Part 3: Ricky Carmichael’s agent drops a bomb on Honda

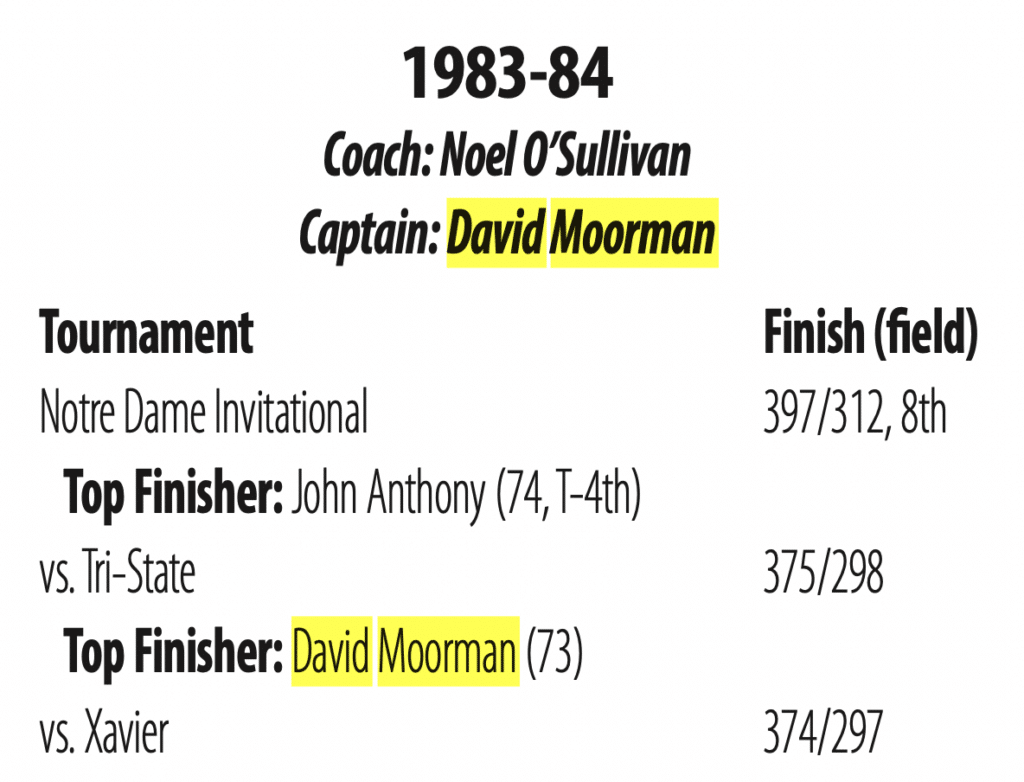

David Moorman was good enough in his youth to attend Notre Dame on a golf scholarship. He graduated in 1984 and in 1987 earned a juris doctorate from the University’s law school. The Muncie, Indiana-born Moorman spent two years practicing law in Texas before he joined Orlando’s Leader Enterprises, an athlete representation firm.

Mentored by legendary sports lawyer Robert Fraley, one of Moorman’s first clients at Leader was Payne Stewart, who won the 1989 PGA Championship. While at Leader, Moorman also represented players in the National Football League and Major League Baseball as well as multiple NFL head coaches, including Joe Gibbs.

Establishing a reputation as a tough negotiator who likes to rethink structure within corporate agreements – a structure that can better serve his clients – Moorman was strictly stick and ball, even after forming his own firm in 1997. His connection to motocross came from mutual friends seeking help.

Grant Waite, a dirt-bike-loving professional golfer linked Moorman to Carmichael through Scott Taylor, who worked with both Oakley and Fox Racing. According to Moorman, Waite asked for a favor; in the fourth quarter of 2001, Carmichael needed help with endorsement contracts. Moorman declined; he was busy and didn’t want to over-commit. In early 2002, both Waite and Taylor got involved and Moorman reluctantly agreed.

In Carmichael, he saw a polite, highly determined and focused young man who kept his life simple and his circle small despite being the undisputed best at what he did. The Carmichael family’s honesty, closeness and clear strategy for success impressed Moorman. As for the contracts, he saw them as a challenge.

“I was drawn to the complexities of RC’s business agreements,” Moorman says in an e-mail. “His sponsor portfolio was pretty strong; however, the contracts were not clearly drafted and many terms (rights of the parties) were in conflict. Sponsors were confused. It was messy.”

He also saw a vastly underpaid athlete. In his opinion, an athlete who was a generational performer, an icon with a sky-high winning percentage, should be compensated accordingly. To Moorman, Carmichael’s compensation structure in many of his sponsorship agreements were lopsided. Too much of the compensation package was tied to performance bonuses.

He viewed Carmichael as being an independent marketing machine that should be paid as such. He didn’t like the piecemeal approach especially adhered to by motorcycle brands–$5,000 here, $50,000 there–for an athlete with such a record. A guaranteed compensation package would benefit both parties; in the case of Carmichael, Honda would be freed from forecasting for race wins and titles and Carmichael gets the lion’s share of the money up front. Plus, there’s the assurance that Honda is truly investing in Carmichael as a marketing partner and helping to build his notoriety and brand.

“We brought a new perspective and approach to deal making and negotiating in motocross,” Moorman says. “Some folks in the industry embraced our approach while others shunned our involvement. We were refreshing to some and others saw us as a menace.” Moorman employed the same philosophy he used in other sports and leagues: high-level performers commanded significant upfront marketing retainers. But Moorman was aware of the corporate philosophies at an OEM such as Honda and how complex and personal the relationships between a rider and manufacturer can be.

[Carmichael] wants a clear mind to focus on the job at hand – preparing for and winning titles – instead of exploring the marketplace for another deal.

David Moorman in a 2003 memo to Honda

On July 18, 2003 – one year and 10 weeks before the end of Carmichael’s original three-year Honda deal, Moorman officially launched negotiations for an extension. He wrote a carefully worded and researched eight-page long memo for four Honda managers who didn’t need a reminder of this rider’s strengths and accomplishments.

The first two and a half pages of the typed, single-spaced document read like an extended trading card. Carmichael’s accolades, right down to winning percentages, were presented in great detail within an alphanumeric outline. In the middle of page three Moorman explained exactly why he was seeking a unique compensation structure, with no performance bonuses at all, unheard of in the sport then, and still today.

“We believe Ricky deserves to be paid as a champion,” Moorman wrote. The proposal then reiterated that Honda paid Carmichael an approximate total of $4,500,000 in 2002 and was well on its way to a similar amount in 2003. “Thus, from an empirical standpoint, we have determined Ricky’s future fair market value to be consistent with the money he has actually earned and received from Honda in the past…

“[Carmichael] wants a clear mind to focus on the job at hand – preparing for and winning titles – instead of exploring the marketplace for another deal.”

Moorman ended the defense section of his proposal with a request and offer to make his client more of a partner in licensing and team sponsorship activities, such as involvement in other Honda divisions. He then outlined term and territory, services, and compensation of the proposal.

He asked for the new contract to begin on October 1, 2003 and end on September 30, 2006, with a year four option based on performance. The ‘let’s get-to-the-bottom-line-number’ fell to the top of page seven under section III. Compensation:

A. Marketing Retainer: In consideration of the above-stated services, Honda shall pay Carmichael the following guaranteed marketing fees:

1. Contract Year One: $4,500,000 (Payable in twelve (12) equal monthly installments).

The ask for contract years two and three increased to $4,600,000 and $4,700,00, respectively. Under B. Performance Bonuses and C. Team Sponsors Compensation was the word “NONE”, meaning Carmichael waived the option of extra money for winning races and championships. Licensing and merchandising were proposed to be handled on a case-by-case basis.

Carmichael made it clear that he wanted to stay at Honda and says he knew Moorman was working on his behalf and in his best interests but didn’t get caught up in mulling over salaries, bonuses or guaranteed compensation; he was too focused on racing and winning. “It was kind of in one ear and out the other,” he says.

Moorman stays behind the scenes. He didn’t attend races but he closed the memo with expectations of meeting in person to negotiate further and said his client was prepared to finalize the deal by the end of August, 2003. Moorman faxed the memo to Gary Christopher, Ray Blank, Chuck Miller and Erik Kehoe, the motocross race team manager.

Then they waited.

When told about the letter, one former agent, who represented elite level riders of the era, and spoke on the condition of anonymity, said…

Don’t make the mistake of telling Honda how important you are. Honda never allowed an athlete to become bigger than the brand.

Moorman says negotiating a contract extension that early was not all about the money. He knew he was working around a long-standing, rigid business culture and process. But he also believed deeply in his client. “If there was ever anyone in motocross who deserved guaranteed compensation it was RC,” he says today. “I felt justified and confident to argue for the same.”

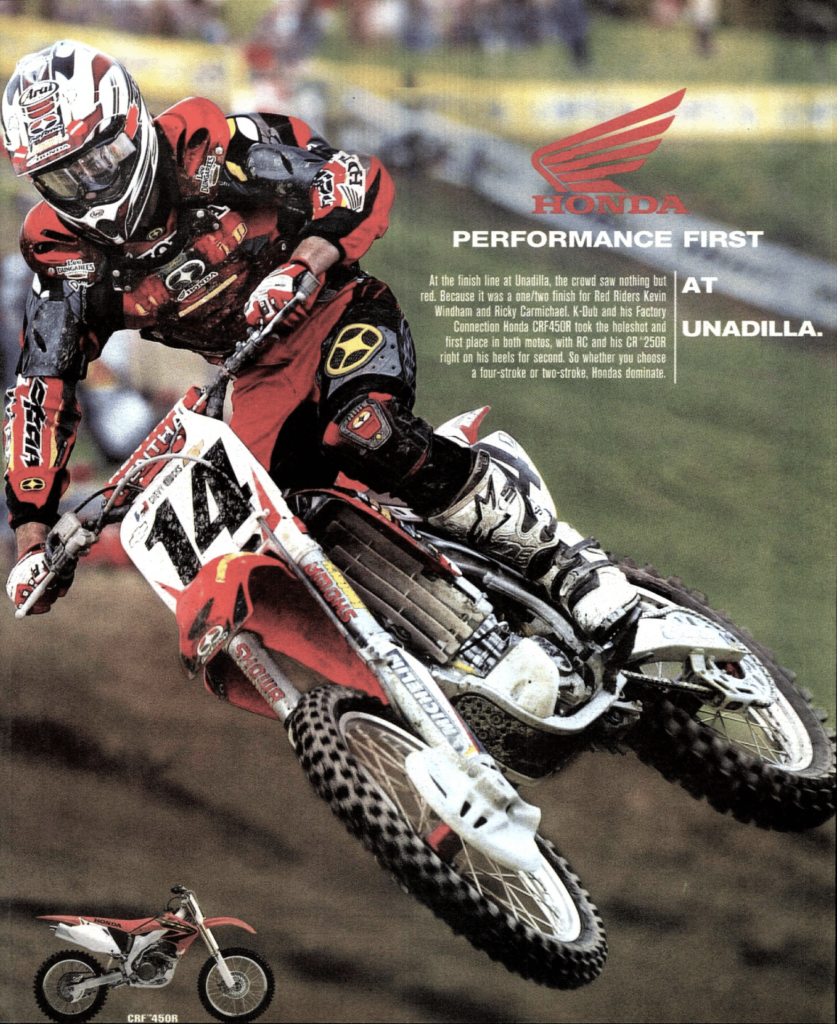

What happened next is likely irrelevant to the negotiations but still an interesting coincidence; two days after the memo coughed out of a fax machine in Torrance, Calif., Carmichael lined up at Unadilla Valley Sports Center where he attempted to win his 22nd consecutive Pro Motocross. Instead, Kevin Windham handed him his first loss in 103 weeks. Windham rode a Honda CRF450R, the first AMA Pro Motocross win for the four stroke, which debuted over two years earlier.

One week later, Windham went to Washougal and did it again, handing Carmichael four consecutive moto losses for the first time since June 2000. Despite finishing second in all four motos and maintaining control of the championship, Carmichael still felt furious and frustrated. Honda’s crew chief, Cliff White, knew exactly what to say. He had navigated the egos of two elite-level Honda riders battling for wins many times in his long career.

“There’s no way you could have ridden that two-stroke any faster,” Carmichael says White told him after Unadilla. “He beat you because he was on a faster bike. Don’t beat yourself up.”

Within weeks, Carmichael had a stock CRF450R in his garage.