith that “On Any Sunday” changed his life. “I know he’s heard that a million times but he still had a smile on his face.”

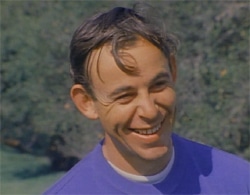

Malcolm Almost Said “No”

People like Dan Geery often wonder how life would have turned out had they not seen the movie. Malcolm Smith still wonders how much different his life would have been had he turned down the offer to appear in “On Any Sunday”. Which, he did. Sort of.

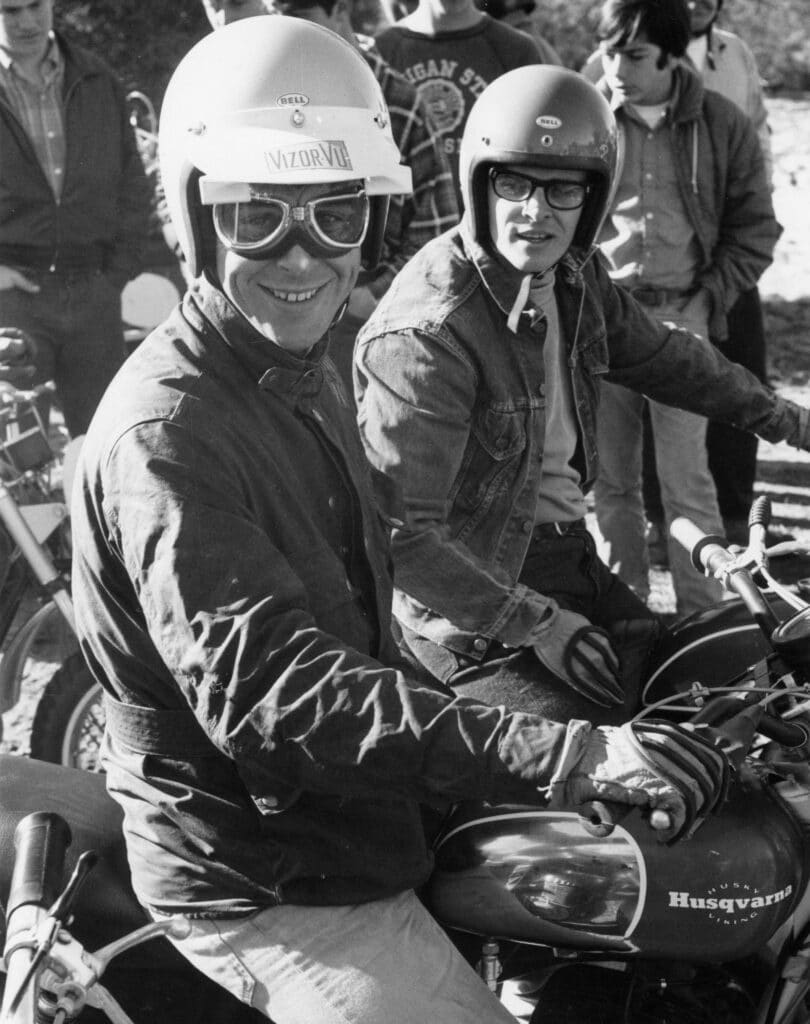

What he didn’t know at the time was that Bruce Brown hadn’t considered other options. Brown, who died on December 10, 2017, 10 days after his 80th birthday, used to joke that he only bought a Husqvarna because that’s what Malcolm rode.

With the same bike, he thought he might pick up the same skills. He soon realized it wasn’t about the bike. Brown liked how Malcolm could tear down a Husqvarna “in about 45 seconds” and he relied on Malcolm for all his mechanical work, too. So did an actor named Steve McQueen.

In the late 1960s, Malcolm owned the service department of Ken Johnson’s and Norm McDonald’s K&N Yamaha dealership in Riverside, Calif. In 1969, Ken and Norm wanted to focus on their growing air filter business (yup, that K&N) and Malcolm bought out the sales and parts departments for $125,000. Exact timing varies but Malcolm remembers that Bruce pitched a motorcycle movie concept to him before he assumed full ownership of the dealership.

Brown’s goal was to showcase motorcycling and motorcyclists in the same clean-cut, family-friendly way that his 1966 surf documentary “Endless Summer” did. Surfers were not all beach bums and motorcyclists were not Hell’s Angels or characters straight off the set of “The Wild One”. In Brown’s eyes, Malcolm Smith had talent and a persona as far removed from Johnny Strabler as he could find.

Months later, however, Malcolm felt swamped and overwhelmed with his new responsibilities at the dealership. He turned Brown down when the filmmaker called to schedule shoot dates. Undeterred, Brown said he’d check back in a few weeks. In a 2012 interview at his ranch north of Santa Barbara, Calif., when asked what plan B was, Brown said, “I never thought about it. I wanted Malcolm. And I always knew I was going to get Malcolm even if I had to cry. I really had no other options.”

Two weeks later, Malcolm said he felt better about his business and agreed to work on the movie. “That was the best decision I ever made,” Malcolm says. “Even if it hadn’t come out wonderful, I had such a great time filming and traveling together.”

When he first saw the movie a little over a year later, Malcolm was shocked at how much of the 90 minutes went to him and his adventures.

I thought it was going to be two to three minutes for me and gone. Bruce never hinted to me that I would be in it so much.

–Malcolm Smith after seeing “On Any Sunday” for the first time.

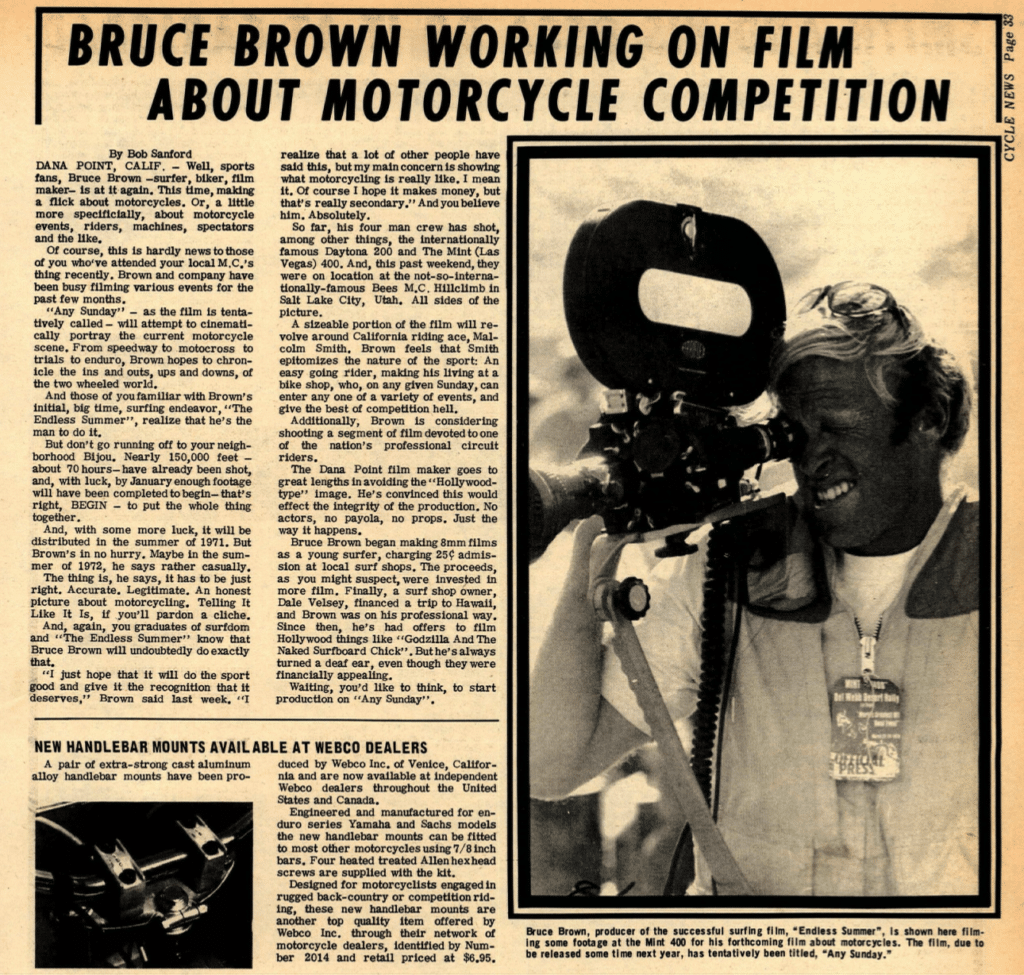

Maybe Malcolm missed the April 21, 1970 issue of “Cycle News” that probably sat on the counter of his dealership. In a half-page article, Bob Sanford broke the news that Brown would feature motorcycle racing in an already-underway documentary with the working title “Any Sunday.”

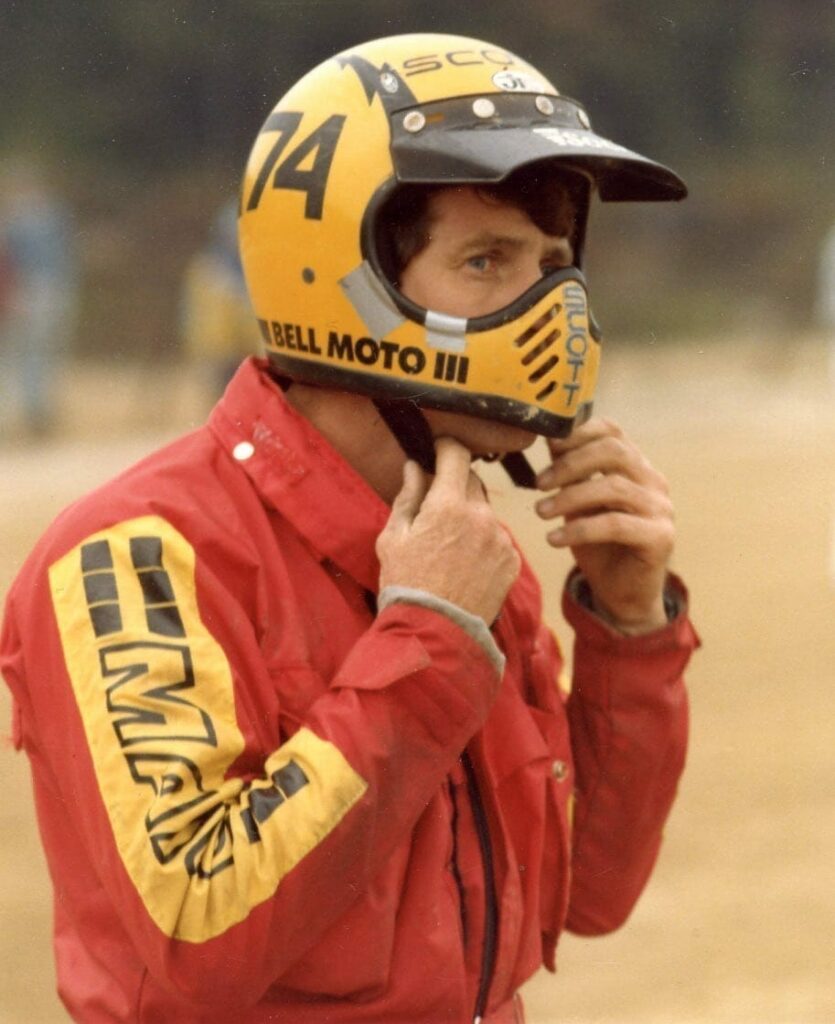

Next to a photo of Bruce peering through a viewfinder, Sanford wrote, “A sizeable [sic] portion of the film will revolve around California riding ace, Malcolm Smith. Brown feels that Smith epitomizes the nature of the sport: An easygoing rider, making his living at a bike shop, who, on any given Sunday, can enter any one of a variety of events and give the best of competition hell. Additionally, Brown is considering shooting a segment of film devoted to one of the nation’s professional circuit riders.”

The AMA Grand National series was five rounds deep by the time the announcement in Cycle News appeared. Before he knew which rider he would follow on the Grand National circuit (Mert Lawwill), Brown knew he wanted Malcolm as a centerpiece character in his film.

The triangle of talent was carefully selected to engage the moviegoers. You weren’t going to be Steve McQueen or Mert Lawwill, but Malcolm was somehow attainable, even if only in one’s mind. Lawwill represented the gladiator, the larger-than-life giant, even if he was only 5-ft. 6-in. tall. He was the AMA Grand National champion and on the quest for another title.

McQueen starred in blockbuster films but we connected with him because he liked to bang bars and get his fingers dirty along with every other weekend warrior. Still, he was Steve McQueen, one of the highest paid actors in the world.

But Malcolm Smith was everyone. Nobody deluded themselves into thinking they could beat Malcolm but they could certainly be him. He wasn’t an A-list celebrity or a Grand National Champion (although he briefly held a professional AMA dirt track license in 1959). Malcolm was the guy who made you feel like you could do it, too.

An Admission of Guilt

During a 2017 KTM executive dinner in Montreal, Steve Masterson found himself unable to contribute to the conversation, which is rare for the talkative and colorful Brit. He could no longer hide so he came clean and finally admitted something as egregious as not knowing what sports Tiger Woods or Michael Jordan are famous for playing.

He had never seen the movie “On Any Sunday”.

The men around him, including KTM North America’s President, John Hinz, stood abruptly, threw their hands in the air and shouted incredulously. Eyes bulged, the meal stopped. The group stared at Masterson. “They may have even questioned my intelligence,” Masterson says. “They freaked out.”

He likened it to trying to talk to someone who knows the lines from Monty Python or Star Wars as well as their own birth dates and Social Security Numbers. The passion was so strong and he couldn’t fake it anymore. But he knew it would catch him eventually. Feelings of being inauthentic had crept into Masterson’s mind.

As the president of Kiska North America, KTM’s design and branding agency, he’s a sought after speaker in the motorcycle industry, especially for the KTM dealer network who appreciate his sharp wit and stories. He’s been in and around KTM since 2004.

And his secret went deeper than just not seeing a movie. Steve didn’t ride motorcycles. At all. Never. “People just assume I ride because I work for KTM.”

Growing up in Reading, England in the 1970s, Masterson launched his bicycles off ramps but didn’t know anyone with a motorcycle. He’d never heard of English motocross icons Dave Bickers or Jeff Smith but he countlessly watched “Smoky and The Bandit” and “Cannonball Run” and idolized Burt Reynolds.

The Masterson house even had a 16-ft. tall CB radio antenna fixed to the roof while a Trans-AM and Ford Mustang sat in the garage. “We were living the American Dream inside a little house in England,” Masterson jokes.

By 2017, Masterson had lived in California for three years. He returned home from the Canadian trip on a Sunday evening. It was about 9:00 p.m. and his wife had gone to bed. He was tired, too, but knew he couldn’t walk into the office 12 hours later without arming himself with some “On Any Sunday” context.

Their reaction was so visceral. I think I would have been drawn and quartered had I not watched this movie.

–Steve Masterson on his KTM co-worker’s reaction to him not watching “On Any Sunday”.

Masterson pulled up the YouTube app and laughed at how grainy, pixelated and sepia-toned the pirated version looked on his 84-in. television. He leaned back in a recliner expecting a two-wheeled version of “Smoky and the Bandit.”

After ninety minutes he gently rocked in the chair with his arms crossed, deep in thought. He retraced every experience and every person he’d met through his work with KTM. Suddenly, he had perspective and even more reverence. “It’s not a prefrontal cortex (front of brain) film,” he says. “It appeals to the emotions. It’s like falling in love. It speaks to the heart.”

Despite working for a company that participated in every single motorcycle activity featured in the movie, it wasn’t until he saw it all on the screen, in one package, that it came together for him. The desert racing his colleagues occasionally talked about now seemed real. Before, he didn’t think those people actually existed.

Masterson’s career in the motorcycle industry shifted a gear. First, he earned his street bike endorsement. “That was the first time I realized that motorcycling can actually be dangerous!” Then he got on a KTM Freeride in a dirt parking lot and practiced figure eights. A few weeks later, a co-worker put him aboard a KTM 250SX-F and sent him out on the vet motocross track at Cahuilla Creek. He loved it but to this day he doesn’t let his wheels get off the ground.

In the spring of 2021 he finally bought his own motorcycle, a KTM Duke 390. Had he not seen the movie, who knows. “On Any Sunday” is like the first line of coke,” he says. “It’s free but you’re going to want more. The movie has taken me into many different areas but I still don’t know if I’m a rider. There’s still a few things I think I need to do, like run out gas in the middle of the desert.”

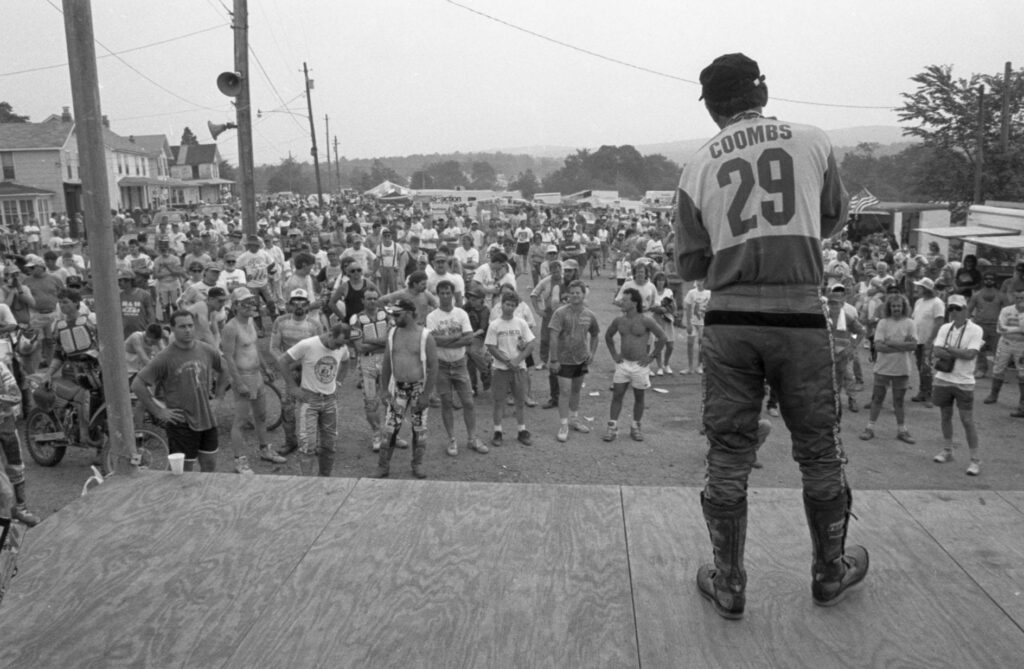

Birth of the Blackwater

The genesis of the grueling Blackwater 100 came when Dave Coombs Sr. watched a movie in a High Street theater in Morgantown, West Virginia. He saw Malcolm and 1499 other riders, including a man named Harvey Mushman, compete in the Elsinore GP, which started and ended on the streets of Lake Elsinore, Calif. A few years after seeing “On Any Sunday”, Coombs hosted his own event in the coal country town of Davis, WV. Like the Elsinore, the Blackwater 100 started and finished on the streets.

Rita Coombs won’t blame Malcolm but she knew her life was going to change before that movie had even ended. She could tell, just by the entranced look in her husband’s eyes that ideas were forming in his head. “I just remember sitting in the theater and thinking, ‘Oh, no. This is not good,’” she says.

Dave was a Morgantown-based musician and had recently bought a 1971 Triumph Bonneville to ride on the street with his bandmates. After watching “On Any Sunday” he went to a nearby motocross race and decided right then that he had a new hobby. According to his youngest child, Davey, his father walked over to the registration table and asked what kind of motorcycles they had on loan.

“Because nowhere in the movie did they explain that you had to bring your bike,” Davey says. “He was just going to sign up and grab a bike.” That week he traded in his Triumph for a Maico and went racing.

Rita’s intuition was right. Her life changed. She worked the scoring booths and registration tables at the local races. Dave quickly realized he was about a decade too late to start a professional motocross career and he became a promoter instead.

Dave died in 1998 but MX Sports, the promotions company he and Rita formed, now produces the Grand National Cross Country series (where the Blackwater 100 lived through 1993), the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championships at Loretta Lynn’s and the Lucas Oil Pro Motocross Championships among other events and properties.

The Modern Day Malcolm

Ryan Sipes still agonizes over Mert Lawwill’s loss at the 1970 Columbus, Ohio half mile. Lawwill dominated the race until the final moments when his throttle cable broke, “a $2 part”, as Bruce Brown bluntly stated in the narration.

Six weeks later a broken crankshaft causes a DNF on camera at Terre Haute, Indiana. Sipes wonders if the fraction of an ounce Mert shaved from that cam follower and all the metal ground off the gears could shoulder some blame for the rash of DNFs later that season.

Only someone who’s seen the movie 40 times could get this granular about the outcomes of races that happened 15 years before he was born. Sipes feels every loss because he’s been there. In 2014 he finished his professional motocross career and focused on new adventures in off road racing.

In 2015, at the 90th annual International Six Days Enduro in Slovakia, he did something no American had ever done: he won the individual overall. Malcolm Smith sent Sipes a hand-written note, congratulating him. Smith won 8 gold medals between 1966-1976, but never the individual award.

That winter, looking for enriching entertainment to watch while logging miles on his indoor spin bike, Sipes picked up a DVD copy of “On Any Sunday”, a movie he still hadn’t seen. It has become the soundtrack of his life. He plays it in his truck while he drives to races.

His son, Jack, watches it on road trips with dad. The scene where Jim Rice crashes in Sacramento mesmerizes him and he especially loves the trials riding and Widowmaker segments.

“I think I like it the more I watch it,” Sipes says. “I pick up more things each time.” Today, Sipes gets paid to keep the loosest and most diverse schedule of any dirt bike rider on the planet. He’s even won a few dirt track races. Since 2018 he’s competed in professional flat track, TT, hillclimbs, hard enduros, the ISDE, supercross, motocross and a variety of off-road events. He also squared off with freestyle motocross riders and learned a backflip in Travis Pastrana’s backyard.

He swears that the dozens of hours he’s spent watching and listening to “On Any Sunday” didn’t give him the idea to become General Sipes but deep down he knows it had some influence. Have fun on dirt bikes, don’t get too worked up about anything. That was Malcolm, right? Sipes takes pride when he hears people call him the ‘modern day Malcolm’. “It’s cool to hear that, but there will never be another Malcolm,” he says.

And if you’re ever at a go-kart facility and see the name Harvey Mushman in the lineup, check to see if Ryan Sipes is behind a steering wheel.

Discovering the Joy of Motorcycles

Joy Burgess was a 35-year-old widow and single mother who had never been around a motorcycle when she first saw “On Any Sunday” in 2015. She learned about the movie while reading “Malcolm! The Autobiography”, which a friend thought she’d enjoy, given her career as a writer and editor. She found the movie online and, to this day, can’t believe what happened next.

Her husband’s unexpected death a few months earlier destroyed her world but then a movie helped rebuild it. “It’s surprising how a single thing can change your life so drastically,” she says. “I felt like I had been introduced to something that had always been missing from my life.”

The diversity of riders in the opening segment hooked her and Bruce Brown’s story telling helped her believe she too could ride. She enjoyed watching the cheeky scene where the man teaches his neighbor and imagined herself in a similar situation.

The kind of person who enjoys the in-control feeling that comes from driving a manual transmission, Burgess likes working on machines; she paid close attention in the garage when her minister father worked on the family car. She found a used Honda XR80 with a finicky carburetor and taught herself to ride in the back yard of her central Florida home.

Now she goes trail riding to experience what she saw in the movie, particularly the closing scene where Mert, Malcolm and McQueen rip around the beach on the shore of the Pacific Ocean and Sally Stevens melodically sings “I’m flying…”. That scene, even from the grainy pirated version she found on the Internet, gave her goosebumps.

“The stresses in life can’t catch you when you’re in the wind. It’s nothing but you and the bike,” she says. “I saw freedom in that movie. I wanted the feeling more than anything.”

Burgess didn’t stop with learning to ride. She found an entirely new career and a new family. She took her skills as a writer in the medical field and applied them toward her new two-wheeled passion. Her first story, a feature on Shayna Texter, appeared in an issue of “Woman Rider”.

She soon joined the staff of sister publication “Thunder Press” and in February 2021 became the managing editor of the American Motorcyclist Association. The first issue of “American Motorcyclist” she worked on featured Malcolm Smith on the cover. He turned 80 on March 9, 2021.

It all happened because she watched a movie. “Bruce had something special,” she says. “He was legendary at what he did. The reason this movie has lived on is because people who watched it get the same feeling I did. Everyone who watches it wants to tell someone else.”

The Influence of “On Any Sunday” is Everywhere

Mike Rinn’s parents took him to the Washington International Motorcycle show in 1971 when he was 14. It was held in two large hotel ballrooms and organizers broke the floorplan up by countries and continents. Rinn spent most of his time near the Husqvarnas and Bultacos. Behind the European bikes display a sign advertised the east coast premiere of “On Any Sunday”. He recalled reading about the movie in “Cycle News”.

“I remember this day so vividly,” he says. “The hype of the movie really hadn’t made it to the east coast yet. I felt lucky that my parents wanted to see it, too, because we had to wait two more hours until the next showing.” With their tickets in hand the Rinns were led behind a black room divider curtain where 20 metal folding chairs were arranged. Rinn said it all seemed very ‘impromptu’ as they could still hear the motorcycle show going on a few feet away.

“When the film started, however, I was unaware of anything but the screen. The movie changed me for the better. It was all I could talk about for weeks. I still watch it several times a year and I queue up the soundtrack often, too.”

William Frederick’s wife bought him some “On Any Sunday” movie posters for Christmas one year and he unexpectedly – almost involuntarily – cried. “It just brings me so many good memories riding with my dad and trying to be like Mert Lawwill,” Frederick says. William started on a 1976 Honda Mini Trail. He still has it on his Eastern Maryland farm and uses it to teach new riders.

“On Any Sunday” influence stories are everywhere. On a buried website from a 2005 memorial event for the movie, Larry Langley of the Orange County Dualies M/C wrote about the time he interviewed Dave Evans, the guy who did the standing wheelie on the trials bike. Evans told Langley about the time he stumbled upon a Doug Domokos show in front of a motorcycle dealership.

Domokos called himself the “Wheelie King” throughout the 1980s and was a staple of the motorsports halftime show. Among other acts, Domokos could ride an entire lap on a supercross track on one wheel. After the show Evans talked with Domokos and learned that it was the trials wheelie scene that “got me excited about doing wheelies!” Domokos told Evans. “I figured if you could do it, so could I.”

Still selling on DVD (even VHS!) and currently streaming on Prime, “On Any Sunday” ranks in the top 50 movies of documentaries sold on Amazon and the top 100 among Sports Movies and TV shows (it’s hard to get too excited about these rankings since several exercise videos made for seniors rank higher, but hey…).

The movie has over 1,000 five-star ratings and 900 global written reviews on Amazon. In a 2004 review, David Carlin wrote “I purchased this because I was already getting into motorcycles and recently purchased a Honda Shadow. The music was a bit outdated but strangely enough, I now hum some of the musical themes from the movie.”

In 2013, “Chilidogpete” said, “The first time I saw this movie was in a theatre. When the movie was over I felt like I was buddies with Mert Lawwill, Malcolm Smith and Steve McQueen. I enjoyed this movie so much that I later purchased a street motorcycle and put 50,000 miles on it in five years.”

In 2007, “Matteo” wrote: “If you’re already a motorcyclist, this movie is guaranteed to make you smile and yearn for a good ride. If you’re not yet a motorcyclist, this movie might just turn you into one. If you ride and this movie isn’t on your video shelf, buy it now so you don’t have to face the embarrassment of telling your riding buddies you don’t know who Harvey Mushman is.”

Discussions about the movie even break out in the most unlikely online venues: the gun community Glock Talk, TDPRI, a page for telecaster guitar aficionados, the Ford Raptor forum and every single niche two-wheel discussion page imaginable (shout out to the 18,000 members of the Yamaha TW200 forum).

“On Any Sunday” is far from the last motorcycle documentary ever made but it’s the one movie that froze time. Because of its influence and success, Mert and Malcolm are forever 29 years old. Malcolm loves to tell the story of the kids who came into his dealership a few years ago and thought he was the grandfather of Malcolm Smith. He looked a lot older than the man they saw in the movie thir father showed them.

Vincent Canby, the movie critic, wrote in his 1971 review that Brown may become the “poet of the sports world”. But he only directed two more movies after “On Any Sunday”: a little known ski film called “The Edge” in 1975 and “Endless Summer 2” in 1994.

In the end, he didn’t write poems for other sports. In our little corner of the world, however, Bruce Brown is our Walt Whitman and we’ll be singing his verses for another 50 years’ worth of Sundays.

Neat, Bruce.

Thanks for reading. If you value these stories, there are two ways to keep them going: buy products straight from the shop shop.wewentfast.com There’s an entire On Any Sunday product line, all officially licensed by Bruce Brown Films.